Introduction

With the sheer saturation of terrorist attacks occurring each week, US news outlets are forced to make decisions regarding what gets published. Characteristics of terrorist attacks such as casualty toll, perpetrator, or weapon type often determine newsworthiness and thus which attacks get covered. While past research has focused on coverage of domestic terrorist attacks within the United States, this paper examines determinants of US major media coverage of terrorist attacks across the globe. Using data collected over the past year, we examine the distribution of characteristics of large-scale terrorist attacks that did and did not garner coverage by major US news outlets.

Background

Media coverage of terrorism strongly influences how the news-consuming public interprets both terrorist attacks and the political and cultural impact that terrorist attacks have on society. Coverage of terrorist events occurring in the United States between October 2001 and January 2010 reveals a media paradigm “in which fear of international terrorism is dominant, particularly as Muslims/Arabs/Islam working together in organized terrorist cells against a ‘Christian America,’ while domestic terrorism is cast as a minor threat that occurs in isolated incidents by troubled individuals” (Powell 2011) [1]. Güven (2018) writes that the media has a powerful ability to shape dialogue surrounding terrorism [2]. This dominant paradigm causes individual terrorists to be linked by government and media to overarching ideologies, which results in “intensified anti-terrorism legislation, snares of rumors, and disinformation in the name of public debate.” Since media coverage of terrorism shapes public sentiment and government policy, understanding the driving factors behind this coverage is vital to the study of the political, cultural, and economic realities of terrorism.

Prior research has demonstrated that a number of attack characteristics influence media coverage of terrorism. Chermak and Gruenewald (2006) examine terrorist incidents occurring in the United States pre-9/11 and find that a number of characteristics including region, seriousness, target type, and tactics influence New York Times coverage [3]. Attacks taking place in the northeast are covered more often than those taking place in other regions of the country, and attacks causing at least one death are almost fully covered while those without death tolls are covered around half the time. They also find attacks on civilian or airline targets result in more coverage than attacks on government or NGO targets. The same holds for attacks using firearms and hijackings which are covered significantly more often than other types of attacks. Kearns et al. (2017) find that post-9/11, Muslim perpetrators, the arrest of the perpetrator, law enforcement or government targets, and casualty rates all increase media coverage of terror attacks [4]. Media coverage decreases when the perpetrators are unknown or attacks target out-groups such as Muslims or other minorities. However, saturation of coverage also increases the threshold of an attack’s newsworthiness necessary for it to garner attention. Well before 9/11, Weiman and Brosius (1991) note that as terror coverage becomes more frequent and thus normalized, the number of victims for an attack to be covered increases as well [5]. As terrorist attacks become routine, that which was once newsworthy to many media outlets, is no longer worth mentioning.

Media coverage of terrorism resonates beyond the viewers it intends to attract with far-reaching implications. Because terrorist attacks are frequently motivated by the desire to bring attention to the perpetrators’ cause, increased media coverage of terrorist attacks often causes more attacks. This effect holds across multiple forms of media. Jetter (2017a) finds that one article on a terrorist attack results in approximately 1.4 future attacks in the same country over the next week, resulting on average in three additional casualties [6]. Jetter (2017b) also finds that one minute of Al-Qaeda coverage on a major news network results in one attack in the next week, resulting in 4.9 additional casualties on average [7]. However, Asal and Hoffman (2016) find a dampening effect of media coverage on cross-border terror. They find that “the more attention a country gets from international media sources, the less likely terrorist organizations operating within that state are to launch attacks outside their national borders,” and that terrorists active in states that receive little media coverage launch international and cross-border attacks requisite to promulgate their beliefs. Therefore, media coverage of terrorism can impact the frequency, location, and perpetrators of terrorist attacks, with a corresponding impact on lives.

While prior research has focused largely on domestic attacks in the United States, this work is oriented towards global attacks significant in their casualty tolls. Characteristics that impact media coverage of terrorist attacks are analyzed to determine how major US media outlets select which attacks to cover when their viewing audience may be unfamiliar with the context, perpetrators, or country in which the attack took place. These characteristics include casualty level, target type, weapon type, country, and terrorist group. We hypothesize that attacks with characteristics more engaging to the American public are more likely to be covered by American media. Such factors include higher casualty rates, attacks in active U.S. military deployment areas, attacks by groups well-known to Americans, and attacks with more notorious groups. We test our hypothesis by comparing the distribution of attack characteristics across attacks that did and did not receive major U.S. media coverage.

Data methodology

All records were pulled from the Rise To Peace Active Intelligence Database, running from June 7, 2017, to June 7, 2018. Using all attacks would be unrealistic: news saturation of terrorist attacks means only attacks that are notable would be expected to receive news coverage. To mitigate this, we pull all attacks where total casualty count, a sum of killed and injured victims, is greater than or equal to 21. This number is chosen because it represents the 90th percentile and higher of the first 1,000 attacks entered into the Active Intelligence Database, which generates a sensible coverage expectation. Next, we search for articles from U.S. news sources representing the attention of the U.S. media to these attacks. For our purposes, we use sources from the top five most-used U.S. news sites: CNN, Fox News, New York Times, Huffington Post, USA Today. Information on attacks is sought using keyword configuration “[Source] [Month] [Day] [Year] attack.” If those searches did not yield a hit on an article referencing the attack in question, the attack was coded as ‘Undercovered’. If at least one search returned a hit on an article referencing the attack in question, the attack was coded as ‘Covered’. This yields sets of 108 ‘Covered’ attacks and 68 ‘Undercovered’ attacks. Next, we create distributions of the data-sets comparing the prevalence of characteristics within each data-set. We calculate for five characteristics: casualty level, target type, weapon type, country, and terrorist group. The results are visualized below.

Results

For the graphical analysis alone, we do not show characteristics whose representation among the 2 data-sets combined is less than 10. This is done to prevent conclusions on the basis of low data. Three of the five comparisons, therefore, suffered graphical exclusions of data: country, weapon type, and terrorist group. No data is excluded from the analyses of target type, casualty level. Results are shown below.

Target type

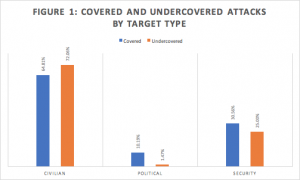

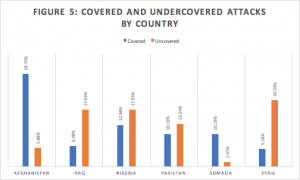

Attacks on civilian targets made up a larger portion of the undercovered attacks than the covered attacks, while security and political targets made up larger portions of the covered attacks than undercovered attacks [Figure 1].

Attacks on civilian targets comprised the largest portion of both data-sets, suggesting that civilian targets suffer from lower levels of notability due to their high frequency. This may explain the more equitable distribution of target types across covered attacks, which tend to distribute more coverage across rarer types of attacks.

Weapon type

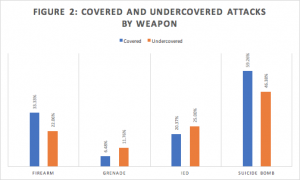

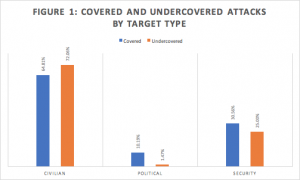

Attacks carried out using suicide bombs and firearms were greater represented in the covered attacks data-set than were attacks utilizing IEDs or grenades, which made up a larger portion of the Undercovered attacks [Figure 2].

Exclusions from the analysis of weapon type: Misc, Unknown, Mortar, Rocket

High-casualty attacks using firearms tend to be rare, large-scale assaults on targets such as security installations or entire towns, increasing newsworthiness. Suicide bomb attacks tend to inflict larger casualty rates than other explosive-based attacks such as grenades or IEDs, and their occupation of the American psyche post-9/11 is a driving force behind greater coverage. Grenade and IED attacks, while similar in execution, tend not to capture the attention of the American public in the same way as the stereotypical Muslim suicide bomber.

Terrorist group

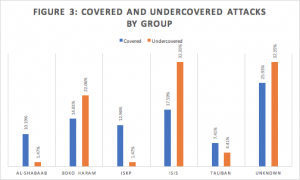

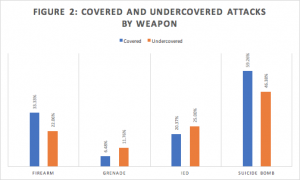

Attacks by Al-Shabaab, the Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISKP) and the Taliban made up a larger portion of covered attacks than undercovered attacks, while attacks by Boko Haram, the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and attacks by unknown actors were greater represented in undercovered attacks than covered attacks [Figure 3].

Exclusions from the analysis of terrorist group: Abu Sayyaf, AQIM, Bacham Militia, FARC, Hayat Tahrir Al Sham, [HPG,PKK], [ISIS,Jamaat ur Ahrar], Lashkar-e-Taiba, PYD, [Taliban,ISKP], TTP

The high rate of coverage of Taliban and ISKP attacks are consistent with the expectation that attacks on active U.S. military deployment areas would receive more coverage by virtue of of American attention to the area. U.S. drone strikes and special operations deployments to Somalia, as well as past U.N. commitments to the area, are similarly likely to drive attention towards Al-Shabaab’s actions in Somalia. Meanwhile, lack of U.S. engagement in Nigeria has likely reduced American attention towards Boko Haram. The finding regarding ISIS is contrary to expectations: considering high historical U.S. attention toward Iraq, as well as media sensationalization of brutal ISIS tactics and success, one would expect them to receive higher coverage levels. Finally, attacks committed by unknown actors are difficult to interpret given these attacks heavy distributions across regions.

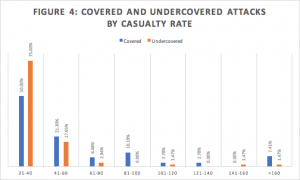

Casualty Rate

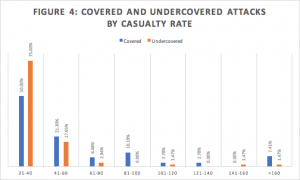

As casualty tolls increase, attacks are greater represented in covered attacks than undercovered attacks. Only attacks causing 21-40 casualties comprise a greater portion of undercovered attacks than covered attacks [Figure 4].

This result is consistent with the expectations set on coverage contingent on the notability of attacks. The redistribution of media coverage from low to high-casualty attacks demonstrates a higher premium for media coverage placed on high-casualty attacks.

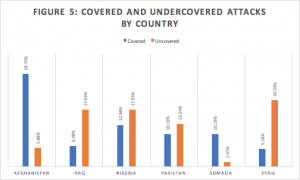

Country

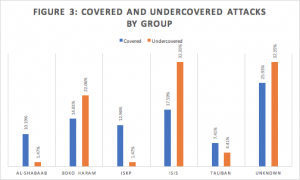

Finally, attacks in Afghanistan and Somalia make up a significantly greater portion of covered attacks than undercovered attacks, while those taking place in Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Syria are greater represented in undercovered attacks [Figure 5].

Exclusions from the analysis of country: Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Colombia, Ecuador, Egypt, England, India, Indonesia, Iran, Libya, Mali, Niger, Philippines, Spain, Thailand, Turkey, USA, Yemen

Countries with higher representation in the covered attacks data-set tend to be those with significant US military involvement and public attention in recent years. US military presence in Afghanistan and its drone and air strikes in Somalia, coupled with troop deployment drives attack coverage in those countries. Reduced military involvement in Nigeria and Pakistan means attacks in those countries garner less coverage. However, the results in Iraq and Syria run contrary to the expectation that attacks in countries with larger US involvement tend to see increased media coverage. Attacks in Iraq and Syria were significantly greater represented in the undercovered attacks dataset.

Conclusion

The results provide some support for our hypothesized proxies for notability of terrorist attacks. Attacks with higher casualty levels, suicide bombers, political or security targets, and in some areas that have active U.S. military deployment (Afghanistan and Somalia) made up higher portions of the covered attacks data than the uncovered attacks data, suggesting they receive disproportionate attention in the U.S. media. Meanwhile, attacks using commonplace tactics like grenades and IEDs, in areas without significant U.S. military presence (Nigeria and Pakistan) and attacks against civilian targets were more represented in the undercovered data.

The notable outliers are intertwined: attacks in Iraq and Syria, as well as attacks committed by ISIS, were more represented in the undercovered data than in the covered data, suggesting they received disproportionately low coverage. This contradicts our expectations for notability given that ISIS has not only launched attacks on the United States in the past, but the U.S. has active military deployments in the region. We suggest two possible explanations for this discrepancy. First, the massive volume of attacks by ISIS has introduced a saturation level to media markets dampening coverage of ISIS in favor of other groups. The pure volume of violence, even at high levels, removes the notability from the attacks and reduces coverage of the attacks. However, this explanation is likely inconsistent with the finding that attacks in Afghanistan, and even with the ISIS cell in Afghanistan, ISKP, are greater represented in the covered than the undercovered data. The U.S. also has active U.S. military deployments there, but saturation does not appear to have dampened the proportion of coverage. The second possible explanation is the distinction in the data between territorial warfare and terrorism. The Rise To Peace Active Intelligence Database distinguishes between acts of terrorism and attempts at territorial control, only including the former. However, ISIS engages in both forms of warfare, and it, therefore, may receive higher proportions of coverage for territorial warfare and therefore still receive high media attention. This apparent discrepancy, and its implications for U.S. media coverage of foreign violence in Iraq and Syria is deserving of further research.

Endnotes

[1] Powell, Kimberly A. “Framing Islam: An Analysis of US Media Coverage of Terrorism Since 9/11.” Communication Studies 62, no. 1 (2011): 90-112.

[2] Güven, Fikret. “Mass Media’s Role in Conflicts: An Analysis of the Western Media’s Portrayal of Terrorism since September 11.” International Journal of Social Science 66, Spring II (2018): 183-196.

[3] Chermak, Steven M., and Jeffrey Gruenewald. “The Media’s Coverage of Domestic Terrorism.” Justice Quarterly 23, no. 4 (2006): 428-461.

[4] Kearns, Erin, Allison Betus, and Anthony Lemieux. “Why do Some Terrorist Attacks Receive More Media Attention Than Others?.” (2018).

[5] Weimann, Gabriel, and Hans-Bernd Brosius. “The Newsworthiness of International Terrorism.” Communication Research 18, no. 3 (1991): 333-354.

[6] Jetter, Michael. “The Effect of Media Attention on Terrorism.” Journal of Public Economics 153 (2017): 32-48.

[7] Jetter, Michael. “Terrorism and the Media: The Effect of US Television Coverage on Al-Qaeda Attacks.” (2017).

[8] Asal, Victor, and Aaron M. Hoffman. “Media effects: Do Terrorist Organizations Launch Foreign Attacks in Response to Levels of Press Freedom or Press Attention?.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 33, no. 4 (2016): 381-399.

© Getty Images- Serial-bomber Mark Anthony Conditt, 23, left two dead and four injured after a series of attacks in Austin, Texas

© Getty Images- Serial-bomber Mark Anthony Conditt, 23, left two dead and four injured after a series of attacks in Austin, Texas