The latest talks between the United States and the Taliban may conclude with a deal. Content of the peace agreement has been finalized in Doha, according to former Afghan ambassador to Pakistan Omar Zakhilwal. Sources indicate the Taliban agreed to a reduction in violence and potential talks with Afghan government if the deal is sealed.

The agreement revives hopes for a long-term solution in Afghanistan’s painful 18 years of war. However, the potential deal must be treated with caution if US negotiators do not look beyond the peace agreement.

The US-Taliban negotiations have been marked by an on and off pattern of violence. In August 2019, the US and the Taliban concluded the 9th round of direct talks and were on the verge of reaching a deal that could allow the pullout of foreign forces from Afghanistan and a ceasefire that would put an end to violence. However, in September the Taliban conducted an attack that killed one US soldier and 11 civilians in Kabul. President Trump responded by calling off a scheduled meeting with the Taliban and abruptly halted the peace efforts for over three months. At the end of November, the US president made an unannounced visit to Afghanistan, met Afghan president Ashraf Ghani, and declared he revived the paralyzed peace talks. Yet, an alleged US-Taliban prisoner swap failed, and the ‘trust building’ exercise between the parties seemed to also be overwhelmingly weakened.

According to Trump, the Taliban strategy has been to better their leverage in the peace talks through terrorism. On December 11, the Taliban staged an attack on the Bagram military base. An explosive-laden vehicle went off in the vicinity of the airbase and was followed by shooting. One day after, US Special Envoy to Afghanistan Zalmay Khalilzad announced a ‘brief pause’ in the already intermittent peace talks. Two more US soldiers were killed by Taliban in January, reaching a total of 2,400 U.S. troops killed in the US’s longest war. The US-backed government forces also stroke back through artillery and aerial attacks that killed over 20 Taliban.

Given that both parties have been focused on maintaining power positions during the negotiations, the content of the agreement might be less of a breakthrough than expected. The US approach to negotiations with the Taliban has been modelled on a straight forward logic: if you have more power than the counterparty, you win, otherwise, you lose. The Taliban, on the other hand, have been capitalizing on a different kind of power – that of field knowledge and terror. However, the release of the ‘Afghanistan Papers’ by the Washington Post has confirmed it is unclear what ‘winning’ means for the US, as there is little consensus among US leadership on the war’s objectives or about how to end the conflict.

Recent developments show talks lost sight of what are the best potential results of a US-Taliban peace agreement. Taliban’s spokesman Suhaln Shaheen declared that “there had been no discussion on cease-fire since the beginning, but the US proposed reduction in violence.” Whereas US officials praise the Taliban’s decision to accept a violence reduction plan, Afghan government officials are rather concerned: a ‘reduction of violence’ plan does not contribute anything beneficial to the peace process, said Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah. Salam Rahimi, the state minister for peace affairs, called the plan ‘unacceptable’.

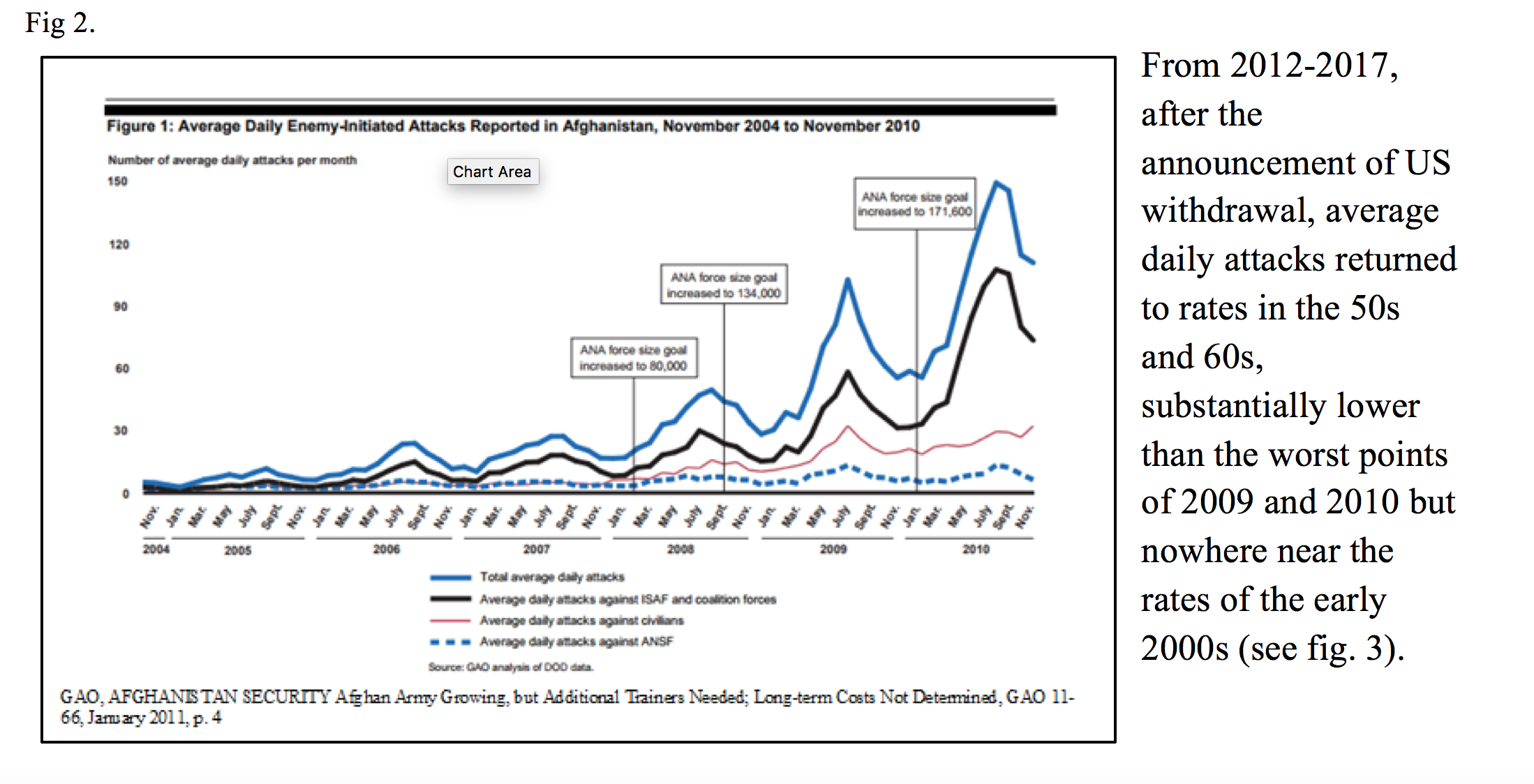

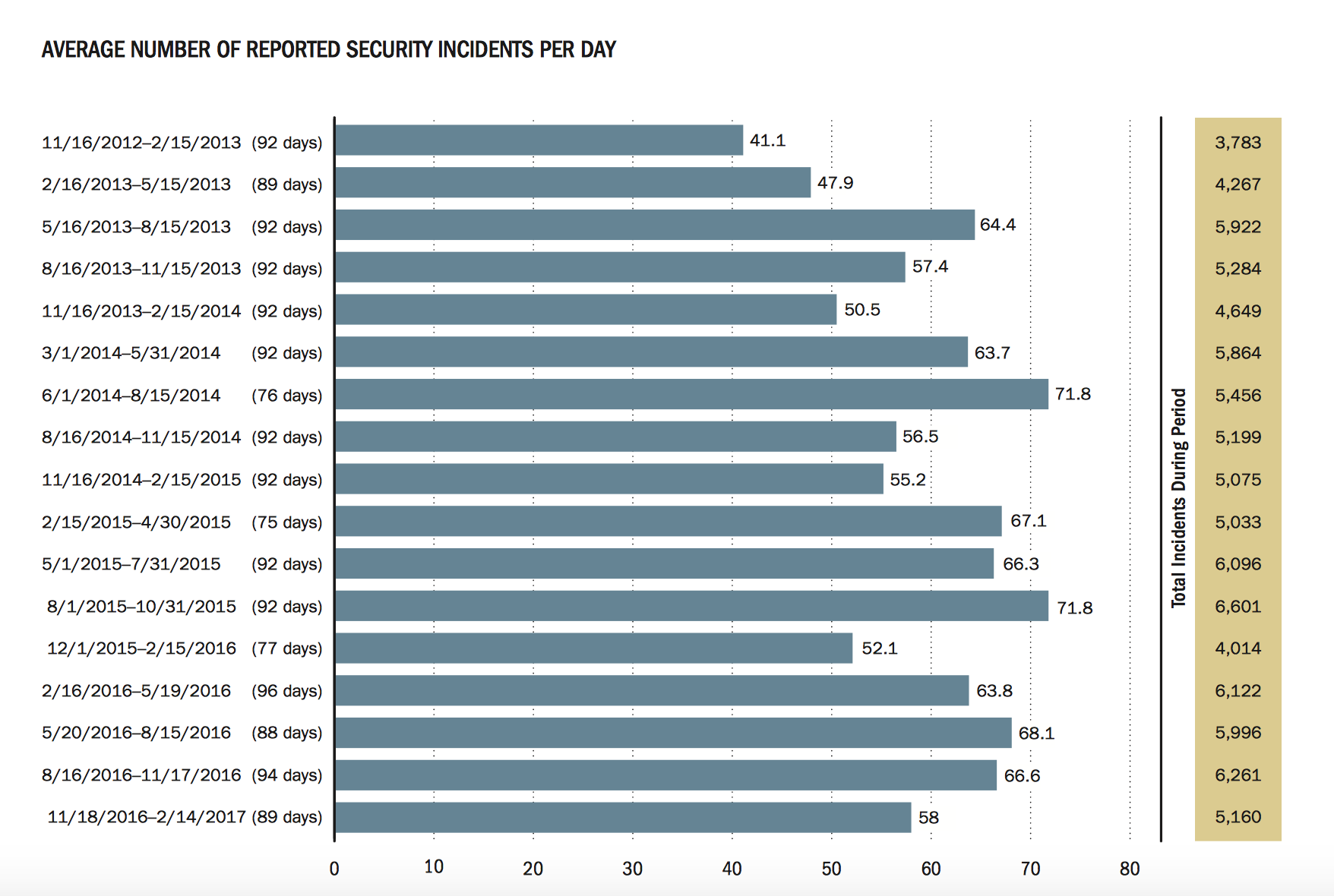

The past months show no indication that an agreement will automatically lead to de-escalation. Peace processes often imply strategic and tactical deception and the second half of 2019 witnessed violence escalation. The number of high-profile Taliban attacks increased, indicating that actors willing to negotiate and eventually sign peace agreements may engage in violence in order to undermine their new partners.

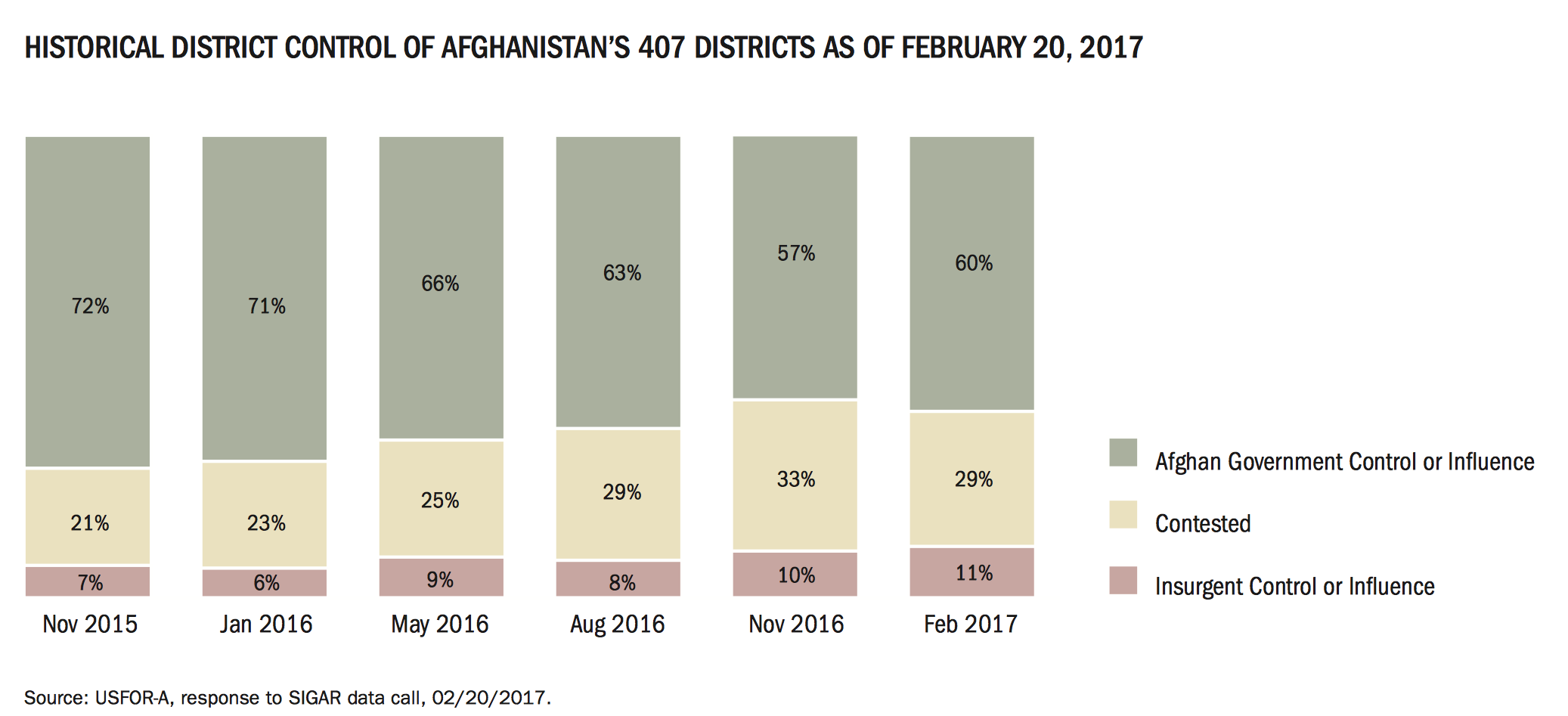

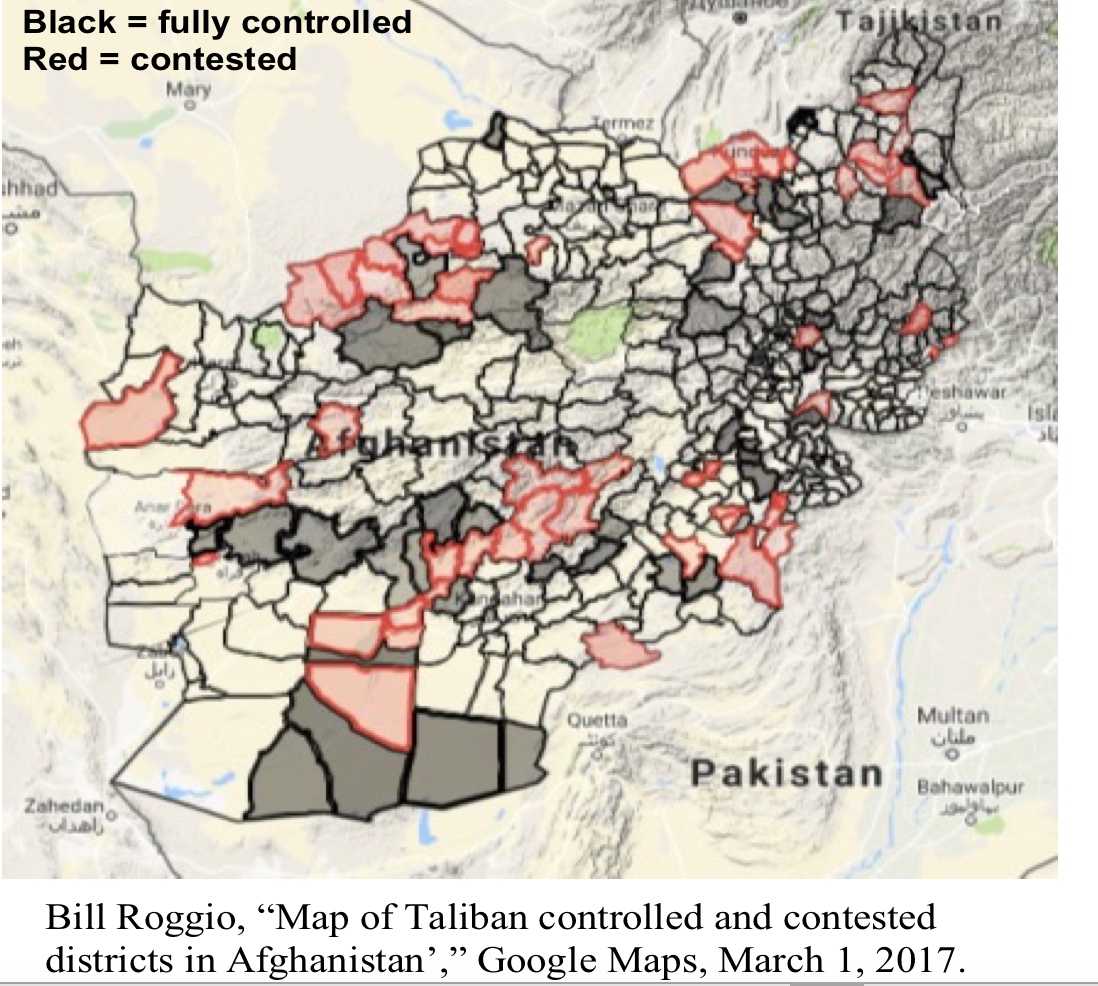

Although both the Taliban and the US seem to have a common goal — the withdrawal of the US troops from Afghanistan — on the short term its materialization remains unlikely. In practice, the US will not withdraw all its troops from Afghanistan, and nor will the Taliban stop engaging in violence. Even if the deal is signed, it is unlikely the Taliban would implement a ceasefire, given the fragmentation and lack of discipline within the organization.

Although a potential agreement between the parties revives hopes for a solution in Afghanistan, positive scenarios are likely only if the US looks beyond the current deal during negotiations. A deal between the US and the Taliban is the beginning of a long term peace process, and has little value for the future of Afghanistan unless a clear action plan for the aftermath of the agreement is formulated. The United States must formulate recommendations and contribute to the negotiations and reconstruction efforts that will follow a deal with the Taliban.

A comprehensive plan for addressing the domestic conflict is necessary. The conflict has a strong domestic component that goes beyond the US-Taliban conflict. The Afghani Constitution mentions 14 ethnic groups, and the country is subject of a fragile balance. Sustainable bridges must be built for further negotiations between the Taliban and the Afghan government, as the former refused repeatedly to negotiate with Afghan officials because they are part of a “puppet government”. Furthermore, the withdrawal of US troops without a plan for security provision may witness an increase in intra-state conflicts. The power vacuum left behind may benefit not only the Taliban, but any of the 22 terrorist organization currently operating in Afghanistan.

The regional component of the conflict in Afghanistan further complicates resolution and should also be addressed. Pakistan warned thhat tensions in the Middle East following the killing of Iran’s Al-Quds Force Commander Qasem Soleimani could hit the reconciliation process in Afghanistan: “On the one hand, we have historical and brotherly relations with Iran, while on the other, our millions of people are working in the Gulf States. We have to be very careful. We have to maintain a balance to protect our own interests” said Pakistani Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi.

Regardless of a potential conclusion of peace talks between the US and the Taliban, observers must remain cautiously optimistic. The potential agreement might be less of a breakthrough than it seems, and the cycle of violence is unlikely to be broken unless a long term plan for the future of Afghanistan is in sight.

Elisabeta is a Counter-Terrorism Research Fellow at Rise to Peace. She is also a Ph.D. candidate in Public Policy at Central European University in Budapest and Vienna.