Filipino and American forces shaking hands in September 2017. Image Credit: Cpl. Robert Sweet, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command.

The recent tension between the Philippines’ security forces and Islamic separatists has exposed the cultural, economic, and military inefficiencies of the central government in countering terrorism. Strengthening cooperation with the United States will help the government tackle these issues more effectively, helping them solve some of the coordination and collective action problems which currently plague their operations. By briefly covering the history of the conflict, stating who the major extremist groups are, and examining how they act, this article shall propose recommendations that can promote further cooperation to counter extremism, encourage more cultural and religious cohesion in civil society, and help break up the revenue-generating activities of terrorist groups in the Philippines.

The church bombing in Jolo on January 27th 2019, which killed twenty people, highlights the recent flare-up in tensions between Catholics and jihadist groups in the Mindanao region. This attack came just days after a referendum of autonomy was held in the area where the majority of citizens voted to approve the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region. The referendum was part of a deal between the government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) – an organisation that has been fighting for independence for decades.

The country has been a victim of these attacks before, all claimed by ISIL and its affiliates. On August 28th, 2018, an improvised explosive device (IED) tore through a festival in Isulan in the same region as the church bombings. On July 31, 2018, a bomb exploded in a van at a security checkpoint on the southern island of Basilan, killing ten and wounding eight. In 2017 a group of pro-Islamic State (IS) jihadists captured and held part of the city of Marawi in the province of Lanao del Sur.

Historically, the security and police forces of the Philippines have failed to deal with extremist groups active in the South Philippines such as Abu Sayyaf/ISIL, the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters, and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front. The source of tension dates back to Islamist militancy in the 1970s, while groups such as ISIL relative newcomers to the region. IS, however, has yet to acknowledge the Philippines as an official wilayat, or franchise.

Despite this, dozens of groups in the Philippines claim allegiance to IS. They have even aided the Maute group – an ISIL affiliate – in seizing strategic parts of the city of Marawi on the 23rd May 2017 in a standoff with government security forces- causing 1,100 fighter and civilian deaths and the displacement of 400,000 people. The conflict subsided with the government’s evacuation of residents in the city and the subsequent bombing campaign. The execution of the two main jihadist leaders in the Philippines, Isnilon Hapilon and Omar Maute, ended the conflict but also created a hotbed for extremist activities that further destabilized the region. The Filipino military alone is ill-equipped to deal with these types of insurgent groups, facing a lack of capacity, poor coordination, and geographic obstacles in its struggle to fight extremism. Although one hundred US military advisers were on the field, in addition to US and Australian intelligence support, their combined strength was not enough to stop a credible, potent jihadist threat.

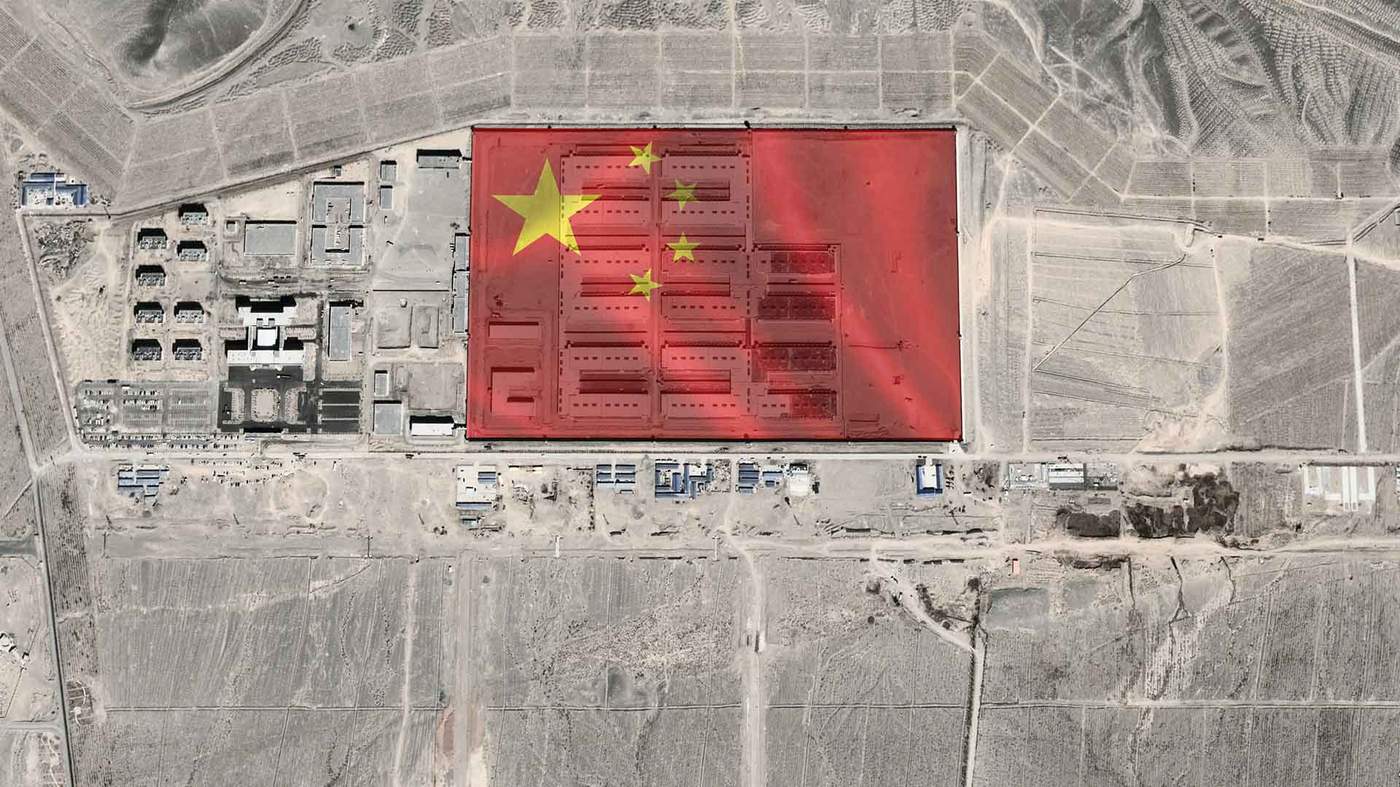

Map displaying the location of Marawi. Image Credit: BBC.

In 2015, the US ended the campaign of Operation Enduring Freedom – Philippines, which was formerly the largest counter-terrorism operation in Southeast Asia. Research shows that the presence of US Special Operations Forces (SOF) to train and equip, advise and assist, and contribute to civil/military information operations helped reduce the level of support for terror groups. The presence of US SOFs also improved the tactical and operational efficiency of the Philippines Security Forces. With an average presence of 600 SOF present in the Philippines between 2001-2014, this number has now plummeted by more than half. The latest news reported the US would increase the number of SOFs to 261 in joint military operations with Filipino security forces. In 2019, uncertainty surrounding the American presence in the Middle East also holds implications for the American presence in the Philippines, potentially threatening their battle against internal extremist forces. With planned withdrawals from Syria and Afghanistan and an overall laissez-faire approach to US military presence around the world, it is unclear whether the US will maintain or increase cooperation with the Philippines in areas such as counter-terrorism, maritime security, and humanitarian aid.

US presence in the region makes a significant difference. Recommendations to improve counter-terrorism strategies include targeted US involvement in maritime security to prevent IS-affiliated groups such as Abu Sayyaf from carrying out kidnap-for-ransom operations on ships going through the South China Sea. As of 2016, the group has raised around $7 million from kidnapping operations, using this money to finance further extremist activities. Maritime security can prevent these groups from conducting successful kidnappings and have a positive impact by helping the Philippines combat other internal challenges. For this cooperative relationship to operate well, the government must also form stronger partnerships with Malaysia and Indonesia to encourage intelligence sharing and patrolling of sea lanes, which they have already carried out through trilateral patrols. Moreover, strategic partnerships with Japan, South Korea, and Australia can help only with the US acting as a facilitator and leader on this front. Without this guidance, counter-terrorism strategies are much less effective. Careful communication and constructive cooperation might even help in convincing the US to re-establish its Joint Operations Task Force – Philippines to contain a potential rising terror threat.

For the IS, the Siege of Marawi was a propaganda victory which enabled them to extrapolate a local conflict into a larger Muslim-Christian sectarian war. Being able to hold the largest city in the southern region of the Philippines gave the group legitimacy in jihadist circles and enabled the recruitment of more foreign fighters from Indonesia and Malaysia. As a result, this development has lead to fears that the Philippines will become a hub for terrorists fleeing places where ISIL have lost ground, such as Iraq and Syria.

To counter this threat, the Filipino government must not only use military means, but religious and cultural ones as well. Research by DAI published in August 2018 showed how marginalization and discrimination were stronger predictors of violent extremism than poverty, social conflict, or corruption. The government of the Philippines should therefore strengthen its cooperation with civil society groups on the ground and encourage the development of more cohesive communities. The government has already put in place a policy that would include Muslims in the military. This can lead to more support from the local community, especially in the Mindanao region, and help create room for dialogue. Further policies, such as encouraging millenials with influential social media presence to spread the message of peace or strengthening the government’s deradicalisation programme, can go a long way to help bridge the differences within civil society and marginalized religious communities.

Dialogue can also be a constructive tool at the international level. A balanced tone must be struck, and Duterte must abandon the use of nationalist and inflammatory rhetoric against the presence of US troops. Effective diplomacy can encourage the American government to strengthen their relationship with the Philippines through continued humanitarian aid, technical military assistance, and engagement with local government, civil society, and ASEAN through Congressional delegations and non-governmental organisations. Efforts such as the adoption of the Langkawi Declaration on the Global Movements of Moderates in 2015, pushing for a more moderate political environment within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), are steps in the right direction.

The Philippines must also follow up on lessons learned from training with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the Anti-Money Laundering Council to closely monitor the economic maneuvers of domestic extremist groups. It is already a member of the Asia Pacific Group (APG) on Money Laundering and is no longer subject to its monitoring process. However, the IS have been funding smaller extremist groups, including the Maute Group, which now engages in looting, kidnapping, and the illegal drug trade to finance their activities. As Duterte’s disastrous war on drugs has shown, it is wise to use means other than military force to combat illegal activities. To combat this problem, the US should not only strengthen trade cooperation with the Philippines, but also play an active role in setting up stable financial architecture in the region to counteract more illicit money-laundering operations, such as those by North Korea.

In order to tackle these extremist elements, the United States must increase its role in maintaining security in the region. Not only will this require action from the government of the US, but also NGOs, charities, private citizens, and Congressional influence are necessary to promote humanitarian aid and cooperation with civil society in the Philippines. Larger military and technical assistance will help promote maritime security and counter-terrorism on the ground. And finally, positioning as an economic power in southeast Asia will help both the US and the Philippines cut terrorist funding whilst at the same time developing a stable architecture and sphere of influence that could repel terrorist activities.