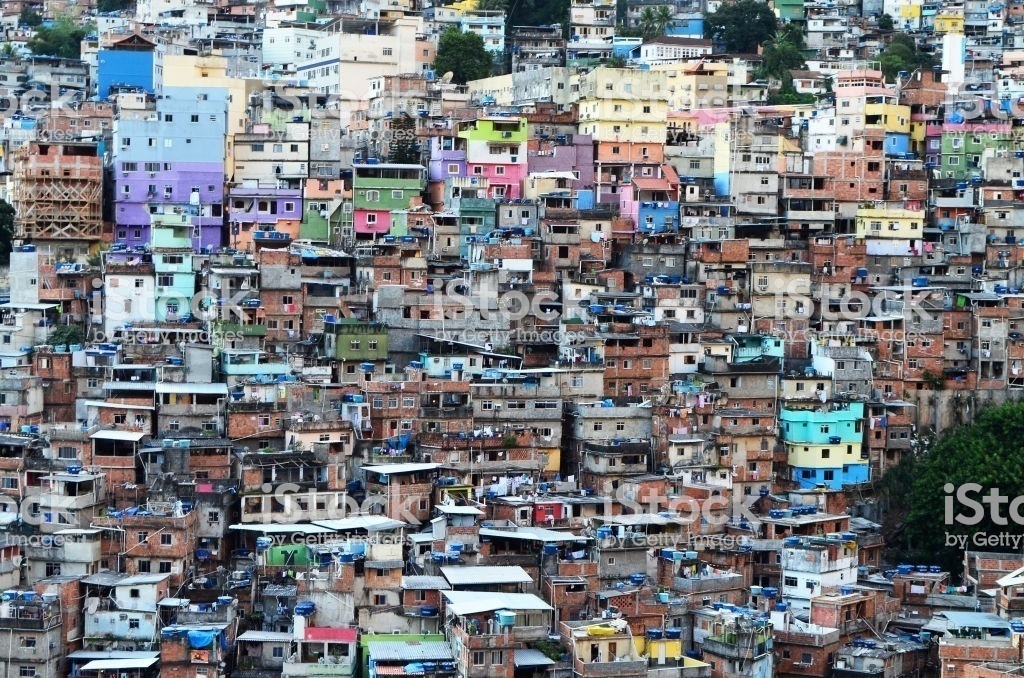

Source: The Washington Post/Alex Gomes/AP

Author: Cameron Cassar

The newly elected right wing president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, had just been newly inaugurated when he had to deal with his first security crisis; terrorism attacks led by prison gangs in the Brazilian state of Ceara. The attacks have been centered on the capital of Ceara, Fortaleza, which is a metropolitan home to about 4 million Brazilians. These attacks have destroyed homes, businesses, modes of transportation, and has left many residents stuck in their homes due to threats of violence.

All of these attacks have been motivated by a desire to get the Brazilian government to end the practice of segregating gang factions in the Brazilian prison system. This goes completely against Bolsonaro and his ideologies. In fact, a major point of his political platform was that he vowed to enact strong policies to combat crime in Brazil. These policies include military takeovers in crime ridden Brazilian cities and shoot to kill policies for violent criminals.

This current wave of violence in Brazil shares many similarities to the wave of violence led by Pablo Escobar and the Medellin Cartel during their reign of narcoterrorism in Colombia. However, while the Brazilian prison gangs have opted to mainly use violence, the Medellin Cartel not only committed violence to instill fear in lawmakers in Colombia, but they also bribed police officers to turn a blind eye towards their criminal activities. Importantly, both of these organizations have used “violent lobbying” tactics to scare lawmakers into implementing policies that benefit them. Pablo Escobar wanted to get rid of extradition while the Brazilian gangs want to eliminate desegregation in prisons. The gang leaders want to end the prison reform which includes ending the separation of rival gang members and the blocking of cell phone service in the prisons.

These reforms would hinder the effect of the gang leaders who are locked up inside of the prison by disconnecting them from the outside world, which gives them the chance to coordinate their attacks. However, many gang leaders do not want desegregation in the prisons because they fear for their safety amongst the other prisoners who are often times rival gang members with a personal vendetta against one another. Incidentally, the violent lobbying of the gangs has united them in an unusual alliance due to the “common enemy”. The First Capital Command and the Red Command, two of the biggest gangs in the area have already formed a pact and there are plenty more that will be formed as the conflict ensues.

Brazil has the third highest prison population behind China and the US (of course). The problem is that President Bolsonaro wants to be even tougher on crime, which will result in even more Brazilians being sent to prison. Some of the policies he wants to implement include lowering the age of criminal responsibility from age 18 to age 16, which will only increase the number of Brazilians in the prison system. More Brazilians in the Brazilian prison system will not help reform the broken prison system. If anything, the country needs less prisoners so they can focus on improving the conditions in the prisons due to the overcrowding. The point of prison is to rehabilitate the prisoners so they can be reintegrated into society when they are released, but a prison in bad condition and ran by the prisoners instead of the guards is not suitable for rehabilitation.

President Bolsonaro must now deal with the crisis that has begun to unfold in his country. However, many members of the left saw this wave of terror coming. As Renato Roseno of the Socialism and Liberty Party stated, “This crisis was entirely predictable, we were sitting on a barrel of gunpowder and it just needed someone to light the fuse”. It is now up to him to decide if he will counter these actions, if he will send in foreign help, will peacekeeping troops be deployed, and will he still be able to stick to his tough on crime policy? It will be interesting to see how Bolsonaro deals with his first major crisis as a president. Will he be able to stick to his hard right policies or will he be pressured to renege on the promises that got him elected as president in the first place?