For over 1,000 days now, Yemen has been devastated by horrific violence and a brutal civil war.[1] In 2014, the Houthis, a group of Zaidi Shi’a rebels who subscribe to the principles of pan-Islamism,[2] advanced into the Yemeni capital of Sana’a. By January 2015, the rebels had gained control of the presidential palace and successfully pushed the Yemeni government from power.

A student at the Aal Okab school stands in the ruins of one of his former classrooms. He and his fellow pupils now attend lesson in UNICEF tents nearby.

President Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi was eventually forced to resign, parliament was dissolved and a Houthi ruling council was established in its place.[3] In March 2015, the Saudi-led military coalition targeted the Houthis and began bombing the rebels in an effort to dislodge them from Sana’a.[4] While the Saudi coalition was able to aid Hadi and various local forces in regaining southern governorates of Yemen, the Houthis continue to control much of the north- including strategic parts of the country such as Sana’a.[5] On December 4, 2017, Ali Abdullah Saleh, the former president of Yemen who had stepped down during the Arab Spring in 2011, was killed by the Iranian backed Houthis. Driven by the desire to regain power, Saleh and his loyalists formally allied with the Houthis in 2015. However, he broke ties with the rebels in December 2017 and days after expressing his support for Riyadh, the Houthis killed him.

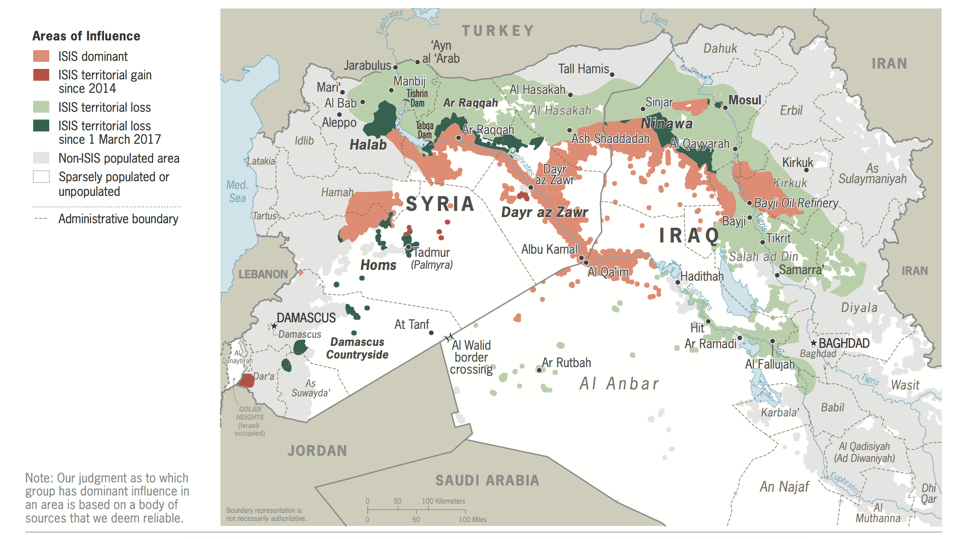

In Yemen, alliances seem to be constantly shifting and the political situation appears to be an endless quagmire. The unrest and dynamic conflict has enabled the Yemen based group, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), to greatly expand its territorial control and there are ISIS training camps in al Bayda governorate.[6] While AQAP remains a much greater threat than ISIS in Yemen, it is clear that the war torn country has become a breeding ground for terrorism. While a thorough analysis of the current political situation in Yemen is beyond the scope of this discussion, this piece will seek to examine the relationship between poverty and terrorism in Yemen. I will argue that while poverty is not the only underlying cause for terrorist activity in Yemen, it frequently serves as a mobilizing factor that aids in AQAP’s recruitment efforts.

Her bruised eyes still swollen shut, Buthaina Muhammad Mansour, believed to be four or five, doesn’t yet know that her parents, five siblings and uncle were killed when an air strike flattened their home in Yemen’s capital. Despite a concussion and skull fractures, doctors think Buthaina will pull through – her family’s sole survivor of the Aug 25 attack, on an apartment building, that residents blame on a Saudi-led coalition fighting in Yemen since 2015. The alliance said in a statement it would investigate the air strike, which killed at least 12 civilians.

The civil war in Yemen has produced the world’s worst humanitarian crisis as well as the world’s worst cholera outbreak. More than ten thousand innocent civilians have been killed,[7] over fourteen million people are without access to medical care and millions have been internally displaced by the conflict. The Saudi coalition has imposed a de facto blockade, which has significantly worsened the crisis and now roughly seven million people are at risk of famine.[8] The ongoing violence and extreme poverty in Yemen have left families extremely vulnerable. In the April 2016 United Nations annual report on children and armed conflict, the UN Secretary-General reported that…“in Yemen, a particularly worrisome escalation of conflict has been seen. The United Nations verified a fivefold increase in the number of children recruited in 2015 compared with the previous year.”[9]

Yemen is a state on the brink of collapse and this has produced an enabling environment in which extremists are much more successful at mobilizing support for their violent causes. One way terrorists have been able to exploit the extreme poverty of Yemen and gain new recruits is through social service provisions. AQAP has appeared in images and videos on Twitter, showing the group’s fighters paving roads in the Hadramout province and assisting local hospitals.[10] Elisabeth Kendall, a Yemen scholar at Oxford University, tells Reuters, “In one video posted on Feb. 28, 2016, AQAP members deliver free medical supplies and equipment to the kidney dialysis and cancer wings of a local hospital.”

In another video, an AQAP militant states, “These are some medicines from your brothers, the Guardians of Sharia, to al-Jamii hospital which was going to be closed … because of no money.”[11] The deputy prime minister of Yemen, Abdel-Karim al-Arhabi, is well aware of the relationship between violent extremism and poverty, especially when it comes to young boys who are often recruited as foot soldiers. Abdel-Karim al-Arhabi states, “Most young people have no prospects in life. Those fanatics offer them the illusion that they can take power and implement authentic Islam – and if they get killed they go to paradise. It’s a win-win situation for them.”[12]

Yemen has been in the grip of civil war since March 2015, when Houthi rebels drove out the government and took over the capital, Sana’a. The crisis quickly escalated, allowing al Qaeda and ISIS — enemies of the Houthis — to grow stronger amid the chaos.

It is clear that young men faced with high levels of poverty and little to no employment prospects are often lured to organizations like AQAP. AQAP not only provides social services but also the promise of financial rewards and compensation.[13] The links between poverty, unemployment and young Yemeni men joining al-Qaeda and its affiliates are not new. Salim Ahmed Hamdan, the first Guantanamo detainee to stand trial before the military commissions and a Yemeni citizen, worked as a driver for Osama bin Laden. The Sana’a based mosque where Hamdan was recruited was described as a “gathering place for the dispossessed,” and thus “exerted an especially strong pull on the country’s poor.”[14] Hamdan claimed to have chosen to work for al-Qaeda in Afghanistan because, “working as a driver and mechanic in bin Laden’s motor pool paid better than driving a dabab (minibus) in Sana.”[15]

In this discussion, it is vital to note that many researchers have claimed that the terrorism-poverty thesis is flawed. However, poverty’s role in undermining state capacity has often been overlooked and scholars have often failed to make distinctions between terrorist elites and impoverished communities. Karin von Hippel explains, “Although the leaders of terrorist organizations seem to come from both indigent and bourgeoisie backgrounds, this is not true of their humble servants. Strangely, most researchers recognize that poverty may be a factor among lower ranks but do not include the foot soldiers in their research when aggregating data”.[16]

We cannot dismiss the fact that elites often use the grievance of poverty as a recruitment mechanism and extremists continuously exploit ungoverned or disputed territory. Corinne Graff of The Brookings Institution contends, “There is little evidence to suggest that poverty does not affect the incidence of terrorist attacks. The body of scholarly research thus far has failed to establish this, let alone explain how to measure terrorism. Hence the quantitative data and ensuing data disputing such a relationship remain a poor guide for policy. More convincing is the mounting evidence confirming that poor weak states are vulnerable to violent extremists.”

Abdellatif Allami walks with his three-year-old daughter Sara in the Harat Al-Masna’a slum in Sana’a, home to the families of former factory workers. They used to receive a basic pension of around $120 a month, but the payments stopped seven months ago, and the families now rely on donations to survive.

We cannot simply overlook the fact that “an estimated 17 million Yemenis (about 60 percent of the total population) are estimated food insecure and a further 7 million severely food insecure…malnutrition has increased by 57 percent since 2015 and now affects close to 3.3 million people, 462,000 of which are children under five.”[17] If the state truly does collapse, Yemen will not only become a terrorism hotbed for Sunni jihadists but also for Iran backed Shia militant groups.

Sources:

[1] Faisal Edroos and Ahmad Algohbary, “1,000 days of war in Yemen ‘land of blood and bombs'”, Al Jazeera, December 20, 2017.

[2]“Q&A: What do the Houthis want?”, Al Jazeera, October 2, 2014.

[3]“Yemen: Houthi, Saleh council formation criticised by UN”, Al Jazeera, July 29, 2016.

[4] “Saudi Arabia launches air strikes in Yemen”, BBC News, March 26, 2015

[5] “Yemen Control Map & Report – January 2018”, Political Geography Now, January 7, 2018.

[6] DoD News, Defense Media Activity, “U.S. Forces Conduct Strike Against ISIS Training Camps in Yemen”, October 16, 2017, U.S. Department of Defense.

[7] Nicolas Niarchos, “How the U.S. Is Making the War in Yemen Worse”, The New Yorker, January 22, 2018.

[8] Rick Gladstone, “U.S. Agency Foresees Severe Famine in Yemen Under Saudi Blockade”, The New York Times, November. 21, 2017.

[9] United Nations General Assembly Security Council. “Children and Armed Conflict, Report of the Secretary General” A/70/836–S/2016/360.

[10] Yara Bayoumy, Noah Browning and Mohammed Ghobari.“How Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen has made al Qaeda stronger – and richer”, Reuters Investigates, April 8, 2016.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ian Black, “Yemen terrorism: Soft approach to jihadists starts to backfire as poverty fuels extremism” The Guardian, July 29, 2008.

[13] Christopher Swift, “Arc of Convergence: AQAP, Ansar al-Shari’s and the Struggle for Yemen”, CTC Sentinel 5, no. 6 (2012).

[14] Susan E. Rice, Corinne Graff, and Carlos Pascual, Confronting Poverty: Weak States and U.S. National Security, (Washington, DC, Brookings Institution Press, 2010), 69.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Karin von Hippel, “The Role of Poverty in Radicalization and Terrorism” Debating Terrorism and Counterterrorism (Thousand Oaks: Congressional Quarterly Press, 2014), 61.

[17] “The World Bank in Yemen”, The World Bank, April 1, 2017.

[print-me]