Since the refugee crisis’ start in 2015 Europe has been under considerable strain. Tension and anger commingle as Europeans grapple before the world with their humanitarian duty and concern over their increased risk at the hands of Islamic terrorism. There were only two reported terrorist attacks linked to Islamic extremism in 2014. That number has multiplied many times since the refugee crisis’ start. There were 17 attacks in 2015, 13 in 2016, and 33 in 2017.

The EU’s Approach to Migration

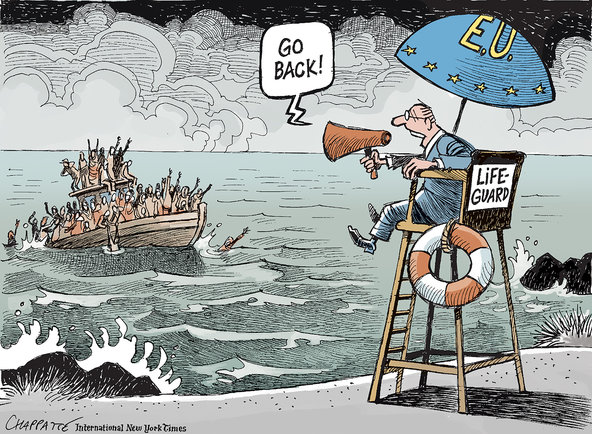

The European Union’s grand migration strategy states that, “…rising to the migration and refugee challenge — and doing so in full respect of human rights and international law — is a vital interest at the core of the EU’s values.” But the statement has been challenged within the EU itself.

The grand strategy attempts to address concerns about terror’s growing threat in Europe, but it does imply that it is the EU’s duty to welcome those in need. Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland, however, have actively resisted accepting large numbers of refugees. The Czech Republic and Poland may soften their stance. But Hungary continues to resist EU migrant norms. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has been accused — in a conspicuous breach of EU core values — of anti-immigration policies, attacking the rule of law, and minorities in the media. While unlikely to lead to real punitive action, the accusations lead to Hungary’s losing its vote.

The EU is known for implementing the Schengen Agreement among 26 countries to abolish borders within the Union. The agreement is a cornerstone of European unity. But six EU countries including France, Austria, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, and Norway have agreed, in light of increased terrorism, to temporarily reinstating internal border controls.

The agreement is surprising and the rationale, startling. “Persistent terrorist threats,” “security situations,” ”threats resulting from continuous significant secondary movements,” and, “continuous serious threats to public policy and internal security,” represent some of the verbiage being bandied about. The most significant citation, “…significant secondary movement” relates to the Schengen Agreement’s position regarding free movement between states.

Populism in Europe and the Anti-Immigration Argument

Italy, Sweden, and Germany are now pushing back against EU immigration policies. The four nations have seen their politics become more nationalistic and anti-immigration. While not every country is experiencing a populist turn like Italy, right-wing populist groups are ascendant elsewhere. One of Europe’s most notable changes in the past decade is the disintegration of support for established, left-wing parties. There has been a commensurate increase in right-wing, populist affiliation. And such groups traditionally hold anti-immigration stances. In 2018, Pew research found that social democratic parties are hitting all-time lows over most of Europe.

Circumstances have put Italy’s no-boat policy to the test repeatedly

Italy’s new populist government took power over the summer and has made moves to boldly enforce anti-migration policies. Interior Minister Matteo Salvini said on record, “Not one more person arrives in Italy by boat.” In a more nuanced pronouncement later Salvini said he doesn’t oppose helping refugees, and he has pledged to allow refugees, especially pregnant women, and children stay in Italy. But he added that he continues to see migrants traveling by boat as a serious threat to Europe.

Circumstances have put Italy’s no-boat policy to the test repeatedly. In June, before Salvini’s statement, the Italian government refused disembarkment to a ship carrying 600 migrants. This led to a standoff between Rome and the EU. The tension abated when Spain volunteered to receive the ship. While that represented a win for Salvini, two months later, in August, Rome caved to EU pressure and allowed a ship with 150 migrants to dock.

Germany and Sweden too have seen increases in populism and anti-immigration rhetoric. The Sweden Democrats, an anti-immigrant, pro-welfare-state party, won 18% of the vote. Comparatively, political powerhouse, the Social Democrats suffered 11% losses in union support. This saw them drop to the third most popular party in Sweden. It is noteworthy that the Social Democrats received few youth votes. These developments suggest a long-term political shift in Sweden.

Germany experienced similar political seismic shifts in 2017. The success of the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) makes it the first far-right group to hold seats in the Bundestag in 50 years. AfD mirrors other right-wing groups throughout Europe: each embraces a platform of anti-immigration and emphatic German nationalism. A striking aspect of AfD’s success is that since 2013, the party gained 7.9% growth in support. It draws from all German regions, while the country’s traditional parties such as Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (Christian Democratic Union of Germany, CDU) and the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (Social Democratic Party of Germany, SPD), suffered substantial losses all over the country.

EU policy should protect European citizens without turning its back on a humanitarian crisis.

Looking Forward

In light of immigration trends, increasing terror attack rates, and populist waves plaguing Europe, the EU must unify behind the values, and goals its member states share. It must continue counteracting growing populism movements. And it must reassess how it can address the refugee crisis. Recently, President Jean-Claude announced that the EU would deploy 10,000 armed border police — with the freedom to use force — on the EU’s external borders to tackle unlawful immigration. While this is a step in the right direction for European security, it is imperative that the EU listens to all member states. It must not deny the real dangers caused by unchecked immigration. But fear should never outweigh the moral responsibility to help fellow humans in need. EU policy should protect European citizens without turning its back on a humanitarian crisis.

This cartoon by Patrick Chappatte appeared in the April 25, 2015 International New York Times. He titled the cartoon “Migrants and the European Union,” and added the caption, “Europe looks for an answer to the migrants reaching for its shores.”Credit Patrick Chappatte