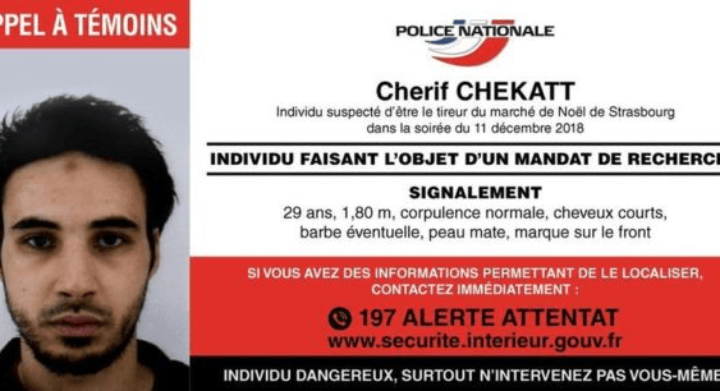

Cheriff Chekatt, the Strasbourg attacker. Image credit: BBC.

At approximately 8 pm on December 11th, 29-year-old Cheriff Chekatt opened fire in a crowded Christmas market in Strasbourg, France, killing and injuring numerous people in a premeditated act of terror. Not only did Chekatt manage to kill and wound numerous individuals, he was also able to evade authorities for two days before being shot and killed by police- despite the fact that, even before the attacks, Chekatt was already under surveillance (BBC News, 2018).

To understand why this attack was not prevented and why authorities were so slow to halt Chekatt’s rampage, this article will discuss the perpetrator’s background, examine the facts of the case, and outline what implications this attack has for the French government, the public, and others around the world.

Chekatt was born in Strasbourg in 1989 and has an extensive criminal history. He has 27 convictions for crimes, including robbery, in France, Germany, and Switzerland. Authorities believe he was radicalized in prison. They placed him on the “fiche S” in 2015, which is a watchlist monitored by the General Directorate of Internal Security, France’s primary domestic intelligence agency (BBC News, 2018).

The people placed on this watchlist represent potential threats to national security, so Chekatt’s placement on this list begs the question as to why he was able to carry out this attack while being monitored by the DGSI.

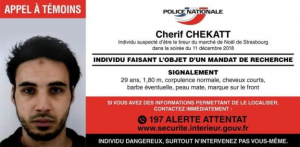

The route taken by Chekatt throughout the attack and its aftermath. Image credit: BBC.

The attack itself took place in several locations. Chekatt remained constantly on the move to confuse authorities, using the Christmas market crowds as cover. The initial attack took place in Kléber, one of Strasbourg’s central squares, which is located near the main Christmas market area. He then moved onto the rue des Grandes Arcades, rue de Samon, rue des Chandelles, and rue Sainte-Hélène, until ultimately arriving at rue du Pont Saint-Martin.

During the attack, Chekatt used a gun and knife to wound and kill people while shouting “Allahu Akbar” (“God is greatest” in Arabic) before arriving at Neudorf District via taxi (BBC News, 2018). Soldiers of the anti-terror Sentinelle operation had engaged Cheriff during his rampage, but only wounded him in the arm, enabling him to make it to a taxi and escape to the Neudorf district.

After learning he had disappeared in the Neudorf district, authorities launched a massive operation at approximately 7:30 pm on the 13th of December to apprehend Cheriff. At approximately 9 pm local time, police located Cheriff, who was trying to access a building but could not get in. After noticing authorities, Cheriff promptly fired upon them before being shot and killed. He had been carrying a gun, ammunition, and knife.

In his flat, authorities discovered a defensive grenade, loaded rifle, and four additional knives. The French government deemed this attack an act of terror, and so far there has been no news as to whether Chekatt was a member of a designated terrorist organization.

This case holds many implications for French security measures and public safety. First, while the suspect managed to kill at least three people and wound about twelve others, the attack could have been much worse had the French authorities not prepared emergency evacuation plans.

Because of this, the streets were cleared relatively quickly by authorities, and lives were undoubtedly saved because of it. However, this case also illustrates how difficult it is for authorities to track down a single assailant in a crowded area with thousands of people moving around.

Terrorist attacks at crowded events during the holidays are also not abnormal. For example, the truck attack in Berlin in December 2016 also occurred at a populated Christmas market. The primary implication to take from this is that the general public, not just in France but in every country around the world, must practice extreme vigilance when attending crowded gatherings in populated areas, especially during the holidays.

These gatherings are prime targets for lone-wolves and organized terrorist organizations who see these events as opportunities to inflict mass casualties.

The public should not become solely dependent on local law enforcement and other authorities, but should prepare ahead of time in the case a crisis does unfold to protect themselves, family, friends, and others.

This preparation can include conducting research on certain areas ahead of time, planning potential evacuation routes, and compiling an emergency kit made up of first aid, flashlights, water, and other provisions.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency provides an in-depth guide on how to prepare for potential crises ranging from natural disasters to terrorism.

Proper preparation can mitigate the number of fatalities and fallout from these attacks.