From 2003 to May 2011, I was a prominent Jihadi propagandist, the head of a New York City based organization that set the tone, template, and methodology for radicalization and online recruitment in the West. It was the era of al-Qaeda, not ISIS. However, as the controversy continues over whether Hoda Muthana, the 24-year-old Yemeni-American who joined the so-called Islamic State and now sits in a refugee camp in North-Eastern Syria, should be returned to the United States, it seems to me that we ought to reflect on a bigger picture. We need to consider that in the Hoda Muthana situation, the true victor will be neither Donald Trump nor Abū Bakr al-Baghdadi; instead we should remember the ghost of Osama bin Laden, whose long-term strategy lives on.

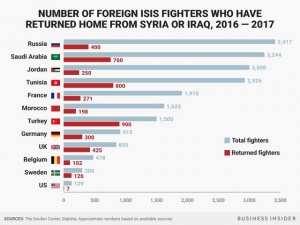

Ms. Muthana was twenty years old in 2014, when she left her Alabama home and made her way to ISIS’ self-proclaimed caliphate. As the terror group’s territorial control spread from Eastern Syria to Northern Iraq, a terrain the size of Britain, its propaganda became all the more powerful. Osama bin Laden once claimed that “everyone follows the strong horse,” and at least two hundred and fifty Americans heeded ISIS’ call.

When she first arrived in Syria, Ms. Muthana tweeted a photo of her American passport. She wrote, “Bonfire soon; no need for this!” On Memorial Day in 2015, she called for attacks in New York City. Now, like most who have survived the collapse of ISIS’ so-called caliphate, she claims that she is “deeply sorry” and wants to return. Yet, the Trump administration contends that her status as a citizen no longer applies.

Like other Western governments, it appears the Trump administration will attempt to deny the rights of those lingering in the refugee camps and prisons of northeastern Syria that should be afforded under international law. Were I still a propagandist, such a circumstance would have given me fodder for weeks. Guantanamo Bay, Bagram, and Abu Ghraib were all cornerstones of our propaganda machine. ISIS targets Western civilians simply because they are non-Muslim, at least that is what an article in their English-language magazine suggested in 2015.

I penned the lead article of the first English-language jihadi magazine in 2007. We were fighting the West, in part, because of the unequal application of the rule of law. This made it quite easy to claim that the ‘war on terror’ is actually a ‘war on Islam’. This narrative plants the seed that sprouted and went viral when Syria’s civil war became a front of bin Laden’s global insurgency. As he described it, “the freedom and democracy that you call for is for yourself.”

The controversy surrounding Ms. Muthana’s return also highlights the danger of sustained height and domestic polarization, two prongs of bin Laden’s strategic plan. In a 2004 speech directed at the American public, bin Laden explained, “All that we have to do is to send two mujahedeen to the furthest point east to raise a piece of cloth on which is written al Qaeda, in order to make generals race there to cause America to suffer human, economic and political losses without their achieving anything of note other than some benefits for their private corporations…” Does the weeklong controversy that a few women jihadis can stimulate not prove that this remains the case, that, while serious, the threat remains overblown? The only difference is that it is no longer about waging war and wasting resources abroad, but about whether spending money to bring those that traveled abroad to join the terrorists may one day lead them to wage war on us at home. These are not indicators associated with success.

Also alarming is the polarizing nature of the debate. The Trump Administration’s position largely has to do with a need to appeal to an anti-Islamic base. In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, twenty-five percent of conservatives had unfavorable views of Muslims. Today, most polling holds that rate at around sixty percent. Anti-Muslim sentiment serves a key-prong of the growing anti-establishment, right-wing sentiment that is sweeping throughout Western nations. In response, the mosqued American-Muslim community has allied with the Democratic Party. Many left-leaning legislators have supported Ms. Muthana’s return. Nevertheless, around twenty-five percent of Democrats now hold unfavorable views of Muslims, more than conservatives on 9/11. A 2016 poll conducted by the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom found that fifteen percent of Democrats thought Islam should be illegal. All of this conjoins with bin Laden’s plan of inducing collapse from within.

For certain, bin Laden would not have supported ISIS. Before he died, the godfather of global jihad had already distanced al-Qaeda from their Iraqi offshoots. And by 2014, the so-called Islamic State was brandishing supporters of al-Qaeda as apostates. In turn, al-Qaeda ideologues warned ISIS that controlling territory would prove impossible. They had already done so, unsuccessfully, in places like Somalia, Yemen, and Mali. They also warned against ISIS’ excessive zeal and wanton violence. Now, however, in the event that Ms. Muthana and others are not returned to their countries of origin, their expressions of regret will not prove a means of rejecting the notion of an Islamic State modeled on 7th Century norms. Instead, they may serve as a means of rejuvenating al-Qaeda, proving their criticism of ISIS correct. Already, pro-al-Qaeda Jihadi groups in Syria, numbering in the tens of thousands are running deradicalization camps for ISIS survivors and defectors. These jihadists would be all too happy “liberate” women like Ms. Muthana, their children, and men from the refugee camps and prisons of northeastern Syria. We might recall that ISIS itself was resurrected by way of a prison break at Camp Bucca in 2013.

These considerations are largely missing from the sensationalist debates. In a similar scenario last week, a British woman, Shamina Begun, set off a jointed firestorm in the United Kingdom when she also asked for return from the same refugee camp. In an interview, she defended her actions, but said she had not made propaganda, claiming, “I didn’t know what I was getting into when I left.” It is a common narrative. Last year, the story of a Canadian man, Abu Huzaifa, served as the focal points of a popular New York Times podcast produced by the intrepid reporter Rukmini Callimachi. Hazaifa had returned to Canada after joining ISIS and admitted to carrying out executions in Syria. Canada went into a frenzy when the government determined that they did not have enough evidence to charge him criminally. To make matters worse, it seemed that he was not remorseful. Interviewing for that podcast, I described the three fundamental beliefs jihadi propagandists used in recruitment. It was clear that Abu Huzaifa still held them, but I emphasized the need for patience. Deradicalization is a process, not an event. Often times, it is not unlike the ups and downs of recovery from addiction. Soon thereafter the controversy subsided and most moved on to the next episode. Now, however, Abu Huzaifa is doing well and an intervention program has helped him turn things around. He is deradicalizing, denouncing some of the core beliefs of jihadism in general, and is re-identifying with the value of Western norms. I remain hopeful that he will one day become a voice not unlike my own.

The world has changed a great deal since I was arrested outside a mosque in Casablanca in May of 2011. Just days after the killing of Osama bin Laden, and weeks before my colleagues Anwar al-Awlaki and Samir Khan, both American citizens, were killed in a drone strike in Yemen. Many then proclaimed the beginning of the end on the war of terror. Yet today, almost eight years later, the landscape looks like perpetual war. At home, America is torn into two black-and-white political camps. Polarization abounds. Nearly eighteen-years after September 11, 2001, we’re waging a war on violent extremism, at home and abroad.

Internationally, we are losing the ability to project liberal values. We have become an object of resentment, particularly in the Middle East. Overwhelming numbers of Arab youth now prefer the stability of authoritarianism to democracy. More Sunnis in Iraq support ISIS-style sharia law than the governance of the Iraqi state. This, of course, is music to the ears of Bashar Al-Assad, Syria, Iran, Russia and China. A new era of great-power rivalry has returned. Bin Laden’s war of attrition and policy of “bleeding to bankruptcy” does not seem an impossible feat. In fact, Osama’s son Hamza, the godfather’s prince, looks poised to wage his father’s jihad far into the future.

Yet, it is not too late. To snatch victory from the jaws of unrecognized defeat, it is time to recognize that it is no longer merely about who the Islamic terrorists are, but about who we are, as well. It is time we stop letting terrorists take us away from the principles that built the liberal world order. To start this transition, we should bring Ms. Muthana, her child, and others like them home.

Jesse Morton is a former extremist and founder of the Parallel Network.