As a part of The Women in Extremism Program, Rise to Peace’s Simone Matassa had the privilege of interviewing Phil Gurski to talk all matters of female terrorism. Phil Gurski, who is the President/CEO of Borealis Threat and Risk Consulting, has over 30 years experience as a strategic intelligence analyst specializing in radicalization and homegrown Islamist extremism with the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), Communications Security Establishment (CSE), Public Safety Canada, and the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP). The interview with Phil focused on the gender side of radicalization, female motivations for extremism, and women’s role in counter-terrorism initiatives.

What gender differences are present in radicalization processes and what do you think are the main differences between how women are radicalized compared to men?

Phil Gurski: I think the answer to this question is that there are a lot of unfortunate stereotypical myths that there are significant differences, and hence that women either have to be treated differently or [and this is more important and more dangerous] that somehow women’s roles are minor and not as serious. And, therefore, in instances where women have traveled to join terrorist groups that we tend to think it’s not nearly as serious and tends to treat them with kid gloves.

We certainly saw that especially with Islamic State, where a lot of women played that card and claimed they were coerced by their male companions and actually had no real part in terrorist activity – that they took more of a background-position. I think this myth has had an effect on how people look at female terrorists [female jihadis]. Agency is the key issue here as there has been this unfortunate assumption that women don’t have agency and have somehow been forced or duped.

People often assume that Muslim women don’t have choices, as it’s a male-dominated faith, and that the women actually never agreed to do anything and were actually just following their husbands. The cases I was involved with women were very much as devoted to the cause as their husbands, brothers, boyfriends, etc. so I think we have to be very suspicious when women try to deny they had any role to play and that they were somehow innocent victims of a terrorist movement. From that perspective, the penalties and approaches should be the same – I don’t see a gender distinction.

Do you think gender roles play a big part in how women are viewed in terrorism? Are women just as equally capable of carrying out terrorist attacks compared to men or do gender roles prohibit them?

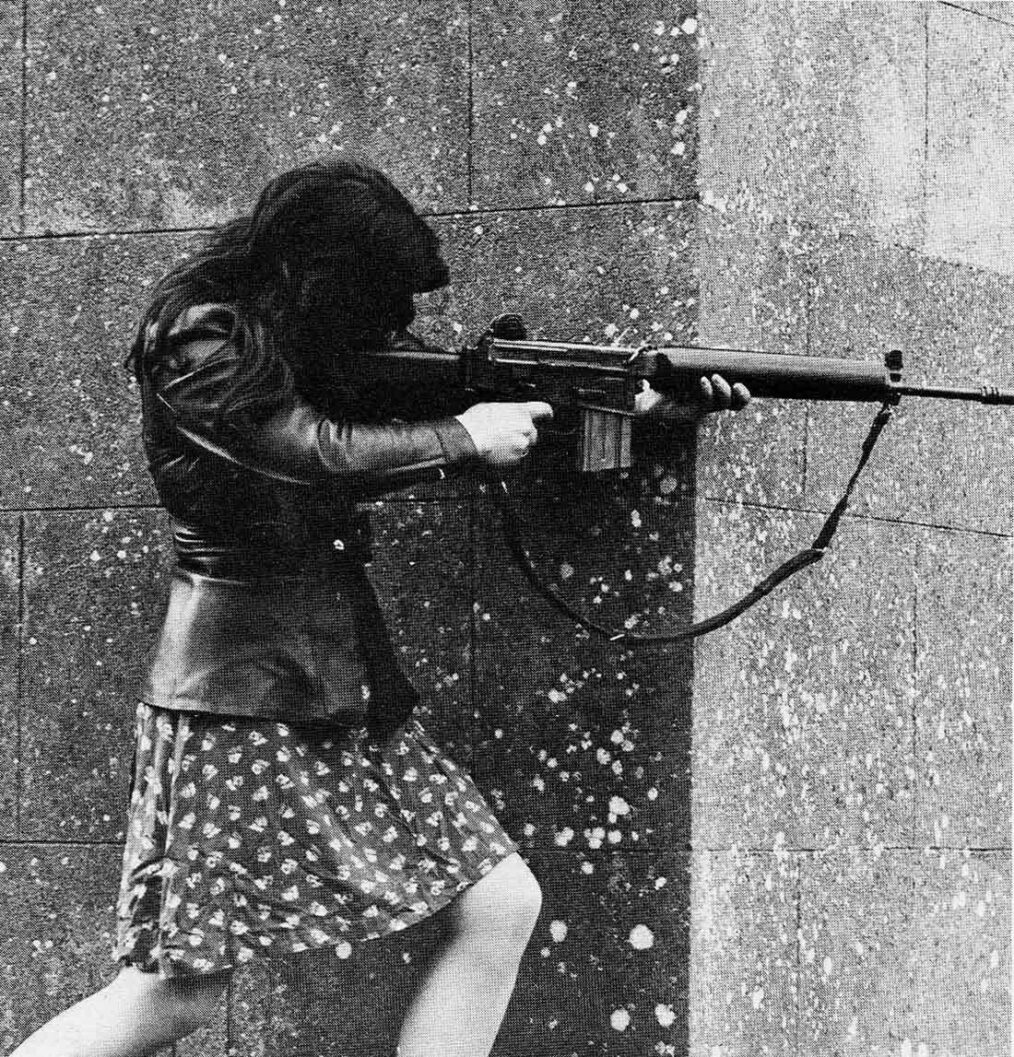

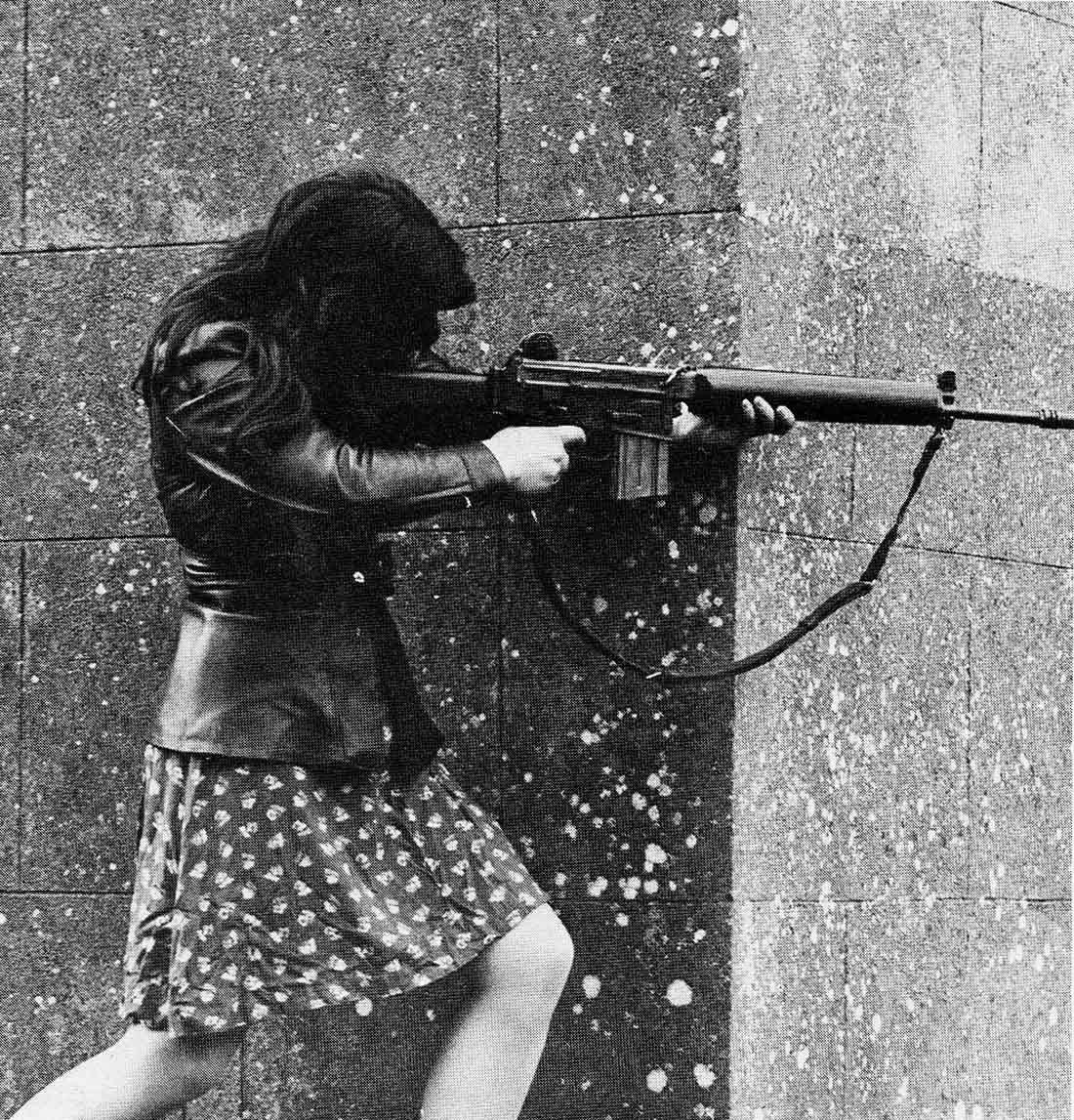

Phil Gurski: Historically, women played incredibly important roles in terrorist groups i.e. IRA, Baader–Meinhof in Germany, LTTE in Sri Lanka. So there is no question that women have and are capable of carrying out active roles in terrorist groups up to and including carrying out attacks and killing themselves in suicide attacks. When looking at Jihadis early on, there certainly was a gender division within most groups which saw women as the support role.

Leaders such as Bin Laden and Al-Zawahiri would say this. They would say we welcome our female members, but this is very much a man’s job. Then Islamic State came along and really reversed the paradigm. They very much stated that isn’t actually true; women are capable of carrying out activities on our behalf and this is – I think – why you probably saw a larger percentage of women actively going to join Islamic State with or without partners.

We had a famous case in Canada in 2015 where three young women in high school sought to join the Islamic State and got as far as Cairo before they were turned back by authorities. But this was completely on their own accord. I do not think that there is inherently a different role or paradigm for women terrorists. There may be some physical differences in strength etc. but when we try to maintain this while saying women are the weaker sex, we do a disservice to women who are terrorists and I think we also underestimate the role they can play.

What are women’s motivations for joining a terrorist organization- do they differ from that of a man joining a terrorist group?

Phil Gurski: I do believe they are one and the same. Using the Islamic State as an example: the Islamic State was remarkably successful in doing a couple of things. First of all, establishing the Caliphate as the ideal Islamic homeland that had appeal for an awful lot of people.

I know from the investigations we carried out people would talk about this; that they finally have a real Islamic State where Islamic law will be practiced and everything would be great. Secondly, they appealed to people to help build this State. And thirdly, they were very successful in pointing out atrocities that true Muslims have to reverse, whether these were atrocities carried out by the West or carried out by dictatorships.

This appealed to any believing Muslim who wanted to make a difference, so I think the motivation would be the same for both men and women. There is also a sense of adventure and an intense hatred for the societies in which they live. We saw a lot of people turn their backs on Western society saying they can’t live in this apostate regime anymore and that they have to go to where Islam is being practiced. I definitely saw this as much with the women as I did the men, so I would say there is not a major distinction between the motivations as to why either gender would choose to join a terrorist group.

What part can women play in countering terrorism and preventing the processes of radicalization?

Phil Gurski: The fact that more women have joined terrorist groups means you have more women coming back, and women who have abandoned the cause and can talk about the experience in the sense that it wasn’t what they originally thought. A small percentage of those women want to go public, but the vast majority want to leave it behind them due to the repercussions.

I think there is room for women who do come back to say here is what I saw, here is what I believe to be the case, and here is how it proved to be a complete lie. I think they can play the same role as former men could, I don’t see any difference in that respect given the fact we are seeing more of them they could maybe appeal to a different audience then the men could. We are in a time now where we have greater numbers than we have had historically in terms of women who have gone to fight or gone to support Islamic State as members and have got out. But I do think women could have something to say especially to children – kind of like the scared straight programs in prisons where they basically use their own experience to show others that it’s not worth it.

Conclusion

What can be taken from this interview with Phil Gurski is that there is an undeniable relationship between gender and extremism that is largely unexplored. While current societal stereotypes halter women’s roles in terrorism, there is still a need to be vigilant while looking at the female side of extremism.

As Phil alluded, when people underestimate the power and role of women, it becomes dangerous and creates an environment where women can go unnoticed for their violent actions.

More research and demonstratable interest in female extremists is needed to pave the way to preventative measures in helping tackle the gender issues in terrorism and to shaping policy in how female extremists are prosecuted.

View the full interview below:

Simone Matassa, a counter-terrorism writer and Head of the Women in Extremism Program at Rise to Peace.