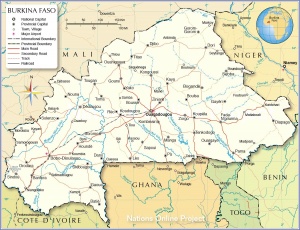

An Israeli woman carrying a coffin with family members and friends to protest domestic violence. Source: The Guardian Photographer: Jim Hollander/EPA

Throughout the world, the word “terrorism” has many different connotations; however, each definition shares certain elemtns. The conventional definition of terrorism under U.S. law is that it is “premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against noncombatant targets by subnational groups or clandestine agents.” To dissect this definition a bit further, an act of terror must meet four criteria: premeditation, political motivation, targeting of noncombatants, and violence perpetrated by a non-state actor. This definition is similar to others agreed upon by scholars studying terrorism and political violence with minor differences, and is generally the most comprehensive definition in use.

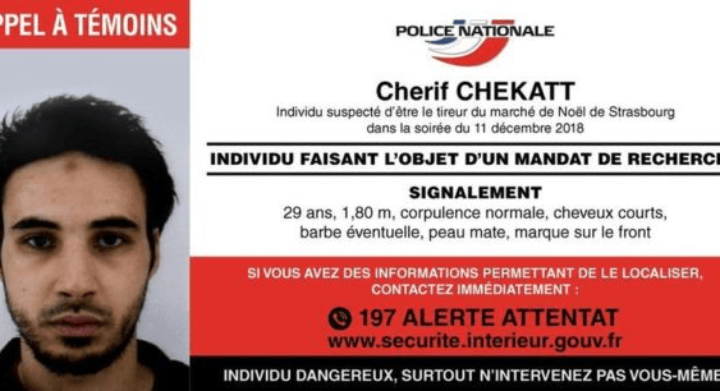

However, the interpretation of what constitutes “terrorism” is constantly undergoing change. Recently, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared that domestic violence is a form of terrorism. This declaration was made after thousands of women across Israel went on strike due to inaction by the government in curtailing the rise of domestic violence incidents within the country, arguing that domestic violence incidents have not been given priority by the Israeli government. One recent incident involved the murders of two teenage girls, both of whom were found dead on November 26, 2018. Their murders marked a total of 24 women in the state of Israel this year that have been killed by domestic violence. The objective of the strike was to increase government awareness and increase state funding to address the issue. In response to this, Netanyahu and other officials are working to pass legislation that enables the Israeli government to track domestic violence offenders via an electronic bracelet to ensure they do not violate restraining orders. By branding domestic violence as “terrorism,” Netanyahu may have aimed to mobilize political opposition to domestic violence and increase its priority level on the government’s agenda.

The case with Israel highlights one reason why the definition or interpretation of terrorism is constantly undergoing change. Often, the definition changes for political reasons. Due to an inappropriate response to the rise of domestic violence incidents, the Israeli government faced severe backlash from thousands of women, so an anti-domestic violence declaration of equal proportion was needed. To increase the scale of their response, the Israeli government declared domestic violence an act of terror, even though the common definition of domestic violence shares almost no relation to the definition of terrorism. For example, a common definition of domestic violence is violent or aggressive behavior within a home, which typically involves the abuse of a spouse or partner. This definition does not include premeditation, political motivation, the targeting of noncombatants, or a non-state actor. Ultimately, redefining domestic violence as terrorism is simply unfounded and takes away from what criminal offenses should be constituted as terrorism.

While the rise in domestic violence within Israel is of great importance and needs to be addressed properly, it has nothing to do with terrorism. Terrorism is a political instrument used by non-state actors and individuals to incite fear and reduce the legitimacy of state governments. It is separate from common criminal offenses that are committed in far greater numbers around the world. Once policy makers and government officials start using the word terrorism nonchalantly to define every heinous crime or offense, the word itself will lose its own significance and true meaning.