As ISIS concedes its last remnants of territory, governments around the world must confront the return of foreign fighters from Iraq and Syria. These fighters present many issues as they now have combat experience, support networks, and knowledge that can be used to create devastation. To explore the threat that returning fighters pose to nations around the globe, this article will first discuss the fighters’ backgrounds, explaining why some countries will have a higher influx of fighters than others. Next, it will discuss what expertise these fighters bring. Finally, it will discuss the global implications of the fighters’ return.

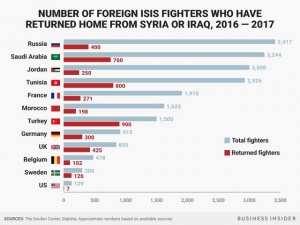

Image source: The Soufan Center/Statista/Mike Nudelman/Business Insider

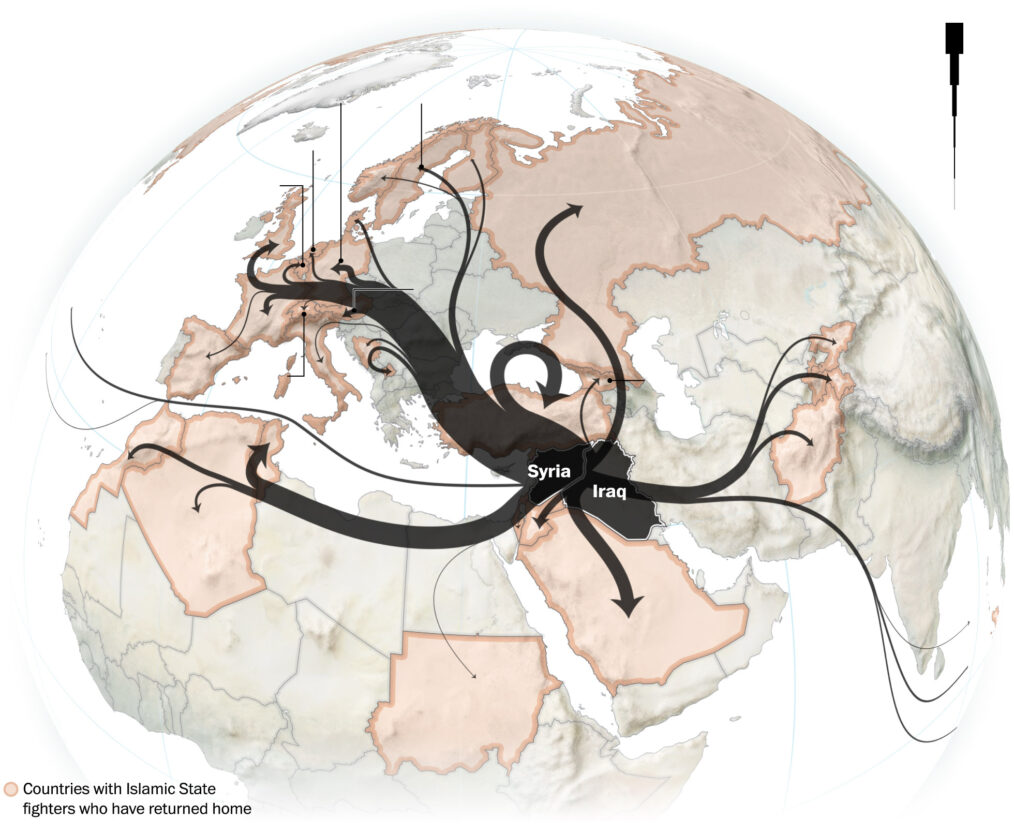

Many people around the world believe that the makeup of the Islamic State is predominantly males of Middle-Eastern nationality. This is not an unreasonable assumption, given that the primary theatre of group operations is in Syria and Iraq. However, its’ members nationalities are diverse. Since the group’s inception in 2013, ISIS has attracted those from every corner of the globe, from the United States to Russia. According to a study by the Soufan Center and the Global Strategy Network, thousands of fighters have already returned to Europe and other countries in the Middle East from the conflict in Syria and Iraq. Of the estimated number of foreign fighters that have joined ISIS, around 30 percent have returned to their home countries (EPRS, 2018). Collectively, over 1,000 trained ISIS fighters have returned to the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Belgium (Meko, 2018). 900 have returned to their native countries of Turkey, 400 to Russia, and 760 to Saudi Arabia (Meko, 2018). However, these numbers only include fighters that have been confirmed to have arrived- so the actual number of returned fighters is likely much higher.

Foreign women and children are also playing a noticeably larger role. According to a report from the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation at King’s College, approximately 41,490 foreign citizens became affiliated with ISIS from April of 2013 to June of 2018. Of this number, 13% were women, while 12% were minors. Women and minors accounted for approximately 23% of all British ISIS affiliates (Khomami, 2018). Like the men returning from conflict, each of these women and children may pose a major threat as well.

Fighters who have experience engaging in terrorist activities and operations in Syria, Iraq, and other countries in the Middle Eastern theater pose a serious threat for a number of reasons. First, through training and experience, they have mastered the use of weapons such as improvised explosive devices (IEDs), guns, vehicles, etc. They have learned an array of methods to inflict the maximum number of casualties possible. Second, these fighters will likely try to pass on their knowledge to others interested in committing acts of terrorism. Many areas throughout Europe have already become hotbeds of radicalization; for example, the Brussels suburb of Molenbeek has produced many Islamic extremists linked to terrorist incidents around the world, such as the 2015 Paris attacks. As hundreds (or possibly thousands) of foreign fighters return to Europe, they may target and train other radicalized individuals in places such as Molenbeek. There are many implications for European governments, who must take heed, prepare to apprehend these fighters, and prevent the spread of radicalization and training to at-risk populations.

Ultimately, the fall of ISIS in Syria will create an outpouring of foreign fighters. A proactive approach to apprehending these individuals is one of the best methods to prevent fighters from passing on their knowledge to others. Given the proximity of many countries in Europe to one another, it is easy for extremists to create international networks to facilitate attacks. By apprehending foreign fighters immediately upon their return, authorities can prevent them from galvanizing already-established networks in Europe- decreasing the likelihood of an effective, coordinated attack, and potentially saving hundreds or thousands of lives.