As the Taliban took over Afghanistan in August, many Afghans became fearful of what life under Taliban rule would resemble. This fear prompted a wide array of Afghans from across civil society to try and flee the country before their worst fears would actualize.

Those who could flee traveled to Kabul to evacuate Afghanistan via airlift or went into neighboring states such as Pakistan While those who were lucky enough to make it out were spared from the Taliban’s reprisal killings, they still face many challenges in the new nations they find themselves in. One of the states which has become a top destination for Afghan refugees is Turkey.

Conditions Faced by Afghans

In 2021, over 40,000 Afghans made the dangerous trek into Turkey from Afghanistan. Afghan refugees within Turkey face a myriad of issues that present a critical threat to their security. One such threat that the refugees have faced on their journey has been their mistreatment by the Turkish police. This comes at a time when Turkey has seen an influx of Syrian migrants in recent years, which has resulted in a rise of anti-immigrant sentiments. Based upon reports by Rise to Peace founder Ahmad Mohibi’s trip to Turkey, only a small amount successfully make the crossing from Iran due to heightened security measures.

Another critical threat Afghans are presented with is the human smugglers who have taken advantage of their dire situation. The operations of these smugglers are often sophisticated in nature, using coded messages on popular messaging applications such as WhatsApp and Telegram. These operations demonstrate cyber capabilities, allowing them to stay ahead of law enforcement agencies of the states receiving Afghan refugees. More importantly, these capabilities allow them to endanger the lives of one of the world’s most vulnerable populations.

Furthermore, while the journey to Turkey is harrowing for many Afghans, it is simply a stopover for seeking asylum within member states of the European Union (EU). For some, the journey takes them by boat, which puts them in danger of becoming victims of drowning from boats capsizing, such as the unfortunate incident in the English Channel. For others, they have made dangerous treks through mountain ranges, such as the Alps, where they run the risk of freezing. Another route Afghans have chosen has been to cross the Bosnia-Croatia border, where they hope to claim asylum within Croatia since it is a member of the EU.

A Path Forward for Europe

Most importantly, it is imperative for the regional bloc to address this humanitarian disaster through policy. This can be achieved by states within the bloc implementing a uniform policy for the absorption of the Afghans claiming asylum. For this to happen, the states that do not care for international humanitarian law must be persuaded with a pragmatic argument presenting the threat to their security, should an uncoordinated response be the norm.

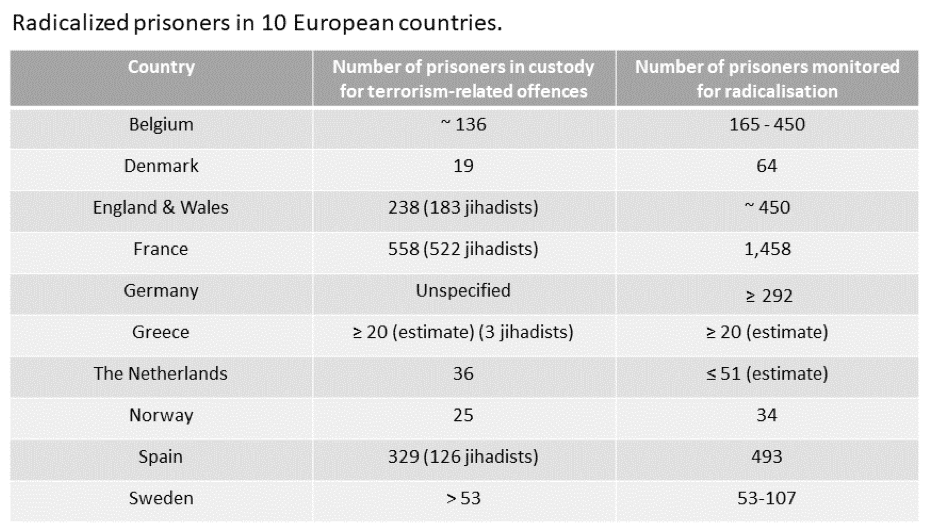

This disregard for humanitarian obligations by some EU nations is best represented by the likes of Hungary, which has refused to accept more migrants to embolden their base. The last instance of a migration crisis which the EU faced was exploited by members of terrorist organizations who posed as refugees. Should a response not be unified, they would be at risk of further exploitation by extremist organizations that capitalize upon a disorganized effort.

The EU has become a beacon for migrants due to its political stability and the opportunity for economic advancement which outpaces the states from which migrants arrived. So long as this is the case, the EU will face more waves of migration in the future. By refusing to address the issue of migration, it will ignore one of its most persistent issues for decades to come. While its adversaries may not recognize this fully, it provides the bloc with an opportunity to shore up one of its most salient challenges to its integrity.

Furthermore, resources should be made available to states which are facing the migrant crisis by other states within the bloc as well as international organizations like the UNHCR. The issue of migration has become a divisive issue among the EU, as other states are seen as taking the lion’s share without any help. This only serves to divide the EU politically and provides an opportunity for nefarious actors to pursue their interests at the expense of EU states.

The bloc must recognize the current geopolitical climate which it finds itself in and understand that it is another arena in which other powers will try to project their influence. Only by effectively managing the current crisis through solidarity will the EU protect its interests as well as its security.

Christopher Ynclan Jr., Counter-Terrorism Research Fellow