Introduction

Several high-profile terrorist attacks in Western Europe and North America in recent years have been committed by migrants from Central Asian countries, including Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. However, much of the popular discourse on foreign terror threats doesn’t include analysis of this trend. Most famously, President Donald Trump’s proposed travel ban on countries allegedly prone to radicalization mentioned nothing of Central Asia. This report reviews relevant case studies of Central Asian ‘lone wolf’ terrorism abroad in order to find commonalities and lessons from these attacks. The report also analyzes contextualized casualty comparisons of Central Asian attacks in the context of post-9/11 international terrorism. This report concludes by noting both the mixed cyber and personal nature of recruitment and training among the case studies, as well as the presence of significant intelligence failures.

Background

Since 1991, the Uzbek government has used brutal repression of a peaceful religious movement as a tool to stop the radicalization of the country’s Muslims. The Karimov regime imprisoned thousands accused of religious activity, banned imported Islamic literature, and controls the prayers and discussions in Uzbek mosques. It appeared to have worked: the country has seen little terrorist activity on its own soil since the 2000s.

However, radicalized Uzbeks and other Central Asians have since engaged in multiple instances of terrorism abroad. While this is likely due to the same radicalization and recruitment measures common to other demographics, the dual challenge for Central Asian migrants of integrating into foreign lands while being actively alienated by their own government has likely increased their susceptibility to radicalization. Moreover, some theorize that the Uzbek government’s control of domestic, Islamic voices shifted the country’s Muslims towards other, more politicized voices, including internet content which is often radical and serves extremists. Notoriously, this has occurred in Russia where tight Central Asian communities, combined with active extremist recruitment, have radicalized many guest workers. Indeed, up to 90% of ISIS foreign fighters from Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan were radicalized or recruited while living as guest workers in Russia.

There has also been a push by terrorists to especially radicalize Central Asian migrants. ISIS tailored whole sets of online recruiting and social media content toward Uzbeks, including a specialized spokesman tasked with focusing his propaganda on Central Asians.

Case Studies

Boston Marathon Bomb Attack (April 15, 2013)

Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev were born in Kyrgyzstan. In the 1990s they lived in Chechnya for a short time before returning to Kyrgyzstan due to political violence in the region. They moved to Dagestan in 2001 before gaining refugee status in the United States and immigrating. In 2011, the Russian government passed intelligence to the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in which they warned of the Tsarnaevs’ possible radicalization, and that the Tsarnaev’s mother had been added to Russia’s terrorism database. These concerns focused on a planned trip the Tsarnaevs were taking to meet with known extremists in the Caucasus. The trip occurred in 2012 when Tamerlan travelled to Dagestan and Chechnya to allegedly pick up a new Russian passport, which he never actually received. Surveilling Tamerlan and his trip, Russia even reported that he interacted with mosques known for hosting extremists. After his return, Tamerlan and brother Dzhokhar used online bomb-making instructions from the Al-Qaeda magazine Inspire to construct two improvised explosive devices. They placed the two bombs near the finish line of the 2013 Boston Marathon, detonating them 10 seconds apart. The two bombs killed three people and wounded 264.

Istanbul Nightclub Attack (January 1, 2017)

Abdulkadir Masharipov is believed to have entered Afghanistan in 2011 after leaving Uzbekistan. During the ensuing five year period authorities believe he may have received militant training in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, or Syria. In January 2016, after moving through Iran, Masharipov settled at an ISIS safehouse in Konya, Turkey. His initial orders from ISIS suggested a New Year’s Eve attack on Taksim Square, but after surveilling the area his target was switched to a nightclub. Demonstrating a high level of military training, Masharipov entered the Reina nightclub in Istanbul just after midnight on January 1st and launched a two-hour assault with an automatic rifle, killing 39 and injuring 70.

St. Petersburg Metro Bombing (April 3, 2017)

Akbarjon Jalilov was a 22-year-old ethnic Uzbek who grew up in Kyrgyzstan. Interviews indicated that he became more religious during 2014, but neither family members nor his social media activities demonstrated a link to extremist groups. In 2015, he traveled to Turkey where he may have crossed the border into Syria. On April 3rd, 2017, Jalilov entered a St. Petersburg Metro station and detonated a suicide bomb, killing 14 commuters and injuring 60. Jalilov’s attack was claimed by the Imam Shamil Battalion, a small Al-Qaeda-linked terrorist group operating in Syria.

Stockholm Truck Attack (April 7, 2017)

Rakhmat Akilov grew up in Uzbekistan but spent the four years between 2009 and 2013 as a legal, guest-worker in a Moscow cement factory. After losing that job in 2014 he moved from Uzbekistan to Sweden in search of work. The Uzbek government reported that in 2015 Akilov travelled to Turkey and attempted to cross the border into Syria, but was detained and sent home. On April 7, 2017, Akilov drove a truck into a department store in Stockholm, killing four people and injuring 15. After his attack, the Uzbek government revealed it had passed intelligence to Sweden regarding Akilov’s attempts to radicalize and recruit Uzbeks to join ISIS in Syria. He was on the Uzbek government’s suspected terrorist most wanted list . Swedish authorities admitted they had received intelligence in 2016 regarding Akilov’s possible radicalization, but that they had not confirmed its validity. Indeed, his social media accounts demonstrated several links to known extremists.

New York City Truck Attack (October 31, 2017)

Sayfullo Saipov moved from Uzbekistan to the United States in 2010, residing in an immigrant community in Ohio before moving to Patterson, New Jersey. There were few suspicions that he was radicalized before coming to the United States. His name had been on an FBI probe of a friend, but Saipov was not suspected of radicalization. Based on post-facto interviews and searches of his electronics, authorities discovered that he’d been viewing ISIS propaganda online for some time, and that he had used ISIS instructions from the internet to plan the attack. Saipov admitted that he spent a year planning the attack, and that he rented a truck to perform a test run earlier that month. On October 31, Saipov drove a truck onto a Manhattan sidewalk, killing eight people and wounding 12 – the deadliest terrorist attack in New York City since 9/11.

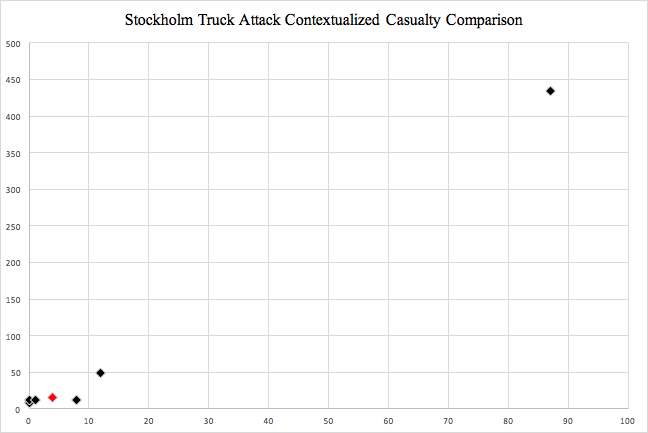

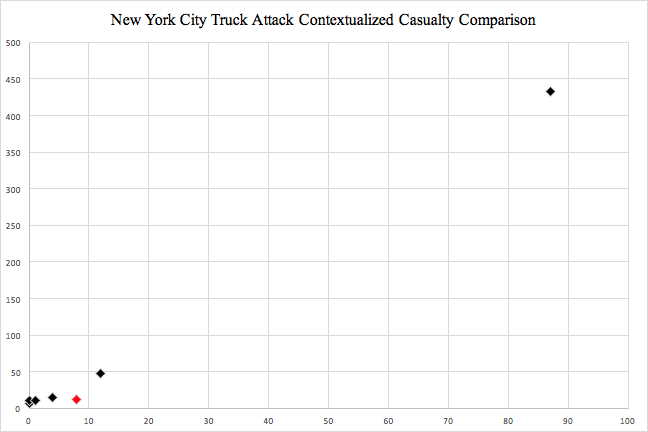

Contextualized Casualty Comparisons

This report includes visualization of the data on casualties produced by Central Asian terrorism. Due to because differences across time, location, and weapons, however, visualizing each attack across the entirety of post-9/11 terrorism data would be unlikely to yield any insights into the unique characteristics of Central Asian attacks. Thus, this report creates contextualized casualty comparisons for each attack. These comparisons visually compare attacks to other attacks that have similar weapons, locations, and timeframes in order to provide the most accurate demonstration of an attacker’s lethality versus others who performed similar actions. All data on attacks not discussed in the case study section of this report are pulled from the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) run by the Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Response to Terrorism (START). Each figure is labelled with the constraints set on attacks included in the contextualized casualty comparison. All attacks use the following search constraints: the “When” setting is set to “‘2002’ to ‘2016”, and the “Terrorism Criteria” is set to include ambiguous and unsuccessful attacks, while none of the Criteria restraints are used. All graphs display the number of killed victims along the X-axis and the number of injured victims along the Y-axis.

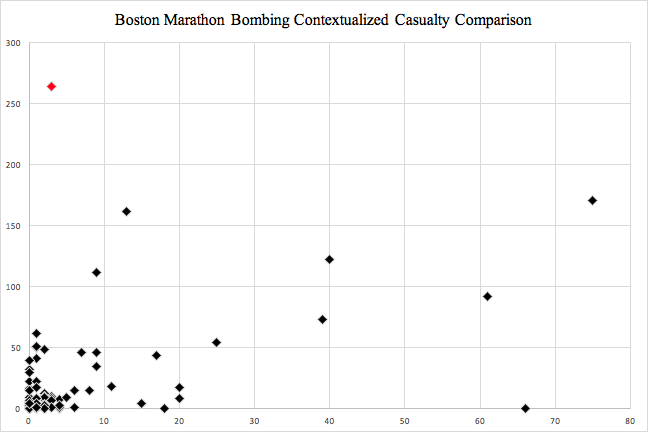

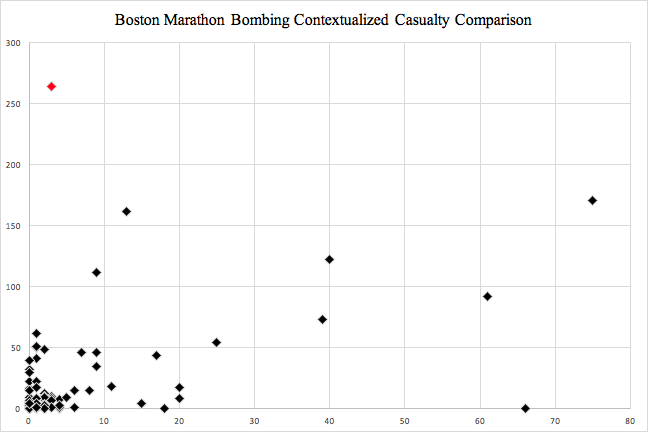

Boston Marathon Bomb Attack (April 15, 2013)

Attacks in this category had a mean of 3.739 killed and 13.124 injured. At 3 killed and 264 injured, the Boston attack placed just above the 50th percentile for killed and at the 100th percentile for injured.

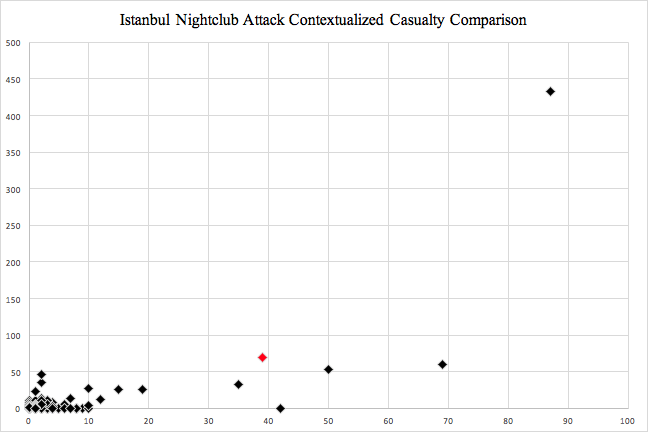

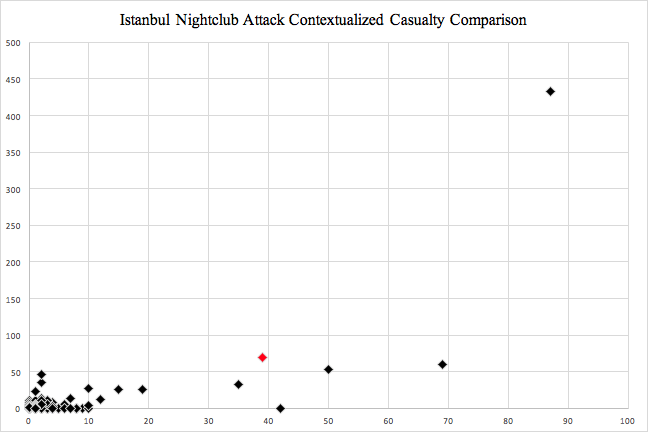

Istanbul Nightclub Attack (January 1, 2017)

The attacks in this category had a mean of 2.614 killed and 4.557 injured. At 39 killed and 70 injured, the Istanbul attack fell above the 97.5th percentile for killed and 99th percentile for injured.

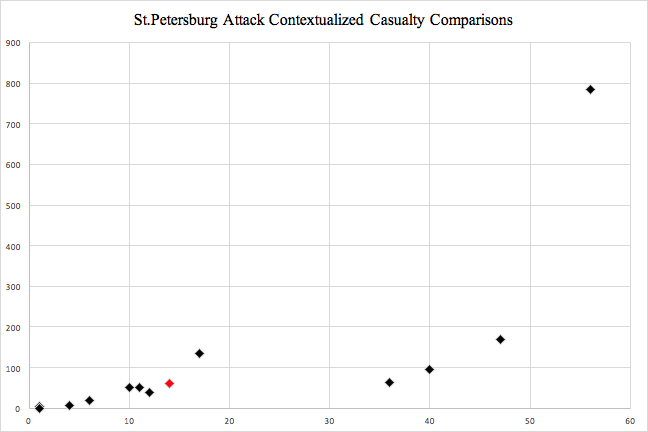

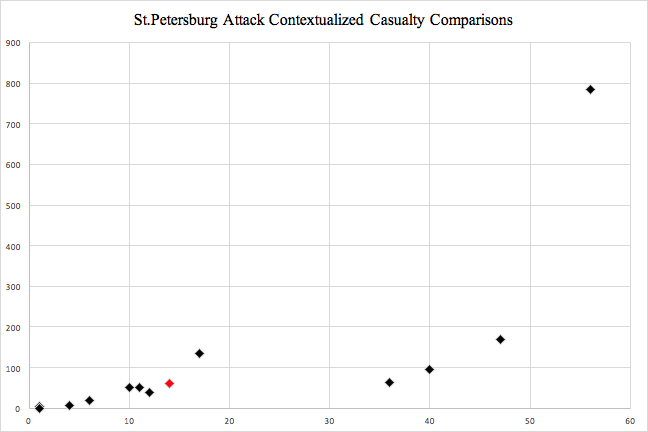

St. Petersburg Metro Bombing (April 3, 2017)

Attacks in this category had a mean of 19.615 killed and 113.923 injured. However, this was skewed by the presence of a major outlier. At 14 killed and 60 injured, the St. Petersburg attack placed just above the 50th percentile for killed and just above the 50th percentile for injured. Once the outlier was removed, the mean killed became 16.583 and the mean injured became 58.083, placing the St. Petersburg attack a bit above the 50th percentile in killed and injured.

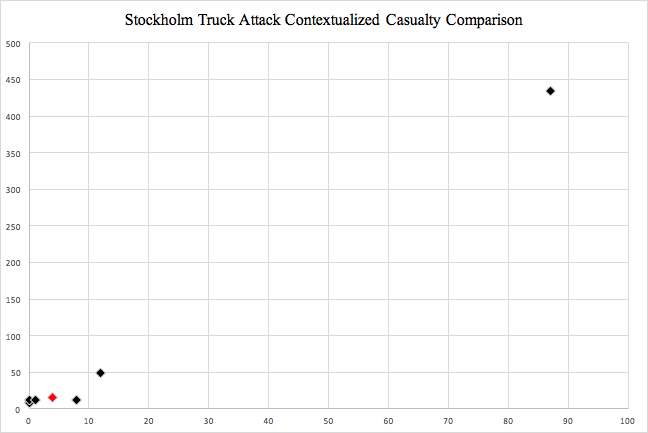

Stockholm Truck Attack (April 7, 2017)

The attacks in this category had a mean of 14 killed and 68.25 injured. However, this was heavily skewed by a major outlier. At 4 killed and 15 injured, the Stockholm attack fell just above the 50th percentile for killed and 50th percentile for injured. However, once the major data outlier was removed, the category had a mean killed of 3.571 killed and 16.143 injured, with the Stockholm attack still hovering around the 50th percentile for killed and injured.

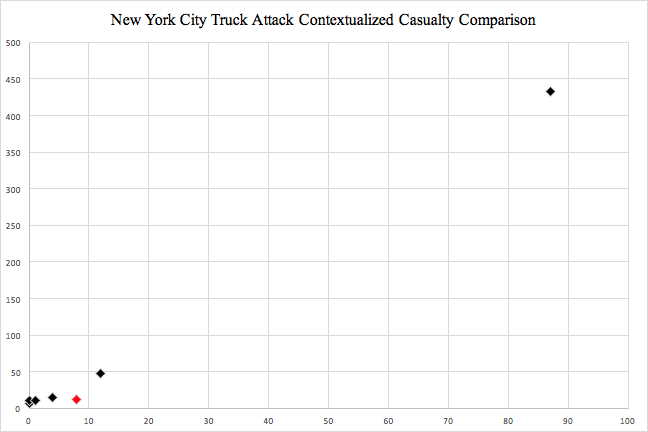

New York City Truck Attack (October 31, 2017)

The attacks in this category had a mean of 14 killed and 68.25 injured. However, this was heavily skewed by a major outlier. At 8 killed and 12 injured, the New York City attack fell just above the 50th percentile for killed and 50th percentile for injured. However, once the major data outlier was removed, the category had a mean killed of 3.571 killed and 16.143 injured, with the New York City attack still hovering around the 50th percentile for killed and 50th percentile for injured.

Conclusions

Two principle commonalities emerge from the analysis of the case studies above. First, the mix of cyber and personal recruitment and training reflects the hybrid nature of threats from non-state actors in the 21st century. While Abdulkadir Masharipov received intensive military training and was linked in to a terrorist chain of command, others never interacted with foreign militants directly and only used public information and propaganda to radicalize and plan their attacks. The use of vehicular attacks similarly exemplifies the reach of cyber-radicalization. Vehicle attacks require little expertise and are easy to coordinate from a distance, making them a central piece of ISIS’s inducement for ‘lone wolf’ attacks abroad. This problem speaks to the need for a comprehensive counter-terrorism strategy that focuses on a broader range of possible attacks rather than monolithic expectations and ‘silver bullet’ solutions.

The second principle commonality was the repeated occurence of intelligence failures. The lack of intelligence-sharing or follow-through allowed both the Tsarnaev brothers and Rakhmat Akilov to perpetrate attacks even though they’d been marked ahead of time as possible militants. Whether this was due to resource constraints, inter-governmental trust issues, inter-agency cooperation problems, or an inability to detect these threats should be the subject of further study.

The univariate analysis of the contextualized casualty comparisons for Central Asian attacks indicates that while some attacks were abnormally lethal for their methodology, region, and timeframe, many of them fit within the scope of expected casualties for their attack types. This seems to show that Central Asian terrorists are not more lethal or injurious than similar attackers.

There are several caveats to the lessons derived here. First, the case study’s sample size being so limited inherently limited our ability to draw definitive conclusions on trends among Central Asian terrorists. Second, other forms of exported terror are underrepresented in this analysis. Most notably, there’s been a substantive movement of hundreds of radicalized Central Asian fighters into conflict zones in Afghanistan and Iraq to fight for Islamic non-state actors. While this analysis purposely focused on ‘lone wolf’ attacks, this still means the analysis is about a mere subset of the foreign terror threat, rather than it’s totality.

More research and analysis must be done if the Central Asian ‘lone wolf’ is to be evaluated as a categorizable form of attack. The diversity of radicalization forms, histories, and weapons make them a difficult cohort to understand as a unified entity. However, assessment of immigration policy and immigrant experiences may shift the integration of these future militants into host societies and alter their propensity to fight against the states they enter.

Sources

[1] Laruelle, Marlene. “The Paradox of Uzbek Terror”. Foreign Affairs. Nov 1, 2017.

[2] ibid

[3] Ward, Alex. “The New York attacker was from Uzbekistan. Here’s why that matters.” Vox. Nov 1, 2017.

[4] Pannier, Bruce. “Why are Uzbeks So Often Linked to Terrorist Attacks?”. RadioFreeEurope RadioLiberty. Nov 1, 2017.

[5] ibid

[6] Ward, Alex. “The New York attacker was from Uzbekistan. Here’s why that matters.” Vox. Nov 1, 2017.

[7] ibid

[8] Radia, Kirit. “Boston Marathon Bombing Suspects’ Twisted Family History”. ABC News. April 22, 2013.

[9] ibid

[10] “Boston Marathon Bombing Timeline of key events”. Chicago Tribune. April 8, 2015.

[11] Schmitt, Eric, Michael Schmidt, and Ellen Barry. “Bombing Inquiry Turns to Motive and Russia Trip”. New York Times. April 20, 2013.

[12] “Boston Marathon Bombing Timeline of key events”. Chicago Tribune. April 8, 2015.

[13] ibid

[14] Williams, Pete and Tom Winter. “Court Documents Reveal Boston Bomber’s Statements to FBI”. NBC News. February 23, 2016.

[15] ibid

[16] “GTD ID: 201304150002”. START Global Terrorism Database.

[17] “GTD ID: 201304150001”. START Global Terrorism Database.

[18] “Istanbul Reina attacker ‘switched target’ after Raqqa order”. Hurriyet Daily News. January 18, 2017.

[19] Arslan, Rengin. “Abdulkadir Masharipov: who is Istanbul gun attack suspect?”. BBC. January 17, 2017.

[20] Istanbul Reina attacker ‘switched target’ after Raqqa order”. Hurriyet Daily News. January 18, 2017.

[21] ibid

[22] ibid

[23] “Istanbul: Victims of Reina Nightclub Attack identified”. Al Jazeera. January 2, 2017.

[24] Mirovalev, Mansur. “Russia bombing triggers crackdown on Central Asians”. Al Jazeera. May 15, 2017.

[25] Nikolskaya, Polina and Hulkar Isamova. “Suspect in Russia metro bombing traveled to Turkey, say co-workers”. Reuters. April 8, 2017.

[26] ibid

[27] Nechepurenko, Ivan and Nail MacFarquhar. “St. Petersburg Bomber Said to Be Ban From Kyrgyzstan; Death Toll Rises”. New York Times. April 4, 2017.

[28] Mirovalev, Mansur. “Russia bombing triggers crackdown on Central Asians”. Al Jazeera. May 15, 2017.

[29] “Akilovs bror i Uzbekistan: ‘Är det sant att han erkänt?'”. AftonBladet. April 26, 2017.

[30] “Stockholm attack: who is suspect Rakhmat Akilov?”. BBC. April 10, 2017.

[31] “Uzbekistan says told West that Stockholm attack suspect was IS recruit”. Reuters. April 14, 2017.

[32] Habib, Heba, and Griff Witte. “‘Sweden has been attacked’: Truck crashes into Stockholm store, killing 4”. Washington Post. April 8, 2017.

[33] “Uzbekistan says told West that Stockholm attack suspect was IS recruit”. Reuters. April 14, 2017.

[34] ibid

[35] ibid

[36] “Stockholm attack: who is suspect Rakhmat Akilov?”. BBC. April 10, 2017.

[37] Rosenberg, Eli, Devlin Barrett, and Sari Horwitz. “SayfulloSaipov’s behavior behind the wheel of an empty truck raised suspicion before attack”. Washington Post. 1 Nov, 2017.

[38] Ward, Alex. “The New York attacker was from Uzbekistan. Here’s why that matters.” Vox. Nov 1, 2017.

[39] Rosenberg, Eli, Devlin Barrett, and Sari Horwitz. “SayfulloSaipov’s behavior behind the wheel of an empty truck raised suspicion before attack”. Washington Post. 1 Nov, 2017.

[40] “Who Is Sayfullo Saipov, New York City terror attack suspect?”. Cox Media Group. Nov 2, 2017.

[41] Rosenberg, Eli, Devlin Barrett, and Sari Horwitz. “SayfulloSaipov’s behavior behind the wheel of an empty truck raised suspicion before attack”. Washington Post. 1 Nov, 2017.

[42] ibid

[43] Region: ”Eastern Europe”, “Western Europe”, “North America”

Weapon Type: “Explosives/Bombs/Dynamite”

Attack Type: “Non-suicide attack”

Target Type: “Private Citizens & Property”

[44] Region: Amassed data from one search that utilized ”Eastern Europe”, “Western Europe”, “North America” and one that used Country: Turkey

Attack Type: “Armed Assault”, “Non-suicide attack”

Weapon Type: “Firearms”

Target Type: “Private Citizens & Property”

[45] Region: ”Eastern Europe”, “Western Europe”, “North America”

Attack Type: “Suicide attack”

Weapon Type: “Explosives/Bombs/Dynamite”

Target Type: “Transportation”

[46] Region: ”Eastern Europe”, “Western Europe”, “North America”

Attack Type: “Non-suicide attack”

Weapon Type: “Vehicle”

Target Type: “Private Citizens & Property”

[47] Region: ”Eastern Europe”, “Western Europe”, “North America”

Attack Type: “Non-suicide attack”

Weapon Type: “Vehicle”

Target Type: “Private Citizens & Property”

[48] Ioffe, Julia. “Why Does Uzbekistan Export So Many Terrorists?”. The Atlantic. Nov 1, 2017.

[49] ibid