Many things changed in the United States following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Changes in law, policy, and security were made not only in the United States but around the world, in order to tackle the growing threat of terrorism. In response to these attacks, the United States government launched a military campaign called the “War on Terror.” This led to the enactment of many laws for law enforcement agencies to protect against terrorist activities.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Department of Justice, and the Department of Homeland Security are just some of the law enforcement agencies that are effective in combating terrorism. However, there is a major flaw in their combating measures. This is their improper use of racial profiling used to address national security and public safety concerns. Racial profiling is wrong and has been proven to be a very ineffective measure for preventing terrorism.

The post-9/11 era has seen racial profiling of people perceived to be Muslim in the U.S. through many different factions. This has included airport profiling, surveillance of Muslim communities, detention, deportations, special registration of immigrants, and much more. Many American Muslims have been treated as potential terrorists based on their faith alone. Following the attacks, law enforcement agencies detained over a thousand Muslims in the United States, both citizens, and noncitizens, while the government figured out whether they had any connection to the attacks.

This blatant racial and religious profiling went on for years. The first step to try and prohibit this was in 2003 when the Department of Justice issued guidelines prohibiting racial and ethnic profiling in most law enforcement contexts. According to the guidelines, profiling is ineffective because it is “premised on the erroneous assumption that any particular individual of one race or ethnicity is more likely to engage in misconduct.” These guidelines also emphasize that race-based assumptions in law enforcement “perpetuate negative racial stereotypes that are harmful to our rich and diverse democracy, and materially impair our efforts to maintain a fair and just society.”

Shortly after his inauguration, President Joe Biden reversed former President Donald Trump’s Muslim Travel Ban. This ban was an executive order that prevented individuals from primarily Muslim countries, and later, from many African countries, from entering the United States. It was seeking to keep out or deport people perceived to be Muslim based upon the racist assumption that “they” are violent potential terrorist enemies of the U.S. nation. There are solutions to improve this major flaw through more intense and reconstructed training as well as implementing new policies for all law enforcement agencies.

The next step that can be taken is for Congress to pass the End Racial and Religious Profiling Act which was most recently introduced as part of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act. This Act would prohibit federal, state, and local law enforcement from targeting a person based on actual or perceived race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, gender, gender identity, or sexual orientation without trustworthy information that is relevant to linking a person to a crime. These measures would help demonstrate to the many diverse communities in our nation’s commitment to protecting national security based on facts rather than on bias.

It is so important now than ever before, to change racist, common sense ways of thinking about Arabs, Iranians, Afghans, and anyone perceived to be connected, in one way or another, to the idea of a “Muslim terrorist threat.”

The Long Road Ahead

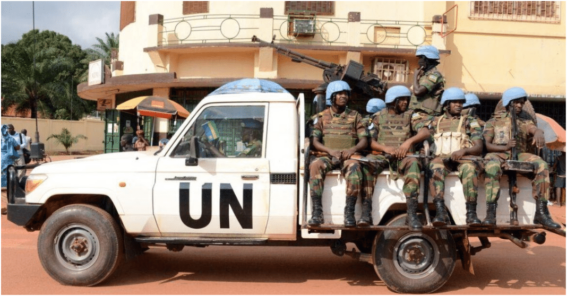

The UN’s peacekeeping operation in Mali faces an uphill battle to stabilize the country, made even more difficult by recent events. The peace that this operation hopes to keep stems from a 2015 peace agreement between northern Tuareg and Arab rebels and the government of Mali. But the civilian government was deposed in an August 2020 coup, hampering mission goals and further destabilizing the country. This article highlights three challenges to the mission mandate and how best to respond to them.

The United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), established in April 2013 by Security Council resolution 2100, has become the UN’s most dangerous current peacekeeping operation. To date, there have been 253 fatalities out of the 15,209 authorized personnel in-country. On April 2nd, four peacekeepers were killed and nineteen wounded in a direct assault on their camp in Kidal region. Significant challenges abound for this mission aiming to implement its transitional roadmap and seven-part mandate. Its main goal since June 2015 has been safeguarding and implementing an Algiers peace agreement signed between the government and the Coordination of Movements for Azawad (CMA) rebel coalition. Further complications come from jihadist insurgents such as Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), as well as brutal communal violence in central Mali. Understanding these hurdles, concrete strategies must follow.

Dual Military Coups

The most immediate challenge facing MINUSMA’s mandate is the August 2020 coup, which saw the resignation of President Keïta and Prime Minister Cisse after they were detained by the Malian Armed Forces. On January 18th, 2021, the military junta’s transitional National Committee for the Salvation of the People (CNSP) was disbanded, with interim president Bah Ndaw supervising an 18-month transition back to civilian rule. This promise of civilian rule gave cause for optimism, but the second coup in late May saw the removal of Ndaw by Colonel Assimi Goïta, who also organized last year’s coup. Goïta has since become Mali’s new president while maintaining that elections and the release of Ndaw and his prime minister will eventually occur.

Both coups have demonstrated the militarization of politics and the weakness of government legitimacy in Mali, and have significantly undermined item 2 in MINUSMA’s mandate; to support “national political dialogue and the electoral process.” Though protestors before and during the first coup had been calling for Keïta’s resignation due to economic woes and ongoing violence, a coercive resolution to an unpopular administration undermines national stability. Credibility has been damaged twice now among key allies of both Mali and MINUSMA, with the African Union (AU) suspending Mali twice, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) imposing sanctions for the first coup, the United States cutting off military aid, and the UN Security Council condemning the military’s actions all throughout.

Close coordination with the government in Bamako is required for MINUSMA’s continued operation. Mission policymakers have the unenviable task of cooperating with the self-preservationist military regime while simultaneously upholding item 1’s ideals of “constitutional order, democratic governance, and national unity.” The strategy moving forward must be one of continued pressure on and agreement with Goïta’s government on the timeline and specifics of a transfer back to civilian rule. The real power brokers in Mali must be identified and engaged, and the UN must not be satisfied with easy promises from the military. Together with AU, EU, and US partners, MINUSMA’s liaisons must extract from the military firm dates for elections and guarantees that they will be “inclusive, free, fair, and transparent,” as per the mandate.

Protection of Civilians

Alongside the tragic loss of 253 UN peacekeepers since 2013, MINUSMA has also witnessed a great deal of civilian casualties in areas outside of government control. Peacekeepers have been patrolling and expanding social services in these areas, in line with items 1 and 3 of the mandate; supporting “reestablishment of State authority throughout the country” and “protection of civilians and United Nations personnel.” But as peacekeepers navigate deadly improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and ambushes, the multitude of violent actors, vast expanses of contested land, and complicated communal dynamics have allowed thousands of civilian casualties to slip through their fingers since 2013. Atrocities and possible war crimes have been well documented, further driving a wedge between hostile communities in central Mali. This continued violence against civilians undermines mission legitimacy and the 300+ development projects it has carried out.

Protecting civilians is often an issue of policing. Protecting them from separatists requires greater policing of the vast, contested northern regions, while population centers must be protected from jihadists. Communal violence in central Mali must be lessened by policing the boundaries between feuding communities. The number of police on mission should be increased, as MINUSMA has a 13-2 split of soldiers and police. More importantly, peacekeepers should step up technical assistance and recruitment drives for local police; this is a classic method to build peace and is included in the mandate.

A new, complex frontier in peacekeeping

The final challenge concerns a relatively important shift in UN peacekeeping doctrine. Of sixteen active UN missions, MINUSMA is the only one authorized to conduct counterinsurgency. Its mandate allows it to use “all necessary means… [to] deter threats and take active steps to prevent the return of armed elements to those areas.” Resolution 2164, an update to the mission, identified “asymmetric threats” as spoilers of peace; military jargon for insurgent groups. This has created challenges on the ground and great debate in the policy world. Strategically, peacekeepers appear not to have been deployed to keep the peace, but to reach peace through force, conducting counterinsurgency alongside France and the G5 Sahel (soldiers from Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger). Tactically, counterinsurgency requires specialized training and equipment, two things that are far from standardized or even guaranteed in the UN system. Mission effectiveness is hampered by the unique challenges and confusions presented by this dissonance between peacekeeping and counterinsurgency. And with France recently announcing the end of its eight-year campaign in the Sahel, now is the time for MINUSMA to take up the mantle with clear and confident policy.

Any good counterinsurgency must clearly lay out its strategy. An understanding of the insurgents and of one’s own capacities is essential in choosing how to train soldiers and allocate resources. The 9 experts on-mission and 514 staff officers need a proper division of labor and understanding, including programs for intelligence, search-and-destroy, and public relations. All of this can only come from a unified, top-down doctrine. That is why this new arena for UN peacekeeping needs a field handbook that systematically demarcates tactics and limitations of action. This also lowers MINUSMA’s high death rate: training troops not for pitched battles but for countering IEDs and ambushes is vital, as argued by former mission commander Michael Lollesgaard.

Overall, much needs to be done. Two coups in under a year, the protection of civilians, and counterinsurgency strategy must be addressed through diplomatic pressure, increased police efforts, and tactical guidance, respectively. Relative peace is not on the immediate horizon, but these strategies will push the situation in Mali in a constructive direction.

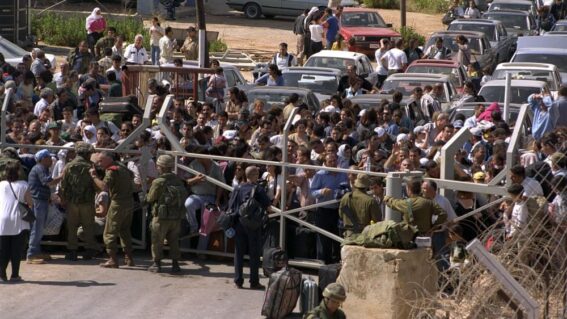

On August 15th, 2021, Taliban fighters captured Kabul without firing a shot, sending shock waves across the world and expediting the United States’ withdrawal from Afghanistan. Like the Afghanistan withdrawal, the 2000 Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon was long expected and planned. Nevertheless, the events on the ground shifted quickly and forced Israel to complete the withdrawal overnight. With events in Afghanistan still unfolding, the U.S. can learn from Israeli experiences in Lebanon and prevent a humanitarian disaster from occurring at the Kabul airport.

The Invasion

Israel and the U.S. invaded Lebanon and Afghanistan, respectively, in order to eradicate the havens these countries had become for terrorist organizations. Since the 1970s, the PLO has used southern Lebanon as a launching pad for attacks against Israel. In 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon and successfully removed the PLO from Lebanon. Israel subsequently supported the establishment of a friendly regime in Beirut led by the Phalanges.

Following its initial success, Israel withdrew from most of Lebanon and created a security zone in southern Lebanon. The military rationale underlying the establishment of the security zone was to prevent Hezbollah, another anti-Israel insurgent group, and its terror cells from entering Israel, and to deflect fire away from Israeli territory toward the IDF and the South Lebanon Army (SLA), a local militia fully funded and equipped by Israel.

Similar to the haven Lebanon provided the PLO and Hezbollah, the Taliban regime in Afghanistan provided sanctuary for Al-Qaeda. On September 11, 2001, Al-Qaeda operatives hijacked four commercial airliners and crashed them into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. On October 7th, 2001, the U.S. invaded Afghanistan and with local anti-Taliban forces routed Al-Qaeda and ended the Taliban regime. On May 1st, 2003, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld declared an end to “major combat” in Afghanistan.

The Withdrawal

For over fifteen years, Israelis believed that their presence in southern Lebanon and the casualties associated with it were necessary. As their presence drew on, however, Israeli consensus shifted, leading to broad public support for a unilateral withdrawal and the election of Prime Minister Ehud Barak, a vocal supporter of the withdrawal. Barak tried to tie his plans for a withdrawal from Lebanon to a peace agreement with Syria. But this plan failed, leading to his decision to withdraw from Lebanon unilaterally and reject the advice of his senior military leaders that advocated against it. Consequently, the withdrawal from Lebanon didn’t go according to plan and what unfolded on the ground was described as chaos.

When Israel began to transfer its military outposts to the SLA in mid-May, the SLA proved unable to hold its ground, deciding to abandon its outposts and disband rather than continue fighting. Barak had to advance the timetable for the IDF’s withdrawal from July to May 24. The collapse of the SLA and Hezbollah’s lightning advance initiated a massive flood of SLA members and their families to the Israeli border, fearing Hezbollah’s retribution.

Unlike the Israeli withdrawal, the U.S. withdrawal was an integral part of the agreement the U.S. signed with the Taliban. While the Taliban has overwhelmingly violated the agreement, President Biden remained committed to the withdrawal, ignoring the warnings of his top military generals and diplomats. Emboldened by the U.S. withdrawal, the Taliban launched its major summer offensive. Once the first provisional capital fell, the Afghan Army collapsed in days, often surrendering to the Taliban without firing a shot. On August 15th, 2021, the Taliban entered victoriously into Kabul.

Conclusions

Every day we bear witness to the unfolding events in Afghanistan. Similar events were unfolding on the Israeli-Lebanese border in 2000. Then, Israel was overwhelmed with the rapid collapse of the SLA and the flood of refugees towards its border. Israel opened its borders and allowed Israel’s allies and their families to enter Israel. Nevertheless, it took Israel 20 years to officially honor the SLA fighters and their sacrifice.

The U.S. shouldn’t wait 20 years to honor its Afghan allies. The U.S. has a moral obligation of not leaving them behind, regardless of whether they are citizens or allies. The U.S. can still do the right thing and open Kabul’s airport gates, its aircraft’s doors, and most importantly its heart, to the fleeing Afghan allies.

As the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks approaches and coronavirus is in rapid circulation, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has issued a new National Terrorism Advisory System bulletin, warning of the threat of extremist violence in the United States. This advisory is an update of the previous assessment. It is not based on any specific threat information, but rather represents the DHS’s analysis of the condition of the United States.

Coronavirus Threat

The DHS has warned local police departments that opposition to another pandemic-related lockdown policy could constitute a “terror threat.” However, this new advisory is “not based on any actual threats or plots” but has stemmed from the “rise in anti-government rhetoric.” This is largely connected to mask and vaccine mandates. The advisory states that, “through the remainder of 2021, racially- or ethnically-motivated violent extremists (RMVEs) and anti-government/anti-authority violent extremists will remain a national threat priority for the United States.” It warns that these extremists may seek to exploit the resurgence of COVID-19. Pandemic-related stressors have contributed to an increase in societal strains and tensions. In turn, this could lead to several plots by domestic violent extremists.

Houses of Worship and Commercial Gatherings Threat

Also included in Friday’s advisory, is a warning of the threat of RMVEs that sometimes target houses of worship and crowded commercial facilities or gatherings. As more institutions are beginning to reopen including schools, churches, synagogues, and mosques, there are several dates of religious significance. This includes the Jewish holidays Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur coming up in September. These significant dates could provide an increased target of opportunity for violence though there are currently no credible or imminent threats identified to these locations.

Online Threat

One other major warning of the advisory is for people to continue to be cautious of false narratives, conspiracy theories, and misinformation being spread online and through online communities. It states that:

“Ideologically motivated violent extremists fueled by personal grievances and extremist ideological beliefs continue to derive inspiration and obtain operational guidance through the consumption of information shared in certain online communities.”

Violent extremists may use messaging platforms or techniques to obscure operational indicators that provide specific warnings of a pending act of violence. Russian, Chinese, and Iranian governments, have all been linked to media outlets, aiming to “sow discord” and amplify conspiracy theories. These are largely concerning the origins of COVID-19 and the effectiveness of vaccines. This rhetoric has also led to amplifying calls for violence targeting persons of Asian descent.

Afghanistan Threat

While the report does not specifically mention the worsening situation in Afghanistan, it mentions acknowleges that:

“Al- Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula recently released its first English-language copy of Inspire magazine in over four years. This demonstrates that foreign terrorist organizations continue efforts to inspire U.S.-based individuals susceptible to violent extremist influences.”

It is a huge concern to both US government officials and their citizens that Al-Qaeda could rebuild in Afghanistan. Consequently, this may be a signifiacant threat under the Taliban rule. Unfortunately, this will lead to an increased threat of terror to the United State. Subsequently, this could become a major target of terrorist plots.

How the DHS is Responding

The DHS is taking various steps in response to these new threats. They are monitoring all online platforms to identify and evaluate calls for violence. This includes online activity associated with the spread of disinformation, conspiracy theories, and false narratives. The report moreover encourages the public to maintain awareness of the evolving threat environment and report suspicious activity.

The DHS is coordinating with state and local law enforcement and public safety partners. They aim to maintain situational awareness of potential violence in their jurisdictions and maintain open lines of communication with federal partners. Finally from a more broad standpoint, the DHS states that it will “remain committed to identifying and preventing terrorism and targeted violence while protecting the privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties of all persons.

Boko Haram insurgents (Photo Credit Ndtv: https://www.ndtv.com/world-news/nigerias-boko-haram-leader-dead-islamic-state-west-african-province-says-2457798)

Over the last few months the Nigerian armed forces have enjoyed a series of military victories against Boko Haram, who have also been plagued with infighting and defections. Notably the recent suicide of Boko Haram’s leader, Abubakar Shekau, marked a major blow to the Islamist terrorist group who, for the last two decades, have spread chaos and death, killing thousands across Nigeria.

Shekau’s suicide occurred not after a defeat to Nigerian government but at the hands of another terrorist organization, the Islamic States West Africa Province (ISWAP). Nevertheless, his death benefited the Nigerian government greatly, and was a severe blow for Boko Haram. Indeed, Boko Haram’s recent loss at the Battle of Sambisa Forest, emphasises the declining state of these terrorists. Not only was it a decisive defeat for Boko Haram, Sambisa was their former stronghold, but the fact that they lost to the ISWAP, another terrorist group with whom they had once been allied with marks a significant change in Boko Haram’s fortunes. This infighting illustrates the division and lack of unity between the Islamist terrorist groups in Africa. The Nigerian military has benefited greatly from this infighting and have pressed their advantage against the weakened and vulnerable Boko Haram.

Earlier this year, operation Hadin Kai saw Nigerian troops drive Boko Haram terrorists out of several of their territories in north-eastern Nigeria, including Borno state and Damboa. The Operation was commended for destroying several known terrorist camps in Borno before moving on to capture the resident rebels. Other detachments engaged the Domboa terrorists in intense combat and drove them into retreat. These decisive victories were both an enormous morale boost for the Nigerian military, and a PR Coup for the government, as previously their military had often suffered repeated defeats and heavy casualties of the course of their conflict with the Boko Haram. Now that the tide appears to be changing and Nigerian forces are winning battles in regions where once they had suffered ignoble defeats.

While the Nigerian military have been successful against Boko Haram before, Shekau’s death and the subsequent news that more than a thousand members of the organization have since surrendered to the Nigerian forces, signal a radical change in Boko Haram’s fortunes. Another key indicator is collapse of support for Boko Haram among their former allies and their own fighters. Since May, hundreds of Boko Haram fighters voluntarily surrendered in Cameroon. The surrender of these soldiers was likely driven by a loss of faith in their cause, rather than fearing a decisive military defeat.

Throughout history insurgencies have been notoriously difficult to defeat on a permanent basis. Guerrilla fighters and insurgents such as Boko Haram use hit-and-run tactics, striking without warning, before slipping away into the shadows to be sheltered by sympathisers. These tactics make it difficult for conventional troops to defeat insurrections in the long-term. Guerrilla groups also rely on spreading an ideal and romanticised image of their cause to gain supporters; narratives of martyrdom and dying heroically for the cause are key to inspire potential new recruits to take up the mantle and continue the fight. Thereby allowing these insurgent conflicts to last for many years. Such tactics have ensured the success of guerrilla insurgencies throughout history across the world.

The mass surrender by Boko Haram fighters indicates that one of the insurgent’s key weapons, the ability to inspire and recruit new members, is weakening. It has been thought that this may be due in part to Shekau’s suicide as the large number of defections started after his death. This suggests that he personally was a critical element holding the organization together as, without him, hundreds are no longer committed to Boko Haram.

Without the charismatic leader who inspired them, Boko Haram’s ideological grip on its members suddenly appears fragile. And time is against them. The Nigerian forces are “poised for a final routing” of the insurgency. Whilst the war is not over, this year marks a significant change of fortune for Boko Haram. They are now in a clearly vulnerable position to the Nigerian forces, who are pressing their advantage relentlessly, and continue to take decisive steps to finally defeat Boko Haram.

On October 7th, 2001, former president George W. Bush launched the war in Afghanistan, following the 9/11 attacks. 20 years later, current President Joe Biden says, “it’s time to end America’s longest war,” as he announced that the United States is pushing for a full withdrawal of troops by September 11, 2021. The 3,500 troops remaining in Afghanistan will be withdrawn, regardless of whether progress is made in intra-Afghan peace talks or the Taliban reduces its attacks on Afghan security forces and citizens. NATO troops in Afghanistan will also leave.

Leaders in Washington will continue to assist the Afghan security forces and do all that can be done to support the peace process. However, the Taliban has stated that it will not participate in “any conference” on the future of Afghanistan until all foreign troops leave.

There are very mixed responses to this announcement. This is likely due to the Taliban’s psychological and military momentum in the country. The Taliban is an Islamic fundamentalist group that ruled in Afghanistan from 1996-2001, following the U.S.-led invasion. Since then, it has waged an insurgency against the U.S.-backed government in Kabul. Many experts are concerned that the Taliban is stronger now than ever. They currently control over half of Afghanistan’s districts.

The first direct peace negotiations with the Afghan government began in 2020, signing an agreement with the United States. However, little progress has been made.

Former President Bush called the US troop withdrawal from Afghanistan a mistake and predicted that the consequences, especially for Afghan women and girls, will be “unbelievably bad.” Former Secretary of State, Hilary Clinton has also voiced her concerns about the Taliban regaining control if the US withdraws its troops. She has stated that:

“This is what we call a wicked problem. There are consequences both foreseen and unintended of staying and of leaving. The US government has to focus on two huge consequences: the resumption of activities by extremist groups and a subsequent outpouring of refugees from Afghanistan.”

Clinton furthermore highlighted that the potential collapse of the Afghan government and a possible takeover by the Taliban, could result in a new civil war. On the flip side, Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont does not think the troops should be there. Former President, Donald Trump, advocated for US troops to return home and subsequently criticized the US military interventions for being costly and ineffective.

When the war began in 2001, the public largely supported it. In early 2002, 93%, a record high, of Americans supported the war. As time went on and troops remained, majorities continued to hold these beliefs between 2004 and 2013. Then for the first time in 2014, an equal amount of people believed that it was a mistake. More and more people began believing that it was a mistake and the war made the US less safe. In 2021, 47% say U.S. military involvement was a mistake; 46% say it was not. From a political party standpoint, the recent polls show that 56% of Democrats and 29% of Republicans now say it was a mistake.

There is no military path to victory and peace talks are believed to be the best way to resolve the insurgency. Many U.S. security experts remain concerned that under the Taliban’s rule, Afghanistan would remain a safe haven for terrorists, who could launch attacks against the United States and its allies.

In its 2021 report, the United Nations team that monitors the Taliban has gathered significant data. This has demonstrated that the group still has strong ties with al-Qaeda. The Taliban continues to provide al-Qaeda with protection in exchange for resources and training. Between 200-500 al-Qaeda fighters are believed to be in Afghanistan, and its leaders are believed to be based in regions along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border.

Biden is optimistic that the withdrawal will be completed by the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. The current United States Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, said the Biden administration was “very focused on a deliberate, safe and orderly” withdrawal of troops, but that the US would continue to assist the Afghan government. “Even as our forces are pulling out of Afghanistan, we are not withdrawing – we are not disengaging.” Also adding that if US troops were attacked before leaving the country, “decisive action” would be taken.

Biden and those who support the drawdown made this decision based on the U.S. accomplishing its main goals in Afghanistan: finding the terrorists who orchestrated the 9/11 attacks, killing Osama bin Laden and trying to limit the country’s base of operations for terrorists. Nation-building was not part of the original strategy, and this is a war that has dragged on for too long, costing the U.S. far too many lives and money.

Background

On July 9th, South Sudan celebrated ten years of independence, remembering how its people overwhelmingly voted for independence from Sudan in 2011. But another entity, the United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS), is also marking ten years of existence this year. Initially meant to consolidate peace and development in the world’s youngest country, UNMISS has grown into the largest UN peacekeeping operation in the world, currently deploying 19,233 personnel. With a budget of over $1.2 billion for the 2020-2021 fiscal year, it is also the second most expensive ongoing UN mission. This is after the mission in Mali. This article hopes to analyze this monumental mission that has shaped a country.

Early UN attempts at state-building were violently reoriented by a civil war between President Salva Kiir and opposition leader Riek Machar and by broader communal violence between (and within) their respective Dinka and Nuer ethnic groups. Though a 2018 peace agreement facilitated the tenuous formation of a unity government in 2020, a recent UN report found that violence has only gotten more brutal, unaccountable, and decentralized since the end of the country’s civil war. The Government of South Sudan (GoSS) has failed to implement major security and accountability measures from the peace agreement. Consequently, its security forces are frequently accused of obstructing peacekeepers and violating civilians’ human rights. With the UNSC recently renewing UNMISS’ mandate until 2022 and establishing a three-year “strategic vision” for the country, practitioners are tasked with interpreting mission effectiveness within the four key pillars of the mandate.

The UN Mandate

Keeping in mind the centrality of the mandate to any UN mission, this article uses UNMISS’ updated mandate as a point of departure for evaluating mission effectiveness. It will also keep the 2018 peace deal as an additional guideline. The terms of the mandate reaffirmed in 2021 are essentially the same as those in Resolution 2155 (2014), which was updated when the nascent country fell into civil war. With some important clarification in the language in the 2021 resolution, the four pillars are broad: protection of civilians, monitoring of human rights abuses, facilitation of humanitarian aid delivery, and supporting the active peace agreement.

Sadly, these four pillars look nothing like the original mandate from 2011. This is because UNMISS has had to drastically scale its ambitions back from consolidating the state to alleviating and containing a multi-dimensional crisis. Using the mandate itself to measure effectiveness is essential. In part, it reflects the wishes of concerned multilateral actors and frames what the mission is actually allowed and expected to do. This article distills the goals of the mandate into two broad, dynamic criteria for evaluating UNMISS: providing protection and facilitating aid to civilians and promoting institutional stability and security. These have been constant, salient challenges facing UNMISS, and they encompass much of what the mission is there to achieve.

Providing protection and facilitating aid to civilians

Though UNMISS can only exist with the consent of the GoSS, one might forget considering how often peacekeepers are blocked or even attacked by government forces. The UNSC acknowledged this in 2014 and again in Resolution 2567 (2021), when it “[condemned] the continued obstruction of UNMISS by the GoSS and opposition groups, including restrictions on freedom of movement, assault of UNMISS personnel, and constraints on mission operations.” Government intransigence amid vast civilian suffering presents UN personnel with difficult decisions and frequent occasions of paralysis in the face of violence against civilians. Since it cannot achieve protection of civilians (PoC) in every case, UNMISS has also been tasked with reporting on government privations, hoping for long-term accountability through documentation and human rights pressure.

Though UN missions are frequently criticized for the lives they fail to save, a critical analysis must try to understand what would have happened had peacekeepers not been there. As of 2020, there were almost 200,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) inside UN-administered PoC sites. UNMISS’ recent focus has thus been protecting civilians and administering aid and basic services in and around these sites. This establishment of veritable peace corridors is reminiscent of early visions of peacekeeping, but even through this lens, UNMISS can only be viewed as semi-successful. This is because it has frequently been unable to protect civilians and aid workers within its own PoC sites. Subsequently, it has had little success expanding the domain of its PoC sites outwards. There remain 1.5 million IDPs outside of PoC sites. Ultimately, violence against civilians and aid workers has continued and even worsened since the end of the civil war.

Similar things can be said for humanitarian aid. The UN has estimated that 8.3 million South Sudanese are currently in need of humanitarian assistance, an increase of 800,000 from 2020. Both sides were known to intentionally starve communities during the civil war, and the GoSS continues to block access to peacekeepers and aid workers seemingly at will. Though a great deal of aid has moved through roads restored and protected by UNMISS, GoSS corruption and violence and the frequent pilfering of humanitarian goods have deterred major international donors in recent years. UNMISS should leverage these once-eager financiers against GoSS intransigence, putting economic pressure on a government reliant on international support.

Promoting institutional stability and security

In terms of building a stable and responsive state in South Sudan, the 2018 Revitalized Agreement offers valuable metrics, such as refugee resettlement, rebuilding of physical infrastructure, and finalization of a permanent constitution. Unfortunately, any traction on these issues is largely out of the hands of UNMISS. This is because African regional organizations have led the way in mediation and implementation. Relations with the GoSS have soured ever since the 2014 mandate said UNMISS would protect civilians “irrespective of the source of…violence,” tacitly pitting it against government troops.

But the mission is not completely ineffective on the political front. At a community-level, UNMISS-facilitated dialogues have deescalated violence in numerous areas recently. There is significant potential to partner with communities instead of the GoSS, but UNMISS has yet to hire a sufficient number of community liaisons to foster engagement. Subsequently, its patrols have been notably hesitant to engage on foot in communities. These are tangible policies UNMISS must correct if it is to overcome the challenges posed by the government. UNMISS should institutionalize and expand these often-successful dialogues for reconciliation and deradicalization in local South Sudanese communities.

Conclusion

It is certainly better for hundreds of thousands of South Sudanese that UNMISS was deployed, but with its resources, the mission could do far more to push the country in a constructive direction towards peace. From a strictly peacekeeping lens, UNMISS receives a somewhat passing grade for establishing areas of relative protection. But with the post-Cold War pairing of peacekeeping and peacebuilding, UNMISS has fallen flat. Frequently marginalized from the peace process, it has largely abdicated its role in shaping post-war South Sudan.

Most South Sudanese remain susceptible to factional violence and dire humanitarian need, and little has been done to grow state capacity or even state interest in helping them. As much good as UNMISS has done in specific areas, it can only be national stability that helps those millions of South Sudanese still living on the precipice. And now that UNMISS has begun transitioning its PoC sites into GoSS-controlled IDP camps, it is unclear what major tools are left for this mission to fulfill its mandate.

Overall, UNMISS has a great deal of experience and success to pull from but has not been bold enough in tackling one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises. The UN must either recommit to the political process in South Sudan or accept that it is merely being used to protect a civilian population ignored by the government. It should also expand and standardize conflict resolution initiatives of the kind frequently highlighted in its own reports. Much of the violence in South Sudan stems from specific, community-level disputes. Engaging with at-risk communities and investing in specialized civilian personnel would go a long way towards saving lives in South Sudan.

Introduction

United Nations peacekeeping operations are meant to help countries down the complex path of peace and reconciliation. Such peacekeeping missions are mandated by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). A smaller subset of peacekeeping missions, stabilization operations, are not regulated by the UN Charter, but make-up three of the four largest ongoing peace operations. Their legitimacy rests between Chapter VI (peaceful settlement of disputes) and Chapter VII (use of force to restore peace), constituting the so-called “Chapter VI and a half.” These operations are a joint instrument of the Security Council (the highest political authority) and the Secretary-General, the highest administrative and functional authority of the organization.

Peacekeeping interventions are based on some strategic points, including legitimacy, burden sharing, and the possibility of deploying and integrating police forces and civilian personnel. The work that the UN conducts during peace operations is based on three fundamental principles, namely consent to intervention by countries in conflict, impartiality, and non-use of force (unless in self-defense or in defense of the mandate).

Thousands of “Blue Helmets,” the military body belonging to member states and “loaned” to UN missions, have over time morphed from mere observers limited to logistical and technical support to being assigned sensitive functions. They now operate more complex programs including political mediation, de-mining, public affairs and communication, protection and promotion of civil rights, and reintegration of combatants into society. The missions have thus become multidimensional and integrated.

Instability is not just a military fact, with a truce to guard or a cease-fire line to patrol, but has many causes. Stabilization operations thus include ever greater responsibilities, including the democratization of local institutions, economic and social development, environmental and natural resource protection, and the retraining of military forces, police, and prison services, according to modern, democratic criteria.

Africa

An example of these new and expanded functions are assistance and support missions, which are deployed in countries that have seen the total collapse (or almost total degradation) of state structures, countries such as Libya, Sierra Leone, Mali, Central Africa, and South Sudan. UN functions are also diversified and no longer restrained to patrolling truce lines. They have been involved in such diverse efforts as decolonization in Namibia, independence in Eritrea, protection of populations in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the transition to democratic regimes after years of civil war in Angola, Mozambique, Central America, or West Africa. All these missions see not only the change in the profiles and structures of the missions but also their composition.

In West Africa, there are two very different missions, MINURSO and MINUSMA. The first aims to ensure, sooner or later, the holding of a regular referendum in the territories of Western Sahara, still disputed between Algeria, Morocco, and the local population. The mission has been active since 1991 and has 485 units, of which 245 are military.

MINUSMA, in Mali, started in 2013 shortly after the French military operation Serval, which halted the advance of Tuareg and other armed groups towards Bamako. Despite the collaboration with Operation Barkhane (formerly Serval) and the G5 of the Sahel, the area is still deeply unstable. MINUSMA’s annual budget exceeds one billion dollars and over 15,000 military personnel are deployed. The states that support the mission militarily are interested in containing the Malian crisis (Burkina Faso, Chad, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal).

As for Central Africa, MINUSCA is the stabilization mission of the Central African Republic. It was born in 2014, following the outbreak of civil war. Despite numerous peace agreements signed between parties, skirmishes and structural violence remain. The mission has an almost exclusively “regional” character since the troops present are Rwandan, Egyptian, Zambian, Cameroonian, and Senegalese. MONUSCO, on the other hand, is an operation that started in 2010 and aims to stabilize the Democratic Republic of Congo, devastated first by spillover from the Rwandan genocide of 1994 and then by its own wars from 1998 to 2003, which left over 5 million dead.

Additionally, three peacekeeping missions are active in the Horn of Africa, two in Sudan and one in South Sudan. The last one, UNMISS, was born in 2011 in South Sudan. After gaining independence, the country fell into a bloody civil war, dictated by patriotism and exploitation of ethnic tension, which have been intensifying since December 2013.

Analysis

Over the years, this United Nations instrument has been criticized extensively but has also received some positive feedback. Too often, in the initiatives of the powers that act in the name of the so-called international community, in which Africa, politically speaking, seems to be considered more an object than a real subject, the goal of “security” prevails. Very often, the issues of jihadism and human mobility towards Europe are considered separately from other issues plaguing African governments. There is a need for a repositioning of international diplomacy that considers the constant and progressive modification of the African geopolitical chessboard in the age of globalization.

The colonial and postcolonial models, to the test of facts, no longer represent a paradigm of reference in Africa for the control of aid institutions or even investments. The traditional partners of African countries (the former colonial powers) must now compete with the low index of “conditionality” strategies of emerging powers such as Brazil, China, India, Turkey, and Russia itself, which is reappearing in Africa after the withdrawal imposed, about thirty years ago, by the collapse of the Soviet Union.

It is precisely within these parameters that the United Nations, as an organism of peoples, is called to play an indispensable role. It is worth recalling what happened in the early 1960s with the wave of African independence movements. At that time, the UN, established as an organization after World War II with the aim of preventing future conflicts by replacing the ineffective League of Nations, played a politically relevant role.

In particular, the recognition of the principle of self-determination of peoples, sanctioned by the United Nations Charter, received a warm response. International law also outlawed war, in particular, due to Articles 2 & 4 of the Charter, declaring that member states must renounce war and resolve their conflicts.

To weigh negatively on these missions are a series of factors found in many investigations. The first of these factors is the lack of discipline among Blue Helmets and the fact that the contingents are sometimes composed of soldiers from countries where training standards are not adequate for modern crises in Africa. There have also been pervasive issues of sexual violence against women and minors.

Regardless, the United Nations has taken a central and irreplaceable role in the building of congenial international relations in the modern era. In the case of the African continent, the UN provides international legitimacy and an irreplaceable and indispensable forum for negotiation at global level on the issues of development, peace, and security.

Over the last weekend, the Taliban continued its country-wide offensive, successfully capturing several Afghan provincial capitals. While the U.S. continues to pin its hopes on a Taliban-Afghan government peace deal to halt the country’s relentless violence, the reality on the ground tells a different story. The Taliban’s offensive casts serious doubt on its supposed desire to reach a peaceful resolution. The U.N. special envoy for Afghanistan, Deborah Lyons, has questioned the Taliban’s commitment to a political settlement.

The statements of the Taliban’s Doha-based political office regarding their willingness to negotiate are no more than smoke and mirrors, maintaining a glimpse of hope for the West for a peaceful resolution while at the same time continuing the offensive. It represents a conceptual failure of the West in understanding the organizational nature of the Taliban. The Taliban, with all of its branches, is a terrorist organization, or more precisely, a hybrid terrorist organization.

Definitions

Terrorism is the deliberate use of, or threat to use, violence against civilians or against civilian targets, in order to attain political ends. The terrorist has political goals, whether nationalistic, separatist, socioeconomic, or religious. The Taliban’s end goal, for example, is to establish an Islamic caliphate in Afghanistan. Terrorism is differentiated from criminal violence by its deliberate use of violence against civilians for political ends.

A hybrid terrorist organization is one that stands on multiple legs. First, it has a military or paramilitary leg that engages in terrorist acts. Second, it has a political leg that allows the organization to operate and win in both the “illegitimate” arena of terrorism and the “legitimate” arena of the media. Third, it acts as an alternative provider of welfare services through seemingly innocent organizations serving a potential or actual constituency. Among jihadist organizations such as the Taliban, this activity is known as da’wa and subsumes a combination of religious services, educational services, ideological indoctrination, and welfare services.

The Taliban as a Hybrid Terrorist Organization

The Taliban’s operations today are divided between its three legs: military, political, and social welfare-da’wa.

Its military forces are advancing on all fronts, seizing provincial capitals, and increasingly utilizing terror tactics against civilians and governmental installations. In recent weeks, the Taliban kidnapped and executed a popular Kandahari comedian Nazar Mohammad, apparently because he ridiculed Taliban leaders. The Taliban tried to assassinate the acting defense minister Bismillah Khan Mohammadi in a bombing attack, leaving dozens dead but failing to kill the minister. The Taliban shot and killed the director of Afghanistan’s government media center, Dawa Khan Menapal, after ambushing him in Kabul. In its overall strategy, the Taliban has been conducting summary executions, beating up women, shutting down schools, and blowing up clinics and infrastructure.

Its political office presents a different face. From its seat in Doha, Qatar, the Taliban’s political office maintains its commitment to negotiation and a peaceful resolution of the conflict. The Taliban has dispatched delegations to Russia, China, and Iran in hopes of gaining international legitimacy. Finally, the Taliban has also emphasized its willingness to grant rights to women.

As part of its da’wa efforts, the Taliban has created a network of Islamic religious schools, called madrasas, all across the country. These schools attract many poor families because the Taliban cover all expenses and provide food and clothing for the children. On some occasions, the Taliban has encouraged families to send their children to their schools by offering families cash. These schools are used as recruitment and training sites for the Taliban.

Conclusions

Despite what it may say, the Taliban has not changed and holds the same views as it did before. The only difference is that it has become more sophisticated in its use of technology and is better integrated within the jihadi universe. In order to successfully confront the Taliban, the world must first conceptually understand the nature of the organization. Second, it must designate all of the Taliban’s operational legs as part of the same hybrid terrorist organization. Finally, this designation will enable the world to use counterterrorist strategies to better confront all of the Taliban’s legs.