The effects of War:

The political, sectarian, and ideological conflicts and civil wars taking place in the Middle East since the late 1990s have had devastating effects on social, psychological, and economic frontiers. These threaten to kill the aspirations of multitudes living in and around the conflict zones. These conflicts threaten society as a whole and put its very institutions at stake. The Middle East’s wars and conflicts cause many people in the region to live in despair. When war breaks out, state institutions are forced to close their doors to the citizenry, reduce jobs and services and lead to unemployment and an increase in poverty. This snowballs into more dire psychological consequences, negatively affecting minds and thoughts. A lack of funding and opportunities leads individuals to feel they are incapable of achieving their desired ambitions and goals. Not knowing when, how or even if a conflict will end leaves individuals intimidated and frightened of the future. The psychological pain that individuals endure as a result of recurring political, sectarian, ideological, and civil wars leave one with little choice but to consider leaving his or her childhood and school memories, relatives, friends, and even customs and traditions of his or her society he or she grew up in behind for other regions away from war to search for a more decent life. Family displacement and dispersion, the suffering of children and the deterioration of economic, social and political conditions all follow from war and conflict. Here are some other consequences:

- Educators might be also forced to collect their belongings and flee when schools’ doors are closed due to war. Students lose access to more than education and role models they can emulate, they lose the desire to maintain their education.

- War diminishes the effectiveness of law in keeping societal spectra organized and regulated. In light of the law’s weakness and ineffectiveness, criminality, looting, and theft all ensue. The consequence of such criminality is a deviation from social norms, social conduct and individual civilian behavior from a correct path consistent with historical traditions and customs aligned with ethical legislation and international systems.

- Conflict and wars are major causes of the spread of deadly diseases such as Cholera among others. The international community has witnessed the spread of Cholera in Yemen beginning in 2016 due to a war whose roots political, civil and sectarian. Cholera spread rapidly through various cities due to the lack of safe, treated drinking water.

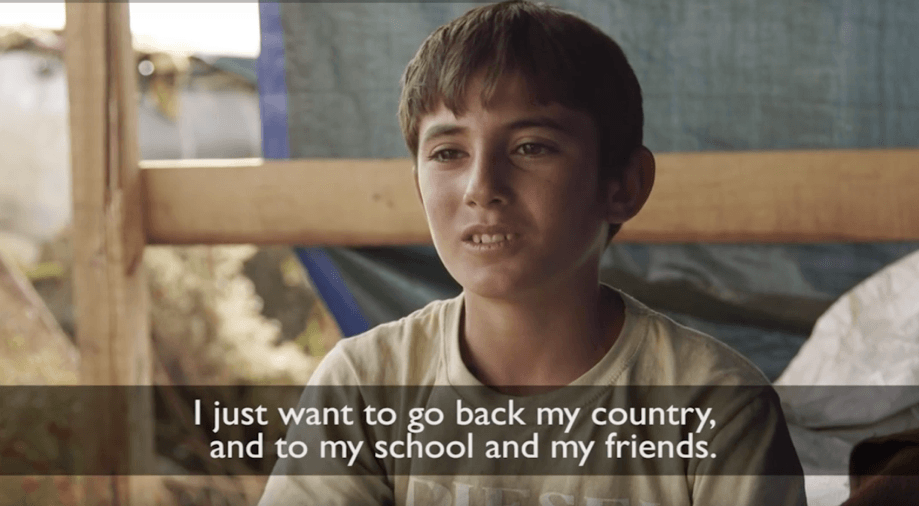

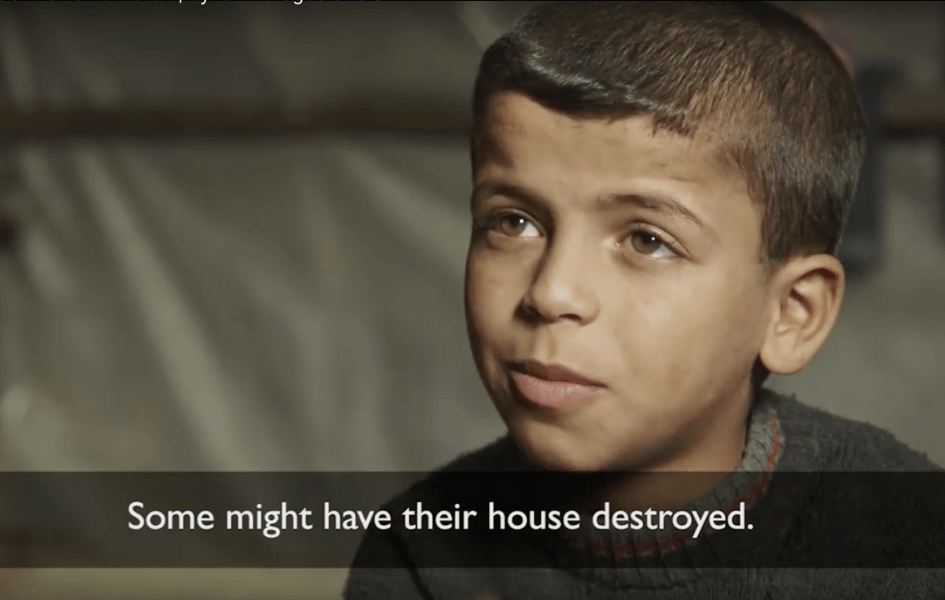

- This video shows the impact of war on children: https://youtu.be/dG8qrqCDOmU

The individual’s role in spreading a culture of peace in Middle Eastern societies:

Each individual plays an essential role in the development of society and its foundations. Each individual can be a source of energy and power for his or her society. When society sets the general goals and expected tasks that need to be achieved, it is the individual who implements them, participating in different activities to turn societal goals into reality. Every person in the Middle East, whether Muslim, Jewish, Christian or non-believer in the Abrahamic religions, male or female, is directly and indirectly linked to the security and stability of the Middle East and the world as a whole. Each individual in the Middle East must realize that he or she has great responsibilities as regards improving and building their societies. Each individual in the Middle East must also realize that he or she is the maker and source of peace and that peace is initiated from within each individual. If an individual wants to get rid of the scourge of war, if the individual wants to prevent the poisons of conflict from paralyzing society’s development, if the individual wants peace to prevail in Middle Eastern societies, then he or she must first understand the principles of peaceful societies and cultures that serve as a foundations for human coexistence.

Freedom is one of the most important principles on which a culture of peace is based. Freedom is a central and a fundamental pillar of peace and coexistence between the members of a society. We must recognize and assert that “absolute” freedom does not exist in any society in the world. We only think “absolute” freedom exists. Because “absolute” freedom can also mean “absolute” chaos and “absolute” corruption and this is unacceptable. Freedom itself does exist, but it is restricted in accordance with the agreed upon limitations of society’s values, idea, and traditions. Freedom comes in many forms. The following are some forms of freedom: freedom of expression, freedom of opinion, freedom of the press, freedom to wear the clothing you like, etc. One of the most important freedoms that must be understood thoroughly and appreciated by the individual living in the Middle East is freedom of belief and religion.

Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are the three monotheistic and Abrahamic religions that constitute an integral part of Middle Eastern history and culture. It is also worth mentioning that the three religions were born, so to say, in and around the Middle East. Although there are differences between these religions, many religious scholars conclude that the similarities between these religions are more numerous than the differences. This video explains how these three religions are connected to each other https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4xyE3ITVb6E

Because the similarities outweigh the differences, each individual in the Middle East should appreciate and glorify those similarities to pave the way for tolerance and coexistence to in turn increase cooperation and harmony between Middle Eastern societies. Individuals must respect differences between the three religions to stop the bloodshed and avoid ideological and sectarian wars. Differences in beliefs and religion should not spoil people’s relations with each other and people should not seek to eliminate a party or side that disagree with their views.

Islam and the Freedom of Religion:

There are many verses from the Qur’an, the Islamic faith’s holy book, that show the importance of respect for others’ beliefs and religion. The verses emphasize the importance of not interfering with other people’s affairs and of not forcibly imposing beliefs or religion on others. It is not the right of any person to interfere in the relationship of another person with his or her God. Everyone has the right to choose his or her own beliefs and religion. And everyone is responsible for his or her own actions. The following are some examples from the Qur’an:

“There is no compulsion in religion” The Cow: 256

“I do not worship what you worship, you do not worship what I worship, I will never worship what you worship, you will never worship what I worship, you have your religion and I have mine” The Disbelievers: 2-6

Human beings have no right to attack the beliefs of other people and the only one who can judge people is God. Human beings have the right to offer advice but without anger. Humans have the right to debate and support their arguments with proof and evidence in a calm and respectful manner. Humans have the right to express their opinions but without encroachment or assault on others. Humans do not have the right to force others to change their views and beliefs.

- ({Prophet}, call people to the way of your Lord with wisdom and good teaching. Argue with them in the most courteous way) The Bee: 125

It is crucial that we interpret and understand the verses of any religious text very carefully to determine the intended meaning. Proper interpretation requires careful study and this is not always an easy task. People should strive to embody the greatest integrity when they interpret verses of a religious text.

Organizing events, seminars, discussions, and workshops:

In order to create an atmosphere of cooperation and peace among individuals in Middle Eastern societies, to enable the individual to develop his or her interpersonal skills, and to encourage the individual to actively engage in the development of his or her society, we should organize and coordinate events, seminars, discussions and workshops that bring together individuals from different Middle Eastern communities to address important topics and instill peaceful values, principles, and behavior within every individual. Some examples of constructive topics that can be addressed through workshops include:

- Teamwork and team building

- Self and time management

- Communication and presentation skills

- Negotiation skills

- Work ethics and behavior

- The idea of peace and the role of the individual in achieving peace and tolerance

- The idea of freedom and how to carefully use freedom to build society and not to destroy it

This is just an example that shows how an individual can use his or her time wisely to contribute to society instead of wasting time in initiating conflicts with other groups of people.