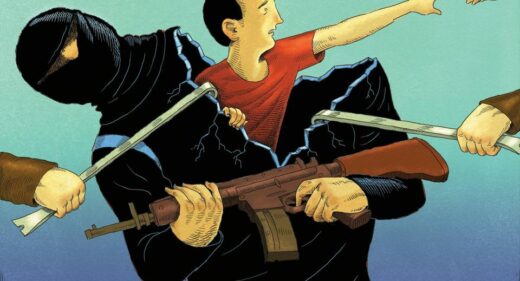

Twin terrorist attacks targeting Burkina Faso’s army headquarters and the French embassy shook the country’s capital, Ouagadougou on March 2nd (Associated Press). The attacks were conducted by two groups of men, each with 4 to 5 people, and left 30 dead (including nine perpetrators) and 85 wounded. According to the International Crisis Group, “The attacks represent an alarming escalation for Burkina Faso in terms of organization, lethality of armaments and length of engagement,” (BBC). Symbolic locations in the capital were chosen as they represent power and authority to terrorist groups throughout the region. The attacks have heightened concerns about Burkina Faso’s increased jihadist violence.

The attacks appeared to be coordinated. One set of men drove to the army headquarters’ main entrance. Using a rocket-propelled grenade they made their way through the front gate. Inside the complex, a second vehicle packed with explosives hurtled toward the headquarters’ main building, at which point it detonated, causing damage not only to the building but also to the infrastructure surrounding it. The attackers then opened fire on military personnel near the main building’s courtyard. Reports have been confirmed by French and Burkinabe forces. Measures have been taken to heighten security around the complex but more measures are in order to secure additional terrorist targets throughout the country.

A group of attackers tried to enter the French embassy but were repelled. They then shifted positions, encircling the embassy and exchanging fire with Burkinabe security forces. Burkinabe forces were supported by French military personnel, who in turn, had been deployed by helicopter around the building. The ensuing gunfight lasted several hours. French support was crucial to the local security force’s defense. According to a French military source, “Burkinabé forces were crushed at the beginning. We helped them,” (Depagne). According to Rinaldo Depagne, West Africa Program Director at The International Crisis Group, despite that Burkinabe forces were unable to counter the assailants on their own, “…compared to the previous two attacks in Ouagadougou in 2016 and 2017, the response time and organization of the reaction seem slightly improved.” Burkinabe security forces would benefit from additional training from international forces in the area in order to be more effective should a similar attack unfold in the future.

AFP PHOTO / Ahmed OUOBA (Photo credit AHMED OUOBA/AFP/Getty Images)

Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin claimed responsibility for the attack the next day, March 3rd. JNIM, or, translated to English: The Group to Support Muslims and Islam, aka GSIM, is an al-Qaeda affiliate in the Sahel region, comprised of formerly disparate jihadist groups including Ansar Eddine, al-Mourabitoun, and the Macina Liberation Front. JNIM’s leader, Iyad ag Ghali, said the attack was retaliation for French military airstrikes on February 14th. During that attack, a number of JNIM’s leaders, including the deputy of Mourabitoun, al-Hassan al-Ansari, and Malick ag Wanasnat, an ag Ghali confidant, were killed. That mission was part of an increased effort by Malian armed forces (FAMA) working closely with French counter-terrorism, aka The Barkhane, in support of the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA).

Burkina Faso has experienced a spate of terrorist attacks since experiencing a coup in 2015. Notably, in January 2016, 30 people were killed in the capital by an attack claimed by Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). On August 13th, 2017 jihadists shot up a Turkish restaurant in the capital killing 19 and wounding 25. Areas in the country’s north, along its border with its unstable neighbor, Mali, have also seen jihadist violence. Many of the attacks have been conducted by Ansarul Islam, a local Islamist group with working ties to jihadist organizations in Mali.

Burkina Faso’s security forces deteriorated following the departure of President Blaise Compaoré in October 2014, rendering them incapable of repelling attacks like those on March 2nd. According to Burkinabe sources, the army has become disorganized. The Presidential Security Regiment (RSP), Burkinabe’s special forces, were dismantled and have not been replaced since the president left. According to the International Crisis Group, “Intelligence gathering appears to be weak, judging by the failure to detect or disrupt the major attacks that happened on Friday. Two teams totaling at least eight men were able to cross the city center carrying heavy weapons and driving a car full of explosives without being spotted,” (Depagne). Burkinabé authorities suspect members of their own army leaked vital information, aiding the attackers. Military attaches under President Compaore’s leadership, including spymaster Gilbert Diendéré, had been in charge of a comprehensive, international intelligence network that was quite effective. Key counterterrorism structures have not been replaced since their departure.

Steps have been taken to operationalize the G5 Sahel Joint Force, supported by France plus Burkina Faso and four of its neighbors. Military officials claim task force meetings were in progress when the attacks occurred. The attacks, in fact, may have been aimed at discouraging the mobilization of the G5 Sahel Joint Force.

Failure to address security challenges in Burkina Faso could lead to the intensification of an already complex regional conflict. The international community, including organizations like the United Nations, should cooperate to prevent the country from falling further into violence and instability. Cooperation to implement such efforts and foster stability in the region has worked in the past. It can work today and in the future as well.

Sources:

- Depagne, Renaldo. “Burkina Faso’s Alarming Escalation of Jihadist Violence.” Crisis Group, ICG, 7 Mar. 2018, www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/burkina-faso/burkina-fasos-alarming-escalation-jihadist-violence.

- “Burkina Faso Attack: French Embassy Targeted in Ouagadougou.” BBC News, BBC, 2 Mar. 2018, www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-43257453.

- Press, Associated. “Burkina Faso Authorities Arrest 8 after Jihadist Attacks.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 6 Mar. 2018, www.washingtonpost.com/world/africa/burkina-faso-authorities-arrest-8-after-jihadist-attacks/2018/03/06/6dd16370-2164-11e8-946c-9420060cb7bd_story.html?utm_term=.85043c6874e5.