In relation to terrorism, domestic intelligence collection is relatively limited in scope due an absence of an agency or structure dedicated solely to domestic intelligence collection. While the FBI and other federal law enforcement agencies participate in intelligence collection and analysis within the United States, it is largely case-based and limited to involved parties. To be clear, domestic intelligence collection does not include subjects discovered communicating with foreign nationals (in those cases, there is a structure to go through with FISA courts that will lead to further intelligence collection and analysis.)

A collaborative effort between non-government parties could address many of the issues found in using government entities to conduct domestic intelligence operations. Such an approach has a proven track record of success, as there is a long history of private companies being tasked with intelligence operations, even domestically, dating back to the very beginning of the United States.

There have been attempts to address flaws in intelligence collection and dissemination by the federal government. Notably, the establishment of Fusion Centers and Joint Terrorism Task Forces was intended to bridge the disconnect between federal law enforcement, the private sector, and state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies. These groups have had debatable success, and there are many reports that private sector involvement in these groups is limited.

The objectives of domestic counter-terrorism intelligence collection are broad and seek to acquire data on a variety of activities, including:

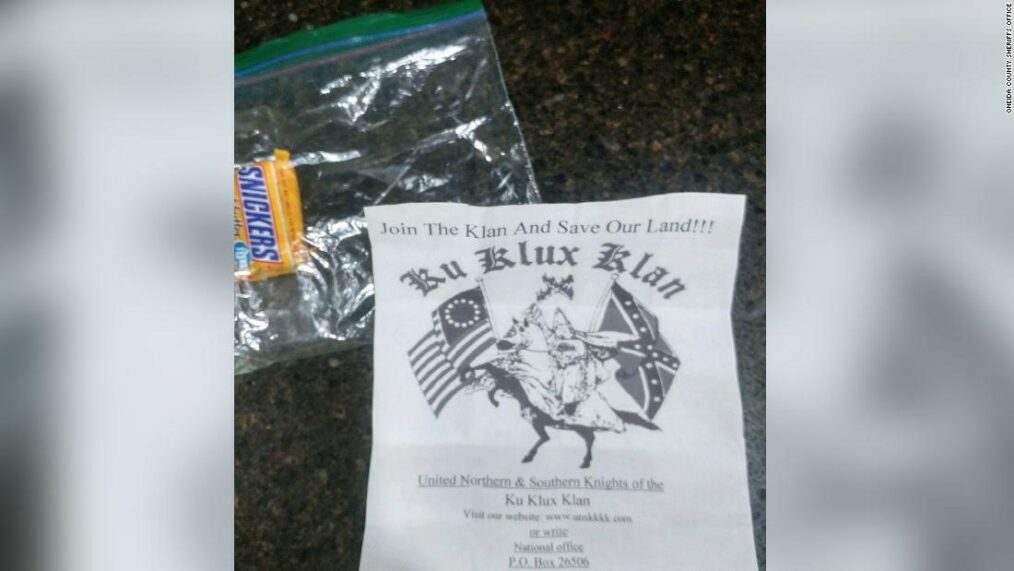

- Recruiting to extremist ideologies and groups

- Acquiring funds and logistics

- Training for terror operations

- Detecting surveillance and reconnaissance

- Planning of terror operations

Limiting the collection process to government entities, which have limited resources and limited scope of capabilities in domestic intelligence, leaves substantial gaps in which crucial intelligence may be missed. Indeed, there are several private intelligence companies as well as private research entities, such as the Southern Poverty Law Center, that provide a significant amount of data on terrorism and extremism in the United States.

Another key area in which collaboration should be made is the inclusion of subject matter experts involved in numerous areas of American critical infrastructure, of which the vast majority is controlled and operated daily by the private sector.

However, when these groups work individually and do not cooperate, they often fail to close many of the gaps which exist in domestic intelligence.

This large pool of individuals and groups, ranging from non-profits to academic institutions, have created arguably the largest store of knowledge on counter-terrorism and counter-extremism- and yet it is not being fully utilized.

Establishing collaborative groups that unite academics, private companies, non-profits, and researchers could address the ‘explorative’ component of domestic intelligence collection and analysis. This element of intelligence seeks to develop more broad understandings of the threat picture facing the homeland, as well as collect data on individuals and groups involved in extremist ideologies which may lead to operational violence. Utilizing non-government entities to conduct intelligence could bring the technical strengths of the private sector, including innovation strengths and technology, to the forefront of the fight against terror.

The collaborative effort mentioned throughout this writing would work most effectively in collection and analysis of the vast open source data available, which comprises nearly 80% of useful intelligence. While there are brief collaborative efforts on research, the collaboration often occurs on specific, case-sensitive research studies about a specific topic- not long-term collaborations.

How can non-governmental entities be brought together to produce a unified intelligence product? A plausible strategy would be to first hold a conference or a series of conferences to bring together representatives of respected organizations from the disciplines discussed above, conducting meetings about logistical options for such a collaboration. An academic institution may be the strongest location to physically host such a collaboration due to its facilities, space, and readily accessible traditional sources of data. Furthermore, a strong online network in which research can be shared and collaboratively worked on with a clear system of dissemination must be established. All of this would develop a relatively substantial cost, however, and perhaps partial government funding would produce sufficient impetus to begin work on such a project.