Women have always demonstrated capabilities of exerting powerful influence in the world. Undoubtedly, the Nineteenth Century provides a glorious example of what women can do: in this era, feminism gave birth to the Suffragette movement in England and France, gathering a whole gender in a fight against that patriarchal society which was meant to end once and for all.

Despite the examples of courage and devotion left by the Suffragettes, the role of women has somehow taken a step back due to the creation of those stereotypes that gravitate around the idea that they are the weak gender. Meanwhile, with the arrival of the modern era, the world had to face new challenges related to new security issues; among the most remarkable examples, the terrorist threat. In few years, and with greater emphasis after the 9/11 tragic events, terrorism has adopted different facets that required higher attention from the counter-terrorism field. Among these, the role of women. Mindful of the lessons from the past mentioned above, it is necessary to be aware of the strong influence that women may exert not only in relation to morally-respectable causes, but also to all those terrorist organizations that occupy different areas of the world and constitute a serious threat to societies.

Specifically, it is vital to forget the idea that women are merely victims and start considering the numerous and most diverse motivations that they may have when joining a terrorist organization. The reason for posing this question comes from the need for establishing gender perspectives in counter terrorist actions, allowing to cover a broader area of research.

Why do women join terrorist organizations?

The misconception that women are linked to terrorist for their sole role of “brides or wives for fighters” is nothing more than wrong. Surely, love can be a push factor, but it is hard to think that the eight hundred women who are believed to have travelled abroad to join ISIL were only driven by love. Therefore, to what extent are women tied to political matters? How much are they influenced by men?

The second most stereotyped reason to justify women joining terrorist organizations refers to brainwashing. With this regard, it is worth mentioning a recent study that has refuted the hypothesis that radicalization is the result of psychological illnesses and mental disorders. On the contrary, it can be pushed by social conditions, feelings of alienation and loneliness, which are highly common among women, especially in young ages. In fact, there is a surprisingly high number of women who have been raped and/or subject to violence; feelings of hate and grievance, if coupled with wrong contacts made for example on social media, may result in the decision of flying away and radically change one’s life.

Why do terrorist organizations rely on women?

As a matter of fact, once discarded the idea of brainwashing, terrorist organizations may appear attracting to women under different circumstances (e.g. financial benefits, powerful roles, protection). Indeed, there have been numerous cases of women who left countries such as the United Kingdom or Belgium to join ISIL in a fight they thought they belonged to; some of them claimed how easy their life would be under the protection of a man – for example they would not need to stay in the educational system anymore, given that their role would be limited to being housewives. Some others had political reasons and claimed they would be treated differently if ever caught by governments – receiving a less tough penalty and treatment, although there is no evidence this would be true.

Above all, there is still very little evidence on the subject, especially because it is highly underestimated. Nevertheless, research needs to be implemented both on female and male perspectives.

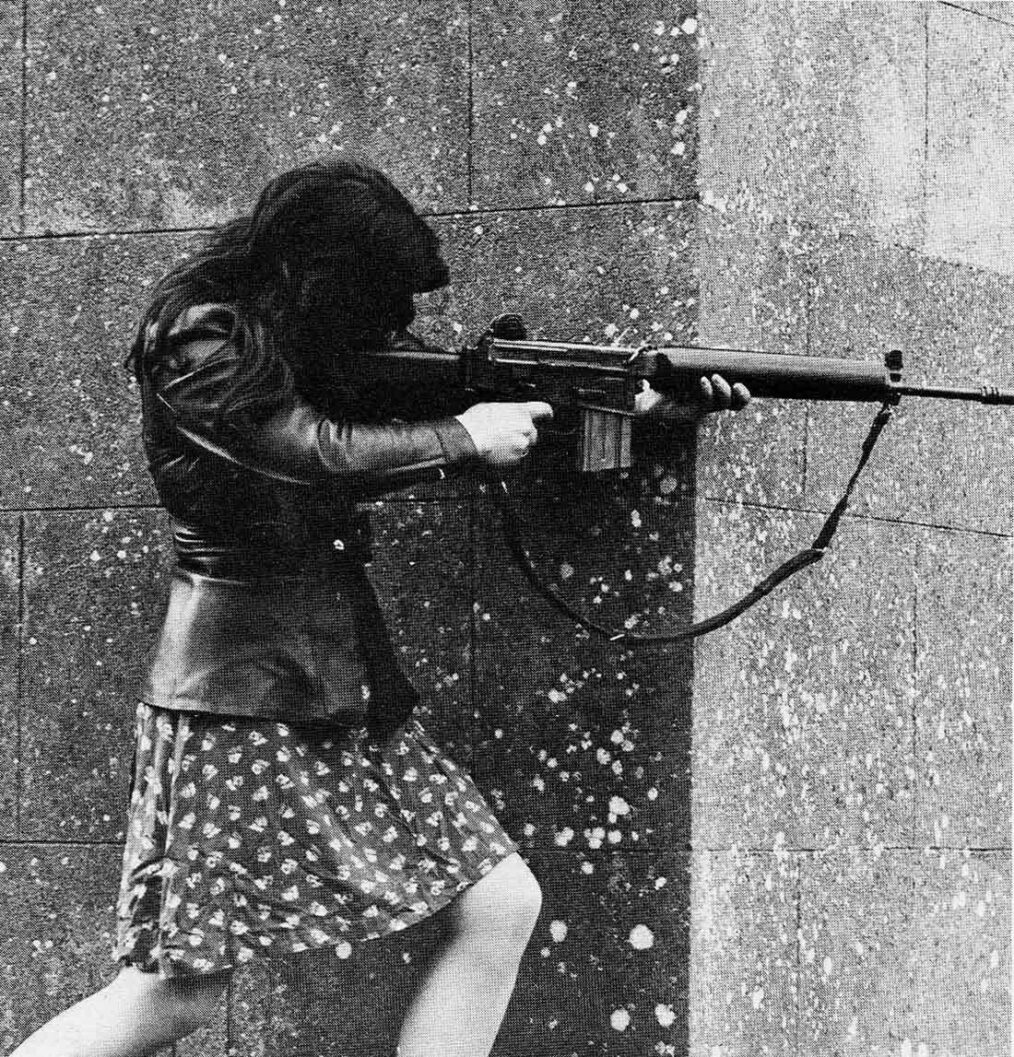

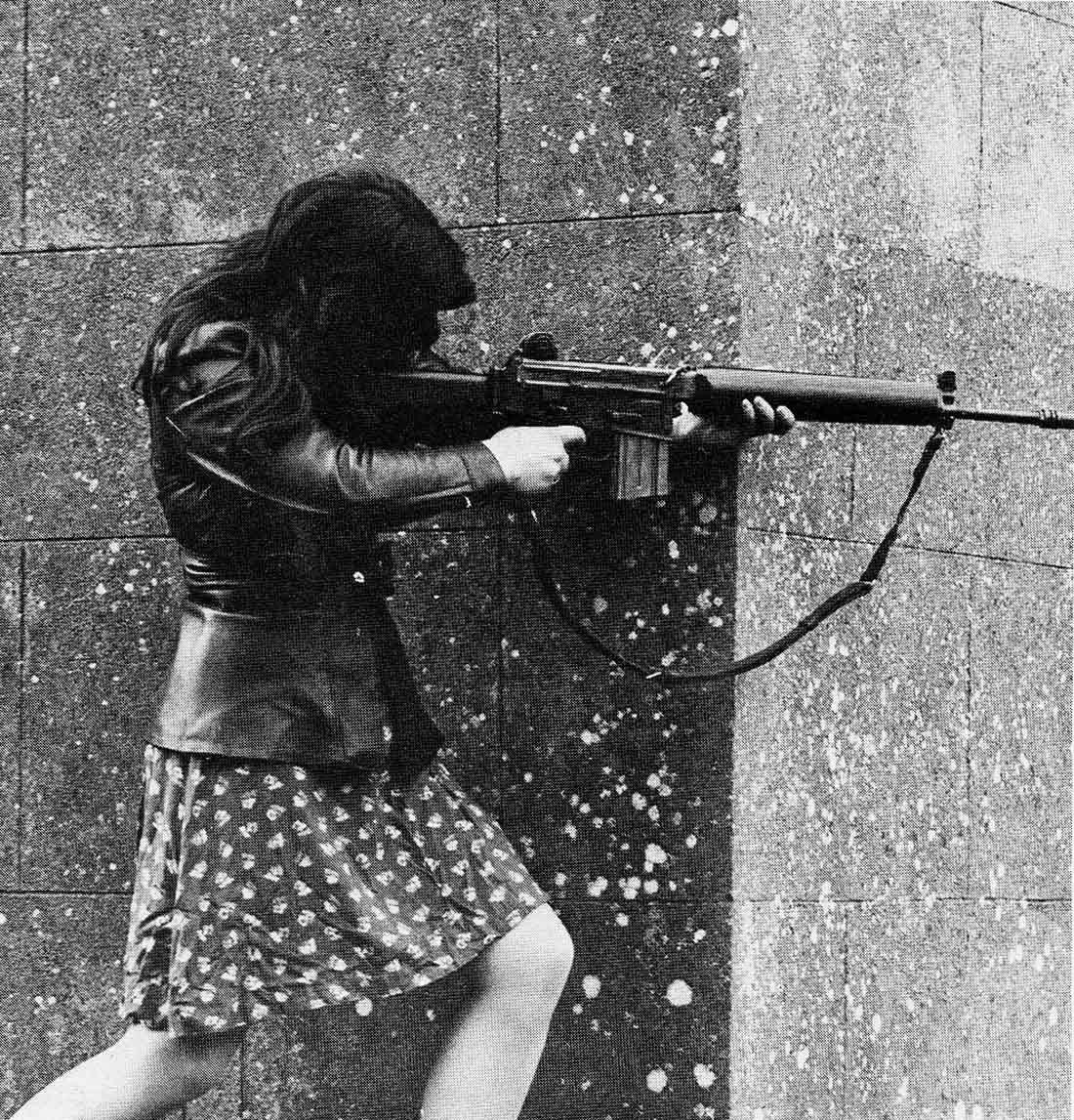

As far as women are concerned, it is important to keep in mind the distinction between women who support terrorism and extremist beliefs and women who join terrorist organizations. The two categories need different levels of analysis and attention: while the former necessitates greater education and support, focused on the risks that the involvement in terrorist activities may cause, the latter needs a proper intervention and eventually forms of rehabilitation into the society as part of de-radicalization missions. Furthermore, it is also necessary to consider that women may also be found in the front line as well as men; Atran (2003) provides an interesting analysis on the role of suicide bombers, considering both men and women and the increasing in the presence of the latter in the past few years.

It is imperative to understand and detect the reasons behind choices of radicalization in order to be able to spot any sign of alarm in our society, always while taking into account that female involvement in terrorist activities is not always driven by ideological concerns.

However, it is not necessarily a matter of punishment, but of providing education and support to vulnerable women that may be targeted and recruited. With this in mind, direct witnesses from women involved in terrorist-related actions should be collected to build up a correct analysis on the motivations behind the choice of joining a terrorist organization and therefore counter the threat from its origins.