What Does the Future Look Like for ISIS?

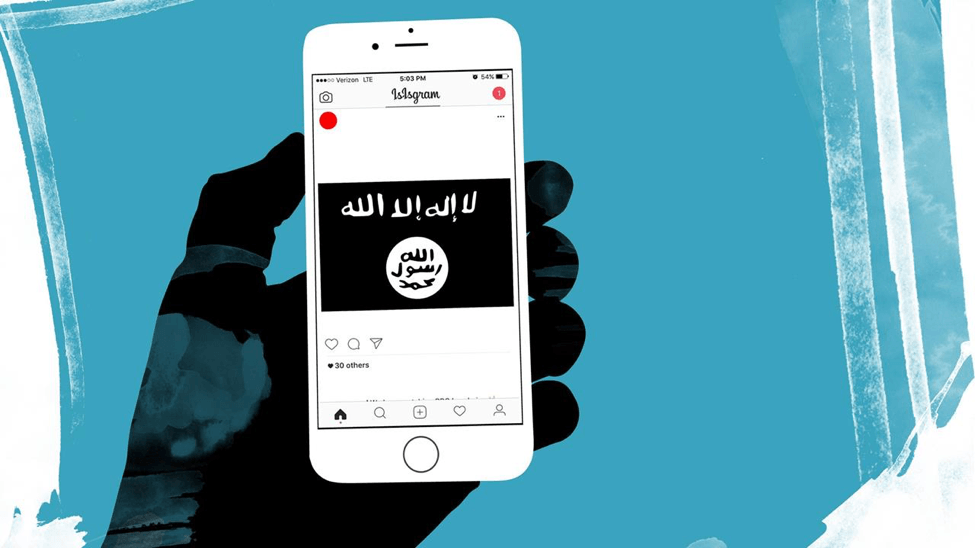

Though the international coalition in the war against ISIS has experienced more gains than losses over the past few years, by no means is the enemy defeated. However, ISIS remains a fragment of what it once was and its goals appear even more unattainable. ISIS will never fully disappear. Its ideology is just as dangerous as its fighters, and while fighters can be physically defeated, an ideology cannot. This is especially true in the era of the internet, where an entity does not need to control a territory and its people to espouse ideas and maintain a following. While ISIS, as a physical organization, may become greatly diminished to the point it seems non-extinct, radical extremist ideology will prevail.

Background

ISIS formed out of Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI), a splinter group of Al-Qaeda central that emerged after the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 and aimed to entice a sectarian war and establish a caliphate [1]. In 2006, AQI was rebranded as the Islamic State in Iraq (ISI). They held a large swath of territory in Western Iraq, but in 2008, U.S. troops and Sunni tribesman significantly degraded the group [2]. As the Syrian Civil War ramped up in 2011, ISI used this state of turmoil in which the government was distracted by rebel groups, to try and govern land, led by their Caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi [3]. After U.S. combat forces withdrew, a vacuum was created that allowed the Islamic State to exploit the “weakness of the central state” and the “country’s sectarian strife” [4]. After growth in Syria, in 2013 the group began seizing land in Iraq leading to the adoption of the name Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) [5].

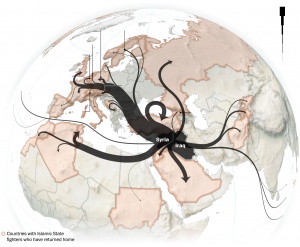

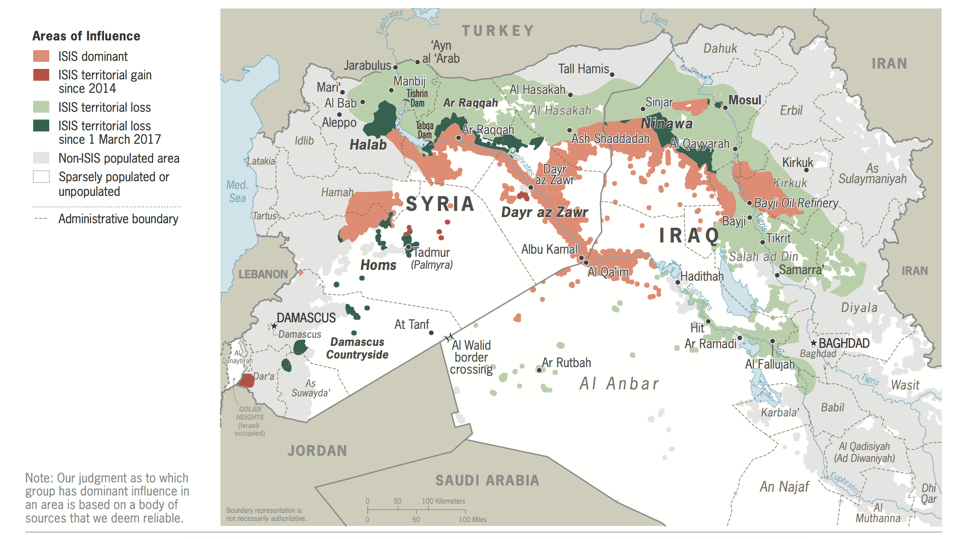

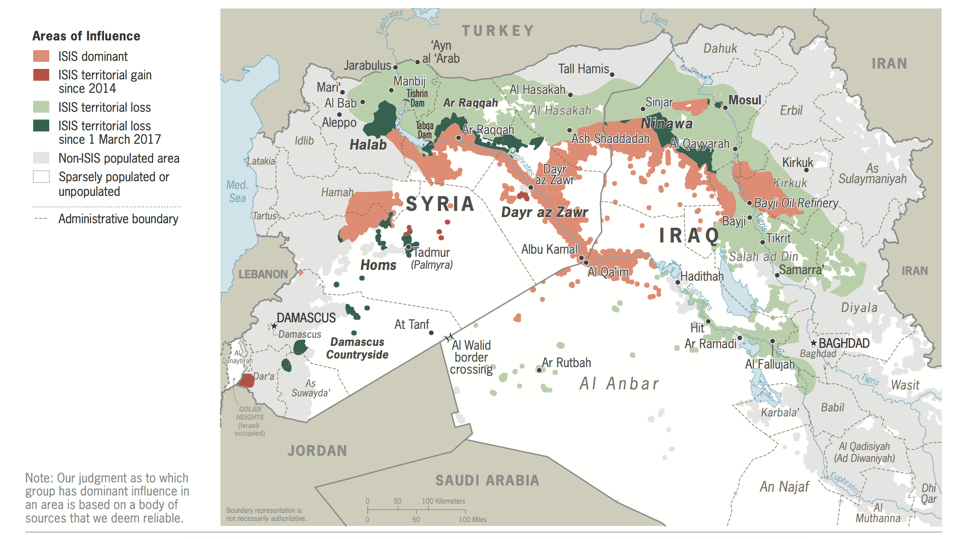

In June 2014, ISIS seized Mosul and announced the creation of a caliphate. This move prompted military action from the U.S. in the form of Operation Inherent Resolve. According to the Department of Defense, as of August 2017, the Coalition had conducted 13,331 airstrikes in Iraq and 11,235 airstrikes in Syria. As of May 2017, ISIS has lost 70% of the territory it controlled in Iraq in 2013 and 51% in Syria [6]. ISIS is rapidly losing its seized territory, and with it goes its dreams of a global caliphate.

Iraq and Syria: May 2017 (Source: theglobalcoalition.org)

Why Won’t Traditional Counterterrorism Work Against ISIS?

ISIS’s goal is to establish a caliphate and enact Sharia law. The counterterrorism tactics used against ISIS did little to degrade them initially. According to David Kilcullen of the book Out of the Mountains: The Coming Age of the Urban Guerilla, ISIS does not hide out in rural deserts like past terrorist groups; they live in urban areas amongst civilian populations. This means drone strikes are difficult because of the almost guaranteed collateral damage. Furthermore, killing leadership will not harm the group because of its cell-like structures. Attempts to cut off funding did very little to degrade the group because the land they held sustained them with oil fields, banks, and antiquities. Countering their propaganda remains difficult because young, susceptible men find the ideology incredibly inviting. Pure military strength has taken most of the physical caliphate away from ISIS, but their ideology remains and their ability to inspire attacks is an enduring threat. Thus, the answer to the question is such – traditional counterterrorism did not work against ISIS because ISIS is an insurgency, not just a terrorist group.

Will ISIS be Defeated?

According to Audrey Cronin, Professor of International Relations at American University, ISIS is not a terrorist organization; it is an insurgent group that uses terrorist tactics [7]. This is important to keep in mind when attempting to discover what the future may hold for ISIS, as well as figuring out what are the best ways to respond to the continued threat. It is still absolutely vital to respond to the terroristic aspects of the organization, but it is important to keep in mind that the end of terrorism does not mean the end of its other elements.

Cronin has explained six ways in which terrorism ends – success, failure, negotiation, repression, decapitation, and reorientation [8]. ISIS will not succeed in establishing a global caliphate; it has lost too much territory and it was never a truly achievable goal. It will not fail or self-destruct because it functions in a cell-like structure, so while one cell may struggle, another cell can still operate unaffected. Negotiation is not feasible as the group’s demands are simply too ludicrous. Decapitation, in which a leader is killed or arrested, will do nothing to degrade ISIS because, while Baghdadi is a powerful symbol and well versed in Quranic studies, he is just that; a symbol of the movement, but not a real leader [9].

SEAN CULLIGAN/OZY

Reorientation is how ISIS will end; they will transform into a different type of group. It is important to note that the end of terrorism does not mean the beginning of peace [10]. ISIS will no longer remain an insurgent group that uses terrorism as a tactic, but they will continue to pose a threat in terms of sporadic attacks via its cells. Daniel Shapiro, professor of International Affairs at Princeton, does not think ISIS “has significant prospects for renewed growth anywhere” but does agree that the threat of attacks do remain [11].

What Will Work Against Radical Ideology?

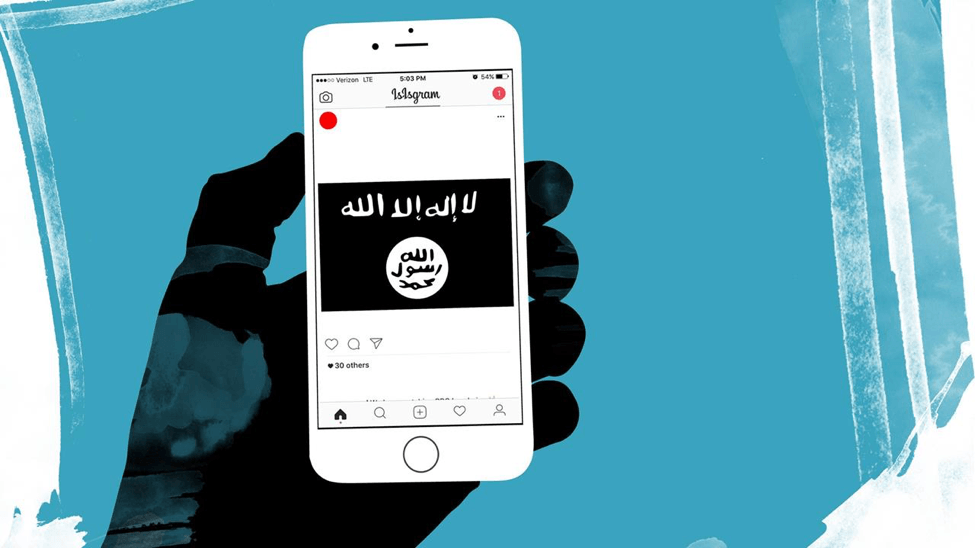

The threat of terrorism will never fully go away. Diminishing ISIS’s territory has hindered their ability to finance themselves, coordinate, and plan large-scale attacks. However, taking away their physical caliphate does not mean ISIS cannot continue to propagate on the internet in the form of a virtual caliphate. We cannot win a war on ideology with weapons. The threat of a global caliphate is no longer existent, but the dangerous ISIS-inspired mindset will remain. As Scott Atran argues in his book Talking to the Enemy: Religion, Brotherhood, and the (un)Making of Terrorists, de-radicalization, just like radicalization, works from the bottom up, not the top down [12]. This begs for continued advancement of community programs, including those that stress education and reinterpreting theology, to ensure susceptible young men and women do not radicalize via the internet, as well as collective vigilance to stop homegrown attacks.

Sources:

[1] http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/11/19/AR2007111900721.html

[2] http://www.cnn.com/2016/08/12/middleeast/here-is-how-isis-began/index.html

[3] The ISIS Apocalypse. William McCants 2016.

[4] https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/isis-not-terrorist-group

[5] http://www.cnn.com/2016/08/12/middleeast/here-is-how-isis-began/index.html

[6] http://theglobalcoalition.org/en/maps_and_stats/daesh-areas-of-influence-may-2017-update/

[7] https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/isis-not-terrorist-group

[8] How Terrorism Ends. Audrey Cronin. 2009.

[9] http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/06/30/can-the-islamic-state-survive-if-baghdadi-is-dead/

[10] How Terrorism Ends. Audrey Cronin. 2009.

[11] https://www.princeton.edu/news/2017/10/20/shapiro-what-fall-raqqa-means-future-isis

[12] Talking to the Enemy: Religion, Brotherhood, and the (un)Making of Terrorists. Scott Atran. 2010.