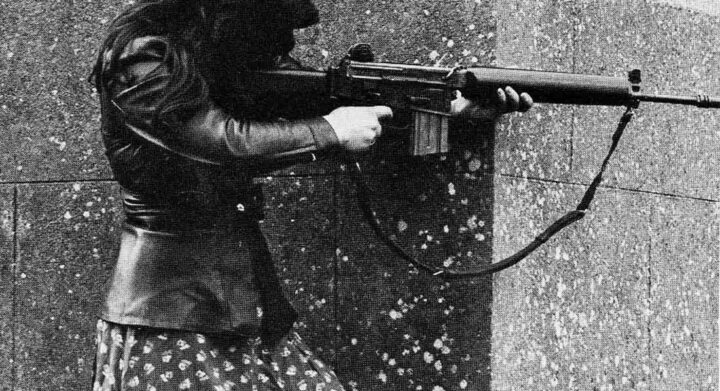

At least 27 people have been killed over the previous days in Arauca, Colombia. The authorities indicate that the deaths are due to clashes between militiamen from the National Liberation Army (ELN) and dissidents from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia’s (FARC’s) 10th Front. The situation of violence in the department of Arauca has already left several civilian victims.

The Clashes

Clashes between the two terrorist organizations began at the beginning of January. The dispute occurred in the Arauca Department, which is located on the Colombian-Venezuelan border.

While initial reports indicated that 23 people died as a result of the fight on January 6th, the Colombian Prosecutor’s Office stated that the death toll rose to 27. Likewise, it is likely that this number will continue to grow in the coming days.

Additionally, the investigations discovered that of the 21 identified bodies, 14 are Colombian while seven are Venezuelan. Thus, it is likely that both Colombians and Venezuelans comprise these criminal organizations.

Furthermore, regarding the damage caused against the civilian population, the Colombian Ombudsman’s Office pointed out that in municipalities of Arauca such as Tame, Fortul, and Saravena, 2,000 individuals are at risk of being displaced and seek to escape the armed confrontations.

The Colombian Defense Ministry indicated that among the deceased are high-ranking members of the FARC dissidents. For example, one of those identified is “Flaco Freddy,” a leader of the FARC dissidents, who had two arrest warrants, one for extortion and kidnapping and the other for illegal arms trafficking.

Some sources indicate that the conflict began due to the murder of Álvaro Padilla Tarazona, alias Mazamorro, second commander of the ELN’s Domingo Laín Sáez front, in the town of El Nula, on the border of Apure state. Colombian authorities have also revealed that many of those killed were apparently taken from their homes and shot at close range as revenge for the murder of Padilla Tarazona. However, the reasons for the confrontation stem from further back.

Historical Relationship and Rivalry Between the Two Guerrillas

The war between the ELN and the FARC has been reinvigorated with new actors. The clashes between the two guerrillas in Arauca between 2004 and 2010 left at least 500 civilians and 600 subversives dead and more than 50,000 people displaced.

Eventually, in 2010 the FARC and the ELN agreed to a truce in Arauca. The pact was known as “no more confrontation between revolutionaries” and put an end to the confrontations between the two guerrillas, and they divided the territory. In 2013, both guerrillas formally agreed to undertake a joint offensive against the Colombian Security Forces.

However, after the peace process with the FARC, several dissident groups emerged and called off the truce. The new FARC groups, especially the 10th Front, began to expand to control the regional illicit markets, such as drug trafficking and oil exploitation. Furthermore, Arauca is characterized as a strategic zone for the guerrillas due to its geographic location on the border and weak state presence.

To this day, the dispute for control of Arauca continues as the void left by the extinct FARC has not been filled and there is no clear winner for control of the region.

The State’s Response

In response to the increase in homicides and forced displacements in the Arauca Department, the Colombian Government implemented new measures. Two battalions with 680 army men have already been deployed to the Arauca Department, to strengthen security in Saravena, Arauquita, and Tame. Furthermore, checkpoints were installed on the roads of the affected municipalities, since some residents were confined to their homes for fear of clashes.

The Venezuelan Government also announced the dispatch of the military to the border. The Defense Minister of Venezuela, Vladimir Padrino López, reported that the Bolivarian National Armed Force (FANB) is deployed in the municipalities bordering Arauca.

Although it is true that the presence of the military will likely decrease the homicide rates in Arauca, a comprehensive approach is required to deal with the events that occurred in Arauca. Situations such as forced displacements require the intervention of public entities to guarantee the protection of human rights in the area.

Finally, to reduce the risk factors for sustained conflicts, it is necessary to increase the institutional supply on the border with Venezuela. Moreover, it is necessary to confront the terrorist organizations that operate there and attack their sources of financing, such as drug trafficking.

Daniel Felipe Ruiz Rozo, Counter-Terrorism Research Fellow