[gview file=”http://www.risetopeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Special-Report-04252.pdf”]

The 40-year Afghan War and the Everlasting Hope for Peace

Security forces run from the site of a suicide attack after the second bombing in Kabul, Afghanistan, Monday, April 30, 2018. A coordinated double suicide bombing hit central Kabul on Monday morning, (AP Photo/Massoud Hossaini)

Today marks the 40-year anniversary of the Afghan civil war. A country at war for four decades, Afghans continue to have faith that peace is possible.

The people are tenaciously hopeful, but for how long, given the unstable environment and competing for socio-political agendas? Terrorism continues to rise, and the democratic process is under fire. Just last week, more than 60 men, women, and children in Kabul and Baghlan province were killed in the voters’ registration attack. The following chronological framework of the Afghan Civil War may provide some perspective into this complex country turmoil and its psyche.

Outside the presidential palace gate (Arg) in Kabul, the day after the Saur revolution on 28 April 1978

In 1978, The People’s Democratic Party, a political party in Afghanistan backed by the Soviet Union, attacked the presidential palace. The party killed the first president of Afghanistan, Sardar Mohammad Daoud Khan, and his entire family. Then, the Party took the throne. The People’s Democratic Party would remain in power for 14 years while fighting the U.S.-backed Afghan Mujahideen, a rebel group of freedom fighters that stood against the communist regime.

United States, Afghan Mujahideen, France, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and other allies fought against the Soviets in Afghanistan. In the proxy war between the East and West, the West came out the winner and the Soviets subsequently lost the fight in Afghanistan. In 1989, the last of the Soviet troops pulled out, but the civil war continued as the Afghan Mujahideen set their sights on the last communist president of Afghanistan, Mohammad Najibullah.

Soviet Army soldiers wave their hands as their last detachment crosses a bridge on the border between Afghanistan and Soviet Uzbekistan, Feb. 15, 1989.

In 1992, although the Mujahideen declared victory, a devastating civil war followed. From 1992-1996, Afghanistan experienced one of the most destructive civil wars in its history. Afghans often refer to it as the “Bloody War”. The Afghan Mujahideen did not compromise on a shared power by a unified government. Instead, fought for the throne, and like Syria resulted in a devastated Afghanistan. The most perilous party was the Hezbi Islami, meaning Islamic Party, led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, also known as the “Butcher of Kabul”. Hekmatyar’s missiles killed thousands of innocent residents of Kabul. According to the Human Rights Watch, by the year 2000, roughly 1.5 million people died as a direct result of the conflict, and some 2 million people became permanently disabled.

In 1996, as the Mujahideen fought for power, the Taliban (“students” in Arabic) emerged in Pakistan. Backed by the Saudis and Pakistan, the Taliban seized Kabul in 1996. They introduced an extreme version of Islam, banning women from studying and working, and inflicting severe Islamic punishments upon the citizens, such as stoning people to death, public beheadings and amputations.

Afghans were struggling for deliverance when on September 11, 2001, Al-Qaeda brought down the World Trade Center in an attack that killed more than 3,000 innocent Americans. That was the year that the United States declared a War on Terror and entered Afghanistan. Since then, the U.S. has remained, combating terrorism to build democracy and help bring more peace to the country. Despite the U.S.’ long tenure in Afghanistan, the same challenges exist.

Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s bombardment of Kabul during the 1990s inflicted some of the worst damage in more than 40 years of war, destroying one-third of the city and killing tens of thousands of civilians.

Afghanistan is not an easy fix. Afghans are ready for a democratic change in order to bring more peace to their homeland, but establishing democracy requires time. The question remains as to whether the government is ready to hold a transparent election because Afghans are so tired of war. In fact, most Afghans are willing to give up almost everything, including many civil liberties, in exchange for a semblance of peace in their homeland. It is hopeful that, despite the failures of the government, Afghans, and particularly the young generation, the generation of war, will be able to make some traction.

Through higher education, new opportunities will present themselves to these young men and women. Armed with a level of understanding and the kind of knowledge aimed at progress over destruction, this generation will be the agents of change.

Ahmad Shah Mohibi is founder and president of Rise to Peace, and a national security expert. Ahmad Mohibi is a published writer, as well as a George Washington University and George Mason University Alumni. Follow him on Twitter at @ahmadsmohibi

© CNN Money[1]

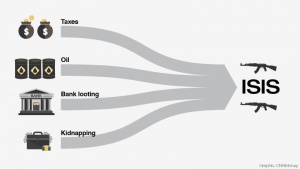

In 2015, ISIL’s annual revenue was estimated to range from $1 billion to $2.4 Billion.[2] The terror organization had a higher GDP than 60 legitimate countries. Unsurprisingly, ISIL is considered the most well-funded terrorist organization in the world.[3] Governments and law enforcement agencies must aggressively follow the money and stop the flow of financial support to reduce and ultimately eliminate terrorist conduct.

Although political and religious ideologies are often foremost in our analyses, money is primary to any terrorist attack, be it a small-scale, stand-alone attack or a large, complex operation. Terrorism operations are not always cheap. The price of an attack can range from $500, in the case of the Boston Marathon bombings, to $450,000, al Qaeda’s estimated costs for perpetrating 9/11.[4]

Terror groups leverage a catalog of methods to acquire funding. In many senses, ISIL is not doing anything new. Rather, it has succeeded in acquiring funding on a heretofore unprecedented scale for a terror organization. It continues to use traditional terrorist methods in addition to developing its own, unique means to acquire funding.

Terrorist groups exploit natural and economic resources. They operate in the vacuum created by weak and collapsed states. ISIL levied punishing taxes in territory it usurped. Terror groups are also perfectly situated to capitalize on unguarded reserves of diamonds and oil. Diamonds, in particular, are uniquely valuable and easy to smuggle. Al Qaeda reportedly traded in diamonds prior to 9/11.[5]

Oil, as is frequently the case, is the big-ticket item. Oil is the one resource that the current globalized economy cannot live without. The Middle East is rich in this precious fuel including ISIL territory in Syria and Iraq. Regardless of their lack of access to global oil markets, ISIL continues to find buyers for their black gold. ISIL allegedly made more than half of its 2015 revenue, roughly $500 million, through the sale of oil in its territory.[6]

Tried-and-true criminal operations remain at terrorists’ disposal. A mainstay of terrorist funding comes from the drug trade. The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE or Tamil Tigers) relied on narcotics trafficking, the Colombian FARC exploited the cocaine trade, and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) sought to drive out competing drug networks.[7] Ideologically, terrorists might denounce drug use as un-Islamic, but they never fail to exploit this revenue stream.

Kidnappings and ransoms remain a lucrative source of terrorism funding. Unlike the United States, Israel, and several European nations who refuse to pay ransoms, others have submitted to kidnapper’s demands. ISIL is estimated to have made between $20 to $45 million in kidnapping ransoms.[8] Kidnappings remain a mainstay of terrorist networks across the world.

Illegal second-hand markets exist as alternative avenues for illicit revenue. The Provisional Irish Republican Army engaged in arms smuggling throughout its terror reign. Hezbollah even exploited regional price differences in the United States to buy cigarettes in lower taxed states and illegally sell them at a discount in high tax states like New York. ISIL’s variation on the theme sees them plundering historical sites and selling priceless artifacts for millions of dollars.

State and non-state actors alike can provide economic support to terror networks. Before 9/11, state-sponsored terrorism was a significant concern. Libya, Iran, and Pakistan are perennially accused of funneling money to terrorist groups. Regional support is another key asset. Charities and corporations can serve as fronts to give an organization’s fiscal acquisitions a legal veneer[9]. Al Qaeda does this routinely. Since 9/11, though such criminal conduct has worsened, international condemnation and penalties have moved some state actors to chasten their public relations with terror groups.

Governments and law enforcement alike are familiar with terror organizations’ funding methods. However, shutting down the revenue flow is no simple task. Counter-terrorism forces do not have an easy time targeting natural resources such as captured oil fields without damaging assets that are invaluable to the state. Furthermore, how many generations of law enforcement have sought in vain to eliminate smuggling and drug trafficking? The needle hasn’t moved enough towards a cessation.

Terrorists will innovate. They will use any means available to acquire funding. Law enforcement must be equally innovative, vigilant and nimble when it comes to eliminating these networks as they appear. Law enforcement coordination has improved since 9/11, but a lack of interagency synergy continues to impede our ability to sufficiently reduce terror funding streams. Synergy requires cooperation between all agencies monitoring illicit revenue flows, be they drug enforcement, intelligence groups, or government trade organizations.

The formidable nature of the challenge before us can be discouraging. But our commitment to shutting down illicit terrorist funding is requisite in this fight. If law enforcement could slow or prevent even one attack, the effort would have been worth it. Governments, in coordination with financial institutions, must implement tighter regulations to monitor illicit capital flows and aggressively continue to shut down lucrative criminal activities.

Sources:

[1] Pagliery, Jose. “Inside the $2 Billion ISIS War Machine.” CNNMoney, last modified -12-06T03:04:34, accessed Mar 21, 2018, http://money.cnn.com/2015/12/06/news/isis-funding/index.html.

[2] Daniel L. Glaser, testimony before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Terrorism, Nonproliferation, and Trade and House Committee on Armed Services Subcommittee on Emerging Threats and Capabilities, June 9, 2016b; Center for the Analysis of Terrorism, ISIS Financing 2015, Paris, May 2016.

[3] Nicholas Ryder (2018) Out with the Old and In with the Old? A Critical Review of the Financial War on Terrorism on the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 41:2, 79-95, DOI: 10.1080/1057610X.2016.1249780

[4] Nicholas Ryder, Out with the Old and In with the Old? A Critical Review of the Financial War on Terrorism on the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant, 80-81.

[5] Terrorist Financing: U.S. Agencies should Systematically Assess Terrorists’ use of Alternative Financing Mechanisms: United States. General Accounting Office,2003.

[6] Maruyama, Ellie and Hallahan, Kelsey, “Following the Money: A Primer on Terrorist Financing,” Center for a New American Security, last modified June 9, accessed Mar 16, 2018, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/following-the-money-1.

[7] Clarke, Colin P., “Drugs & Thugs: Funding Terrorism through Narcotics Trafficking.” Journal of Strategic Security 9, no. 3

(2016): 1-15. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.9.3.1536

[8] Clarke, Colin P., Kimberly Jackson, Patrick B. Johnston, Eric Robinson, and Howard J. Shatz. Financial Futures of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant: Findings from a RAND Corporation Workshop. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2017. https://www.rand.org/pubs/conf_proceedings/CF361.html. Also available in print form.

[9] Michael Jacobson (2010) Terrorist Financing and the Internet, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 33:4, 353-363, DOI: 10.1080/10576101003587184

© LA Times-FBI Agents in Austin, Texas worked from one blast to another to capture serial bombing suspect Mark Anthony Conditt

Last week our attention turned to Austin, Texas as it suffered a series of bombings. Authorities have been hesitant to define bomber Mark Anthony Conditt or his deeds. You can bet questions regarding his intent are foremost among those investigators are trying to answer. Was this terrorism? Hate-crimes? Or was Conditt just a, “…very challenged young man,” as Austin police-chief Brian Manley said? [1]

Many would see bombings like his as acts of terror and they would identify Conditt as a terrorist. Law enforcement has been reluctant to use these words. Let’s make this simple as can be: Merriam-Webster defines terrorism as, “…the systematic use of terror especially as a means of coercion.” [2] A terrorist, unsurprisingly, is, “…an advocate or practitioner of terrorism as a means of coercion.” These definitions are tautologies, but they are as straight-forward as they come. The U.S. Code of Federal Regulations defines terrorism with a bit more nuance, “…the unlawful use of force and violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives.” [2]

My Rise-to-Peace colleague, John Sims, aptly pointed out in the wake of the Parkland shooting that the FBI sees terrorism, first, in one of two categories: domestic or international. Next, what’s noteworthy is that terrorism, “…is not a standalone criminal charge,” but one used to determine how government resources and personnel will be allocated. [2]

Key political staff, such as White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders, have avoided calling Conditt a terrorist. Secretary Sanders tweeted there was, “…no apparent nexus to terrorism at this time.” [3] Greg Abbott, the governor of Texas (R), similarly refrained from referring to Conditt as a terrorist and said, “The definition of a terrorist is tied to the mindset of the person who committed the crime.” [3]

Are the definitions themselves, or the bureaucratic actions such words trigger, the reasons we haven’t deemed Conditt a terrorist? Were the events done as a means of coercion and in furtherance of political or social objectives? The investigation remains in its infancy so it’s too soon to tell whether Conditt was or was not politically motivated. Authorities were quite transparent about locating a 25-minute video on Conditt’s cell-phone of Conditt himself explaining how he made his bombs. Was there more to the video? Austin police-chief, Manley said, “We are never going to be able to put a rationale behind these acts.” [4] At this early stage, why does he seem so sure?

© Getty Images- Serial-bomber Mark Anthony Conditt, 23, left two dead and four injured after a series of attacks in Austin, Texas

© Getty Images- Serial-bomber Mark Anthony Conditt, 23, left two dead and four injured after a series of attacks in Austin, Texas

There will be those who see Conditt as a terrorist until they are shown otherwise. My Rise-to-Peace colleague, Maya Norman, pointed out, semantics matter: How we define politically-charged terms and why matters. As permutations of violence in our midst seemingly undergo a weekly mitosis, we must be fair about how we’re defining each act and why.

Sources

- https://www.cnn.com/2018/03/22/us/terrorism-definition-trnd/index.html

- https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/terrorist

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2018/03/22/austin-bomber-challenged-young-man-or-terrorist/?utm_term=.8d2a8f412f53

- https://nypost.com/2018/03/21/austin-bombing-suspect-left-25-minute-video-confession-cops/

Source: www.voanews.com

In Canadian journalist Jay Bahadur’s film, The Pirates of Somalia, Bahadur travels to Puntland, embedding himself in a world known to few Western journalists. Oscar contenders have little to fear from Bahadur’s release, but The Pirates of Somalia does something remarkable: it gives us a naturalistic impression of Somalis as friendly and welcoming people and it shines a light on the rationale some give for turning to piracy.

It goes without saying that violent solutions to grievances should never be condoned, but contextualizing the behavior of Somalis who turn to attacking ships and taking hostages does prove enlightening. For instance, it was 1991 when Somalia last had a functioning government. The country has staggered on as a lawless, failed state for the last 26 years. One consequence is that the waters off its coast have been treated like an international cornucopia, with, “…fishing fleets from around the world illegally plundering Somali stocks and freezing out the country’s own rudimentarily-equipped fishermen.”

This report asserts that more than $300 million worth of seafood is stolen from Somalia’s unprotected coast by illegal trawlers every year. Not only are the waters overfished, but Somali fishermen don’t have the resources to compete with technologically advanced, large-scale fishing vessels. What’s striking is that while some reports say pirates are often former fishermen, many actually are not. In fact, some are simply poor people capitalizing on the misfortune of their anarchic and economically hemorrhaging state. While honest, hard-working people may be easier to forgive for turning to profitable, but illegal activities, both they and their non-fishermen compatriots reveal two iterations of one problem: Somalia can’t protect itself or an industry its people need to survive.

A NATO-led effort has reduced piracy in recent years, however, problems remain. Could the very thing that led to piracy also be its solution? According to PBS, “Access to domestic and international markets could change lives. But to sell fish internationally, Somali fishermen will have to raise their standards.” The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization is taking a stab at a solution by building a fish processing plant, though it is not operational yet. Changes are required to allow fish to sell in out-of-state markets, but such changes are achievable in the near future.

The Pirates of Somalia could have brought us deeper into the history of Somalia and the intricacies of the lawless coastal waters that resulted in overfished seas. But it succeeds in showing us that not all Somali pirates are what many think – violent, greedy men hoping to grab treasure for their chest. A deeper look into this enduring problem shows the solution, like that of many dilemmas, lies in addressing its root cause. Too often we get so bogged down in debating the nuances of a volatile issue that prescribing a solution takes many, unnecessary years. The solution to the piracy predicament in Somalia could really be something quite straight-forward: fish.