Passers-by flee the scene of the attack, which saw a truck rammed into a shopping centre in Stockholm, PA: Press Images

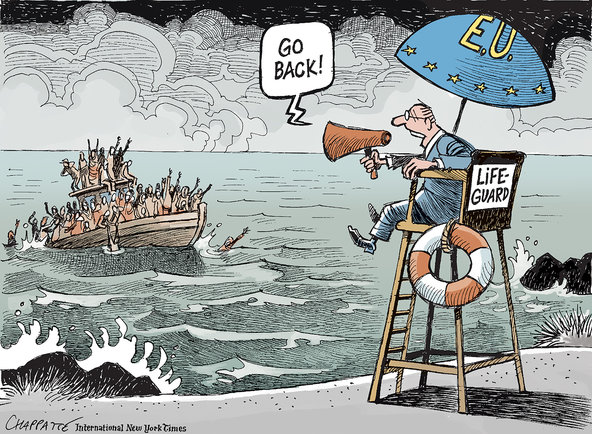

Europe has been on high alert for terror attacks in major metropolis around the region. Complicating the matter are questions over immigration, asylum, religious freedom, and how countries can absorb and integrate masses of refugees.

Scandinavia, with its welfare-state propensity and open-minded lifestyle, is bearing the brunt of these issues. There is no contemporary precedent for how to peacefully integrate vast numbers of diverse asylum seekers into the relatively small, homogeneous population of Scandinavia. This makes the outcome of the current situation questionable.

One sure consequence is the rise of right-wing ultra-nationalism. Right-Wing ultra-nationalism secures its power by stoking fear and conflict over asylum seekers and immigrants. Finding a framework and process for peaceful integration is necessary to avoid extremist ideology exposure. Scandinavian governments will be tested as they balance privacy and security, maintain religious freedom, and create equitable, transparent processes.

Scandinavians value their privacy and individual freedoms, yet have been forced by terrorist attacks to consider the trade-offs they must make for better security.

Questions dominate the Scandinavian discourse such as whether a government should attempt to mitigate attacks by raising physical barriers in city centers, or by focusing on defeating extremist ideologies, or whether immigrants and citizens should be allowed their right to privacy.

Homogeneous populations like those in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Denmark have been attacked by extremists as recently as 2017. In April a truck attack in Stockholm killed five and injured more. In August two people were killed and 10 more wounded in a stabbing in Turku, Finland. Both perpetrators were asylum seekers.

Concurrently, the number of radical extremists on Sweden’s intelligence radar has risen from 200 to 2,000.

The number of asylum seekers in Europe peaked in 2015 but remained above 550,000 in 2017. In Sweden and Finland alone, 200,000 asylum seekers have been admitted since 2015. Concurrently, the number of radical extremists on Sweden’s intelligence radar has risen from 200 to 2,000.

Most Nordic countries have programs which aim to build resilience and identify at-risk populations. Finland has programs wherein troubled youth are admitted and subsequently, social workers share information they gather with local police. Many similar programs fan out across the region, but they tend to be voluntary and underfunded. Many Scandinavian citizens are concerned about privacy and thus support these programs’ voluntary nature.

There are cultural and religious tensions between Muslim immigrants and the Scandinavian people, the latter of whom tend to exhibit low levels of religious adherence. And then there are religious divisions within Islam which leads to tension. Many of the asylum seekers are Shia.

The majority of Muslims resided in Scandinavia previously are Sunni. Established, Finnish Sunnis have perpetrated hostilities against the newly arriving Shia. Not only is Scandinavia struggling to cope with how to integrate a foreign-born population, but it must also contend with ancient animosities between foreign-born populations. Given the high levels of atheism in much of Scandinavia, the religious divide is slippery and has some questioning whether it is the religious leaders’ responsibility to quell animosity or the government’s job to vet asylum seekers.

Local citizens, asylum seekers, and civil society have hotly criticized the integration process.

In particular, in 2016, Denmark was criticized for its jewelry law which required immigrants to forfeit assets over £1,120, irrespective of family heirlooms, wedding rings, and other sentimental pieces. Some Danes believed the policy was equitable because Danish citizens seeking government assistance could not hold general assets of greater value. However, asylum seekers and NGO representatives believe it is punitive.

The rationale was that immigrants should not be allowed to keep savings and other assets and still expect the Danish government to pay for housing and food when Danish citizens are not allowed the same opportunity. Is a country like Denmark, known for being open-minded and tolerant, still both of these when assets are being confiscated?

The public needs a better understanding of the motivation behind these laws to avoid the populist rise and extremist response across Scandinavia.

As it turns out, low-income Danes, immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers are all treated equally under the law. In addition to free housing and food, they are all provided free education. The public needs a better understanding of the motivation behind these laws to avoid the populist rise and extremist response across Scandinavia. Scandinavians worry what will become of their welfare system and wonder how far they can stretch their resources. Asylum seekers see these measures as discriminatory.

Neither Scandinavian nor international media, nor governments are doing enough to counteract both sides’ fears. There has been a consequent rise in extremism by nationalist groups, evidenced by Norway’s government which touts the primacy of Norwegian values, and by the fascist roots of the Swedish Democrats party which has been gaining momentum.

If these countries wish to maintain their open-minded reputations they must review the foundational ideologies on all sides and address the challenges of successful integration.

This should include finding a balance between privacy and security, as well as seeking greater empathy and transparency from all parties. “Xenophobia, racism, and welfare chauvinism have gone mainstream in Scandinavia,” says Mette Wiggen, a prominent analyst of the radical-right. Unfortunately, there is no playbook for how to keep this from spiraling out of control.

One thing is certain: if concessions are made on all sides, and there is tolerance, care, and dialogue, Scandinavia can set a precedent for how to integrate asylum-seekers as they have for governance and quality of life for years.