Image Credits: Foreign Policy illustration and Getty Images

As the US security apparatus continues to publicly focus on Iran’s expansion in the Middle East, it has done little to actively address the threat posed from Iran’s favorite proxy, Hezbollah, on the southern border. Hezbollah has been known to operate international money laundering and drug trafficking operations via Venezuela, Colombia and Mexico for years. These operations, other than, notably, the Lebanese Canadian Bank case, have most often been prosecuted as drug-related crimes, rather than crimes of terrorism.

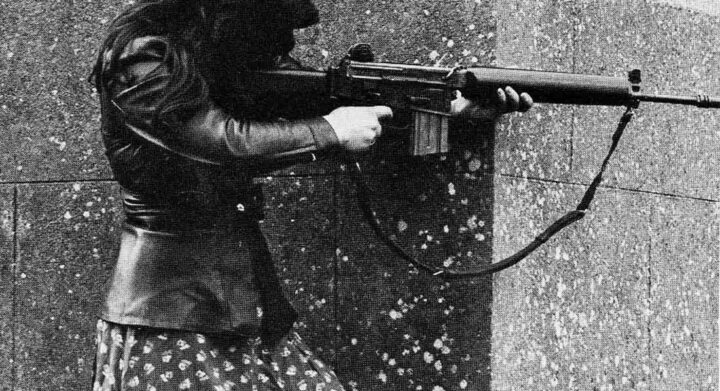

Hezbollah’s drug enterprise is not separate from its terrorist activity. Hezbollah, as directed by Iran, began engaging in the drug trade from its inception in the 1980’s, “for Satan—America and the Jews. If we cannot kill them with guns, so we will kill them with drugs.” As such, the American strategy of prosecuting drug crimes connected to Hezbollah as just that, rather than as crimes of terror shows a fundamental misunderstanding of Hezbollah’s motives.

According to a 2018 CDC study, cocaine was involved in 19.4% of drug overdose deaths in 2016— cocaine which has often made its way into the US via Hezbollah channels. In recent years, the spike in prescription drug related deaths has led the Trump administration to declare a national emergency. The opioid epidemic has at least partially driven the decline in US life expectancy, and opioid overdose victims are often found to have also taken cocaine.

The CDC study claims that in 2016 alone, more than 10,000 Americans died from drug overdoses involving cocaine; that number is more than three times the amount of Americans that died in 9/11. When you take into account the stated goal of Hezbollah to use drugs as weapons to neutralize its enemies, one wonders why the American government has yet to address this activity with the same severity as it does traditional acts of terror.

There is a law on the books that could have been used to prosecute this enterprise: the United States enacted a federal terror financing statute in 1994 after 1993’s World Trade Center bombing, under which entities can be prosecuted for knowingly providing “material support or resources” to another entity to conduct terror operations.

While money laundering can often remove the evidence needed to prosecute terror financing under the 1993 statue, the proof uncovered by the Project Cassandra task force directly ties the drug trafficking funds to Hezbollah. However, up until now, the failure to do so appears to be political, as the Obama administration allegedly did not want to engender bad faith during the Iran deal negotiations.

This has resulted in severe immediate threats to US homeland security. In May, a New York court indicted Ali Kourani, a naturalized US citizen and Hezbollah operative who allegedly attempted to identify Israeli targets in New York and obtain information on John F. Kennedy International Airport security protocols. Prior to setting up shop in New York, Kourani was previously involved with a dealership in Michigan that sold used cars to Benin; it is not unlikely this business was part of the network of used car dealerships used to launder Hezbollah’s drug profits.

Even as the United States aims to keep tensions away from its soil by announcing its intent to establish a military coalition to protect commercial shipping vessels in the waters surrounding Yemen and Iran, it leaves its doorstep unguarded by failing to take direct action against these networks.

Now that the current administration has pulled out of the deal, and is faced with rising tensions from Iran, the next move should be to go after Hezbollah’s crime-terror infrastructure under terror financing laws. Project Cassandra amassed the evidence; the Trump administration should use it to protect US citizens and put pressure on Iran.