After weeks of increased violence, uncertainty, and a stalemate between the negotiating parties, talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban resumed earlier this week in Doha, amid a looming deadline for US troops to fully withdraw from the country by May of this year. Despite the flurry of historic developments that have taken place in Afghanistan over the past year, the next couple of months will be a critical test for both the momentum of the peace process and the patience of the major players involved.

For the Biden Administration, the outcome of the dialogue in Doha will be the first major foreign policy challenge, one that will either culminate in a historic agreement or continued entrenchment for what has already been America’s longest war. Public opinion polls conducted amongst a diverse group of American voters suggest that while most have experienced fatigue with the conflict, very few support a complete withdrawal of US troops, even when accounting for partisan differences.

Nevertheless, a full drawdown would likely strengthen the Taliban’s position, and encourage a repeat of the chaos that ensued in the aftermath of the withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1989, and the cessation of Soviet foreign aid in 1991, which quickly brought down the government of Mohammad Najibullah a year later.

The Taliban’s current fighting force (estimated between 40,000-60,000 fighters) would take complete control of Afghan territory, highly unlikely. However, a potential breakdown of the current unity government, buttressed by the Taliban’s enduring connection to both Al-Qaeda, and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant-Khorasan Province (ISIL-Khorasan), would whet the Taliban’s risk appetite for sustained engagement with the Afghan armed forces as seen in the past months.

Given the fragility of the Ghani government, and waning enthusiasm from the American side, the Biden Administration’s best option is to pursue a compromise that would postpone their scheduled withdrawal in May and buy more time for the negotiators. Dr. Amin Ahmadi, who is a member of the Afghan government’s negotiating team, notes the importance of a clear American policy. “I think they can pursue a multi-pressure strategy. First, the US exit from Afghanistan should be condition-based on peace in Afghanistan. The Americans should make it clear to the Taliban that if they don’t want peace, they will stay in Afghanistan.”

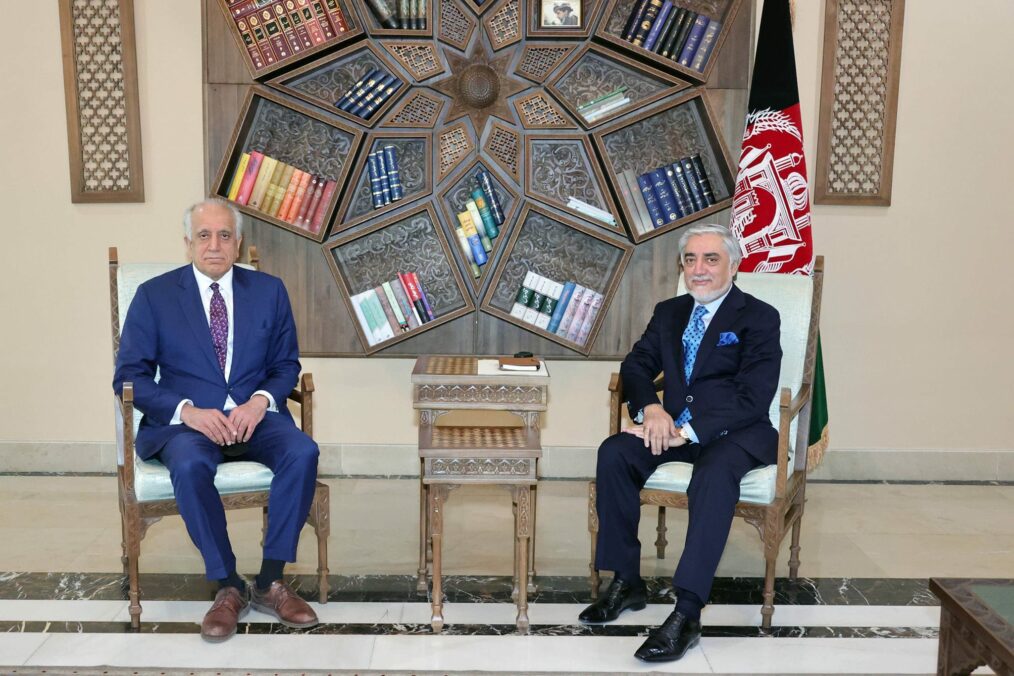

At present, US policy toward Afghanistan remains vague, and although President Biden’s approach is expected to be a marked departure from that of his predecessor, it appears unlikely that he will undo either of two signature moves made by the Trump Administration, including the existing withdrawal agreement, and the recent drawdown of American troop levels to their present level of 2,500. Key personnel tied to the current deliberations, most notably US Special Envoy Zalmay Khalilzad, are also expected to be retained in the Biden Administration’s foreign policy team.

Ahmadi adds that the “Taliban have the upper hand at negotiations, not because of the US-Taliban deal, but because they can simply walk away from the talks and go back fighting. The Doha agreement has defined the US troops withdrawal condition-based so there is no pressure on Taliban at the moment.” The Taliban has also benefited from the successful release of imprisoned fighters, and the international legitimacy that the US peace deal conferred to its organization and its external relations with foreign powers.

The recent recess in peace talks saw the Taliban appeal to Iran, Russia, and Turkey in a bid to cultivate support and obstruct US efforts to put pressure on regional actors. In the event that calls for an interim government (one that would presumably replace Ghani) go unheeded, the opportunity would be ripe for the Taliban to exploit factionalism between Ghani’s supporters and political rivals.

Khalid Noor, the youngest member of the Afghan government’s negotiating team, notes that the “interim government is preferred by a majority of the political community, however, there should be some sort of guarantee by the Taliban, along with the support of regional actors before such a thing could happen.” Yet, Ghani and his supporters have been steadfast in their opposition to such a plan, suggesting that a premature conclusion of his term would be a rebuke of Afghanistan’s republic system. Nevertheless, even if Ghani agrees to a transfer of power, Dr. Ahmadi suggests that “the question of an interim government should be part of the solution, not the solution.”

In order to reach the ideal scenario of a postponed withdrawal, the United States will likely have to lean on its existing relationship with state actors in lieu of a direct appeal to the Taliban. While generating strong buy-in from the likes of Russia, Iran, and Turkey is unlikely in the next 2 months, the Biden Administration does possess leverage over the Taliban’s main source of financial support (member-states of the Gulf Cooperation Council) and political support (Pakistan).

Ahmadi agrees, noting that “the most important country for the Taliban in Pakistan, and when Pakistan is under American pressure, it will help the peace process.” By wielding the threat of sanctions, the United States could fulfill Pakistan’s long-standing demand to be removed from the Financial Action Task Force (FATF)’s “grey list”, which would provide relief for Pakistan’s access to global capital markets and encourage foreign direct investment.

The economic argument for peace in Afghanistan has only grown stronger given the presence of lucrative natural resources, particularly mineral wealth, and the favorable location that could help the country generate transit fees from energy projects and improved infrastructure to facilitate trade between East and West Asia.

Dr. Adib Farhadi, an Assistant Professor of Peace & Conflict at the University of South Florida, believes the economic case could be compelling to win support from regional players like Russia, China, Pakistan, and Iran. “You counter violent extremism by winning hearts and minds, which includes giving Afghans jobs. Afghanistan is a rich country, but the economics only works if everyone is included.” The recent commodity boom bodes well for the resources found in Afghanistan, with technology-critical elements like Lithium and Rare Earth Elements in a large abundance.

With little more than 60 days remaining before US troops are scheduled to withdraw, the next set of developments will be a harbinger for the trajectory of the peace process. Sustaining the momentum of the milestones achieved in the past year will require difficult political compromises from a long list of state and non-state actors.