As Afghanistan descends into conflict amid the US withdrawal, President Biden and senior military leaders have pledged to maintain “over-the-horizon” capabilities. This is to prevent the fall of Kabul and terrorist organizations from using Afghanistan as a safe haven. The Afghan air force is in an increasingly precarious position to support ground forces. This is because the contract personnel responsible for maintaining its aircraft left with US forces.

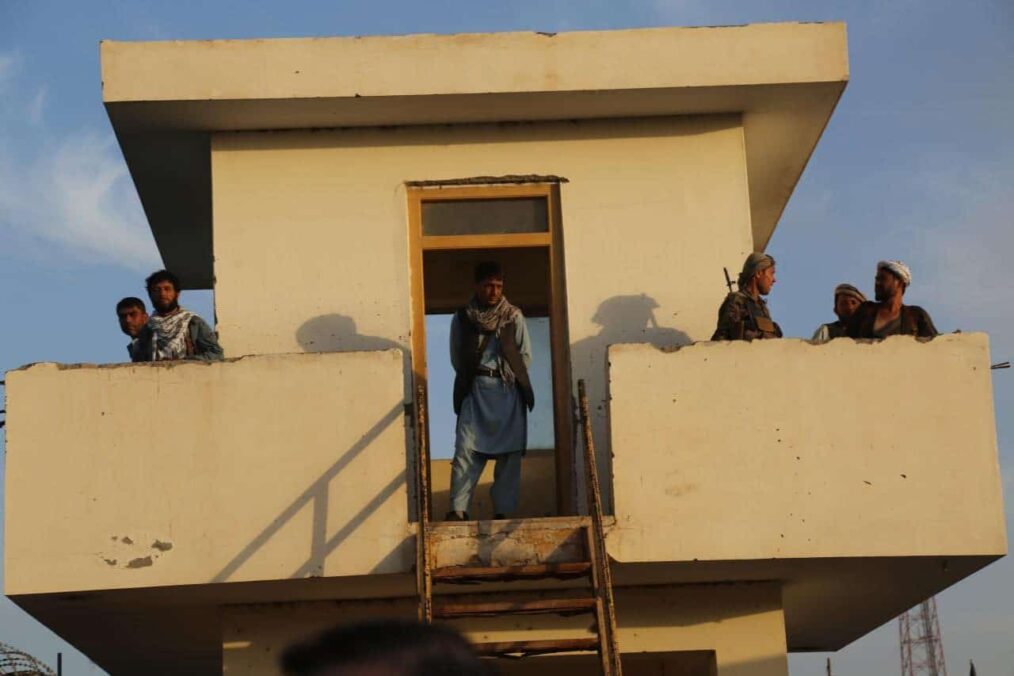

As seen by recent Taliban victories, without the threat of air support from the last 20 years, the future of Afghan forces to defend against Taliban offensives is grim. Therefore, it is crucial to understand OTH strategies to effectively assess its potential as an alternative to on-the-ground forces.

Over-the-horizon refers to the capacity to detect, neutralize, and monitor threats from very long ranges using manned or unmanned aircraft. This often comes from hundreds or thousands of miles. The collapse of ANA ranks amid Taliban pressure makes this strategy one of the only ways to slow the Taliban’s advances and counter-terrorists threats.

OTH offers several advantages; it can bypass Afghanistan’s rugged terrain which hindered ground troops and facilitated easy movement for militants. Furthermore, it is not constrained by frontlines. Subsequently, it can now deal debilitating blows to enemy positions, supplies, and infrastructure anywhere in the country. It was arguably the main reason why the Northern Alliance broke the months-long stalemate with the Taliban after 9/11. Similar campaigns in Iraq, Syria, Serbia, and Pakistan provide interesting case studies to evaluate the future viability of OTH targeting in Afghanistan.

The use of air assets in Kosovo, Serbia was one of the first extensive uses of OTH strategy. Because drone technology was in its infancy, techniques to attach munitions to UAVs were not utilized. These made them strictly surveillance platforms. To neutralize targets, they laser-designated the enemy personnel or equipment which would be transmitted to manned aircraft to conduct the strike. Although drones can carrying considerably more weaponry now, this two-aircraft approach may allow for great capacity to target Taliban positions.

Manned aircraft can carry more ordinance and may assure military leaders with two confirmations (human and video) of targets. Serbian soldiers quickly adapted to UAV strikes by placing anti-aircraft gun in most likely flight paths, concealing tanks and artillery under foliage or infrastructure. Like all enemies, the Taliban and Al-Qaeda will have adapted to 20 years of drone attacks. Likewise, OTH must similarly adapt to counter their tactics.

Across the border in Pakistan, OTH was used extensively to eliminate militants. These were mostly used against those who exploited the Afghan-Pakistan border to avoid death, much to the anger of Pakistani officials. UAVs mitigated physical risk to pilots who could be shot down. Similarly, political risk was mitigated to the President, who would receive backlash for violating a country’s sovereignty. UAVs still crossed into Pakistan but at much lower risk. Subsequently, they presented more favorable optics than a human pilot entering Pakistani airspace.

Despite media reports of drones indiscriminately killing civilians, they were privately supported by Pakistani military leaders and by some civilians. Those of who had grown tired with Taliban atrocities.

According to senior government officials, UAV civilian deaths were routinely reported incorrectly. Consequently, they proved extremely precise in eliminating only Taliban and Al-Qaeda-linked militants. Unfortunately, the death of civilians likely created anti-American sentiment and makes it difficult to evaluate the campaign’s overall effectiveness. Much like the increased safety and precision by drones in Pakistan, an OTH strategy using manned and unmanned aircraft will only increase target precision when used in Afghanistan.

OTH campaigns in Syria and Iraq by Russian and US air assets in their respective conflicts differ from those in Pakistan. This is because they actively support a ground offensive, which is the more traditional way of using airpower. The intervention of each country’s air force decisively changed the course of the conflict. This included saving Bashar Al-Assad from near collapse and giving Iraqi forces a much-needed boost to drive ISIS from its positions in Mosul. The presence of ground troops who were aware of how to communicate with air assets, however, distinguishes this campaign from Afghanistan.

The presence of airbases in-country also contributed to the ability to launch quick, reactive strikes. This is something that is now lost. Tens of thousands of airstrikes later and likely more to come, the OTH strategy gave the Iraqi and Syrian governments time to reorganize their forces and stop their oppositions’ momentum. The objective is similar in Afghanistan. However, policymakers must understand the general limitations of OTH and how Afghanistan’s unique tactical environment could limit its effectiveness.

Afghanistan presents unique challenges to implementing superior air power against the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. The obvious difference is that without airbases, pilots and UAV will have to fly six to eight hours to get to Afghanistan. This is due to the closest airbases being located in the United Arab Emirates or Kuwait.

The inability to secure basing in Central Asia and Pakistan may severely limit quick strikes. Furthermore, this may provide time for the enemy to move away from the target area. The lack of US presence on the ground will also complicate air-to-ground coordination for strikes. Afghan forces have yet to prove their abilities to remain cohesive under pressure and communicate well with pilots.

In asymmetric warfare where the Taliban blend into the local populace and lack traditional infrastructure attack, OTH is limited. This is without extremely precise discrimination between civilians and combatants. Thus, military leaders must constantly push innovation to increase strike precision. They should also consider how covert, lethal aid by Russia or Iran will pose risks to airframes. This is especially important, with anti-aircraft missiles.

A robust OTH strategy is the only way to delay the Taliban’s quick gains and ensure peace can be implemented in Afghanistan. The ability for Afghan troops to coordinate these strikes with US aircraft will determine the strategies overall success. Over-the-Horizon targeting has the potential to deal devastating blows to the Taliban’s momentum and maintain the remaining stability in Afghanistan. However, US leaders must understand its limitations and constantly push the military to innovate lighter, stronger, and more precise air capabilities.