For some time, President Trump sought an opportunity to withdraw United States troops from northeastern Syria. He considers regional security issues to be the responsibility of local actors, and thus no longer saw any purpose to remain after the defeat of Daesh.

Trump began the extraction of an estimated 100 to 150 military personnel from the 1,000 US troops stationed in the area despite the perception that this decision could leave the region vulnerable.

The withdrawal of troops provides a little motive for the US to continue its alliance with the People’s Protection Units (YPG). These Syrian Kurdish Forces —along with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) — have been instrumental in the fight against Daesh. With the US abandoning them, it gave Turkey the green light to enter Syria.

Why is Turkey moving into Syria?

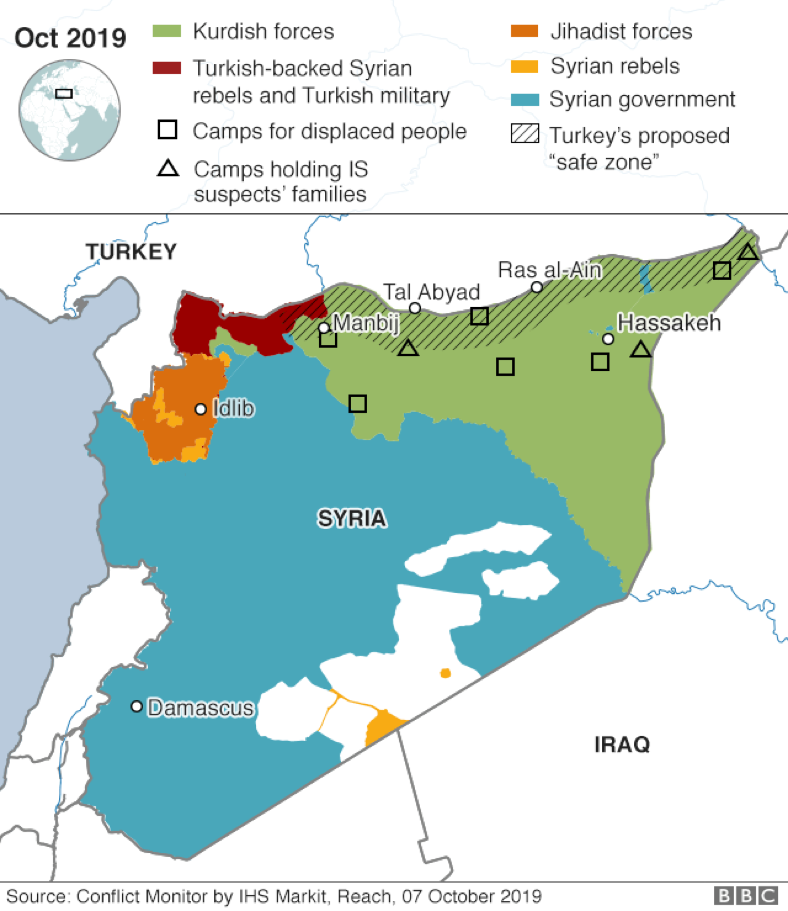

Only days after President Trump ordered the retreat, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan commenced a ground offensive. The intent of the operation is to clear the Kurdish militias holding the territory in northern Syria. Erdogan planned this action for the last two years, with the end goal of a designated “safe zone” to house at least 2 of the 3.6 million Syrian refugees living on Turkish soil.

Nonetheless, the Kurds explain that Turkey’s actions are risking all the gains made against Daesh. For example, the Kurdish forces have thousands of Daesh prisoners, including fighters and their families, under their control. If a conflict occurs, it is unclear if they will have to withdraw to battle the Turkish forces. The prisoners could escape, and liberated cities could fall back to Daesh.

The green area on the map is the “safe zone” that Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is attempting to create.

What does this mean for the region’s stability?

Trump’s decision and Turkey’s subsequent assault could result in dire consequences to regional stability. The reemergence of Daesh remains a significant security threat in the wake of this offensive. As SDF deploys forces into northern Syria to battle Turkey, this will leave other parts of the country vulnerable. In recent months, there have already been instances of erratic attacks from the Daesh prison cells as well as tensions rising between the SDF and local Arab tribes.

According to the SDF, there are over 12,000 suspected Daesh members housed across seven prisons, with at the very least 4,000 of them being foreign nationals. These prisons are scattered across the country, but at least two camps — Roj and Ain Issa — are located inside the “safe zone.”

According to the White House, these camps will become Turkey’s responsibility; however, chances of a smooth handover from Kurdish forces to Turkey are unlikely. This situation could potentially lead to hundreds of escapes of alleged Daesh fighters and sympathizers.

Another possibility is an increase of Russian influence in the region, and consequently, the consolidation of the Assad regime. The United States will renounce an essential aspect of its sway in Syria without receiving any concessions in return from the government. Therefore, Russia will be able to extend its influence over Syria’s future.

It is likely that the Kremlin will forge a closer relationship with the SDF, as they search for new allies during the conflict. Damascus could spread its jurisdiction over Syria’s territory and potentially increase control over the country’s oil fields as well as other crucial economic resources.

Finally, the humanitarian aspect of the Turkish operation will likely be catastrophic. The United Nations claims that many of the 758,000 residents along the Syrian border were displaced at least once from conflict. Further action from Turkey could only exacerbate the situation.

It can cause civilians to seek refuge in Arab-majority areas south of the border, or in Iraq, which is currently undergoing violent protests throughout the nation. Also, Erdogan’s plan to relocate over a million Syrian refugees to the “safe zone” could cause further instability by dramatically changing the ethnic composition of the region.

Overall, the decision to withdraw troops from northern Syria based on an erroneous assumption that the Islamic State has been wholly eradicated may only fuel the group’s resurgence. There are already signs of Daesh regrouping, with no changes to its ideology, and with most of its operating structure intact. Therefore, US troops leaving the region will only lead to them reemerging as a threat.

For this reason, Group of Seven (G7) countries must attempt to shift Erdogan’s advances through economic means or political pressure to avoid further instability in the region. Also, for the US to continue to have reliable allies along with some influence over the Middle East, they must not abandon the YPG by withdrawing all troops from northern Syria.