Greek border police shot and killed a refugee as he attempted to cross the border following Turkey’s announcement that the border is open.

Rohullah, an international student studying at Trakya University, stated, “I was there when I heard the gunshots. I saw a woman knocked to the ground. We were scared and ran away. I did not know about the Syrian refugee that was killed but I saw the women that were shot.”

Rohullah is distributing food and clothing to refugees in the border of Turkey-Greece in the province of Edirne. March 4, 2020.

He added, “My school is about a 10-minute drive from the border, and as soon as the Turkish government opened the border, refugees poured into our city on their way to the border. My classmates and I went to greet the refugees on the day that the shooting took place. All of them had crossed the Turkish border and were right in the center of the Turkish-Greek border. Some children were playing football and then suddenly, a group of refugees pushed towards the border, about 15 meters, and the Greek police began to shoot and fire tear gas.”

The victim was Ahmed Abu Emad, a Syrian refugee from Aleppo. He represents one of the thousands that have left their homeland to escape ongoing tensions and terrorism in order to have a better life. Like many before him, his journey ended before he could reach his dream. So many refugees here tell our researcher “we want to study and build a new life.” This situation is a tangible example just how conflict disrupts lives, causes immense pain and pushes the human condition to its limits.

Nearly 4500 refugees from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Iran, Iraq, Morocco, Pakistan, Palestine and Somalia are currently seeking to enter Greece. At this particular encampment, there were around 500 refugees and our researchers interviewed as well as aided them in ways that they could. “They camp in places near the river and by resources such as wood so they can make fires to keep them warm”, said Rohullah.

The Interview Project

We were able to interview one young man on his second attempt to reach a better life in Europe. Ahmad Zahir, 22, from Balkh, Afghanistan is just one of the thousands leaving with or without their families to reach Europe for a better life. Since the refugee crises of 2015, thousands of these ‘dream-chasers’ have drowned in the Aegean sea, along the Afghan-Iranian border or in perilous journeys fleeing Syria to reach Turkey. It has been a difficult endeavor full of risk, but those seeking prosperity or security consider it worthwhile to attempt.

Zahir relayed that he reached Greece on the first day that the Turkish border opened, but was arrested shortly after by the Greek border police. He paid about $25 US to get to Edirne from Istanbul.

The 22-year-old summarized his experience as: “We crossed the border on the first day, but soon we were arrested. The Greek police took our money, phones and belongings and then deported us back to Edirne with one pair of pants and a shirt. I am cold and a Turk gave me this jacket to keep me warm.” He added that, “When the Turkish government announced that the border was open, we left everything behind, but the Greek border is closed now. We cannot go back and do not know what to do.”

Why did you leave Afghanistan?

The security situation in our country is bad with an ongoing insurgency and no jobs. My family and I decided to leave for Europe mainly to live a good life and this is now my second attempt. Without money, a place to stay or live, we do not know what our destiny will be. They said the border is open, but it has been three days since we have been here.

Where do you stay?

We have no option, but to sleep here. It is not a problem for me although it is cold, but you can see children 4-5 years old, pregnant women, and older people here. These conditions are really bad for them. The weather is extremely cold as this is winter. We are lucky to be near the trees as we burn them night and day to keep us warm.

What’s your plan for going to Europe? New life? Work?

Everybody has this plan, not only me. Let’s see if the border will open or not*. At this point, we have nothing left to lose if we go back to Istanbul or anywhere else because we already lost everything we had. Let’s see what’s going to happen. Wait for the border to open and start a new life for ourselves. I want to go to school. *He means the Greek border.

Do you have plans to go back to Afghanistan?

If we have to, we might. But no plans now to go back because if we go back, there will be no jobs or life there for us.

Why Turkey opened its borders to Greece?

The reasoning is complex and percolated for years. In 2016, Turkey signed an agreement with the European Union during the 2015-16 refugee crisis to stem the flow of refugees in exchange for the allocation of funds to help the millions of refugees from war-torn countries. (Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria had the highest number of refugees.) “All our efforts contributed significantly to the security of Europe. However, our calls were ignored by the EU and member states,” said Sami Aksoy, the Turkish foreign ministry spokesman to Aljazeera.

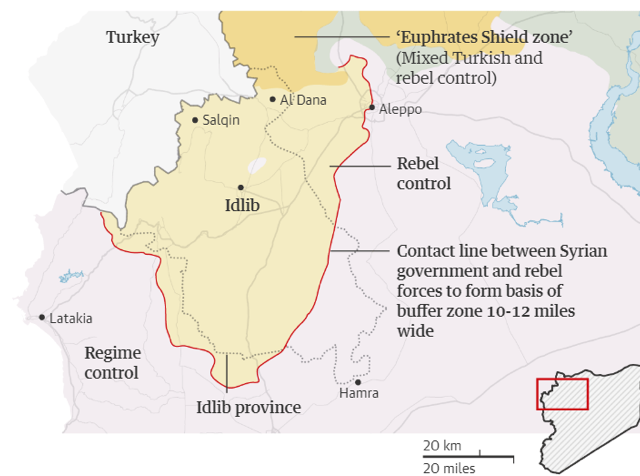

Turkey has subsequently pointed fingers and accused the EU of reneging on its 2016 promises and consequently opened its borders for refugees to cross into Europe on February 29, 2020. This decision came shortly after 35 Turkish soldiers were killed in an a Syrian regime airstrike near Idlib on February 27. Turkey’s decision to open its borders can be seen as a strategic move to gain the support of the EU in support of Turkish involvement in the ongoing Syrian war as well as remind them to implement the articles on the previous agreement.

Turkey currently hosts nearly 4.1 million refugees and asylum seekers, including 3.7 million Syrians.

How do refugees cross the Turkish border?

In 2015, when I first reported on the refugee crisis in Istanbul, Turkey was inundated with refugees from everywhere. They slept in national parks as well as beaches out of necessity and poverty. The Turkish people were generous and helped them, particularly the police. Although they came illegally to Turkey, the police did not question them unless they committed a crime.

While there, I met a human smuggler who went by the alias “Dadar.” Human smuggling is a lucrative business in Turkey and Dadar was especially prepared as he had four cell phones upon which he spent most of his time speaking with refugees. New refugees transitioned into new clients and after reaching a deal, Dadar helped them settle and provided them with food. He acted like a humanitarian aid worker, but his end goal was payment for his services.

Dadar charged refugees a fee for his services and additional charges for those traversing countries. He not only helped refugees cross the border, but also helped bring refugees from Afghanistan and Iran as well. “I enjoy doing this work because first I make good money and second I help them reach their destinations,” said Dadar.

Here are some of the fees Dadar charged the refugees for his smuggling services:

From Afghanistan to Turkey — $2000

From Turkey to Greece — $3500

From Turkey to Germany or London — $6500

On Day 3, I went to see where he kept his clients— the refugees. We drove to a place called Zeytinburnu about 25 minutes from Sultanahmet mosque. It was there I encountered many Afghans engaged in restaurants, shops and other businesses. Thousands of Syrians and Iraqis were there too. This was the place where many new refugees from Afghanistan and Syria stayed due to the proximity to resources and the low costs.

My research has often revealed that refugees and migrants typically tend to stay in communities where there are commonalities and similarities with others. For example, there are numerous cities in the United States and European countries, such as Germany, where refugees tend to settle and create communities of their own whilst engaged in their unique cultures. They adopt these urban areas as their new home.

Dadar took me to a residential apartment complex in the crowded streets of Istanbul where he kept even more of his clients. As I walked into a unit on the fifth floor, I saw 18 people — new arrivals from Afghanistan and Iran — living together in a one-bedroom apartment. Upon arrival, Dadar greeted his clients and explained all the next steps of their journey to them.

“We will inshallah leave the city in a couple of days. Please let me know if you need anything. Your food will be on time and I’m going to buy you guys vests and then hit the road towards the border,” said Dadar to the refugees.

The next day, I called Dadar and inquired about what to expect next. He told me to meet him for breakfast — Kahvalte. While enjoying the Turkish sultan style breakfast, he laid out his plans and offered to take me to the border. I agreed. After breakfast, he took me to the downtown of Zeytinburnu where he purchased 95 lifejackets. In order for him to transport the refugees, he worked with Kurdish Turks fluent in the language, familiar with police checkpoints and back routes.

Early morning the next day at 04:00, Dadar picked me up from the hotel and took me to a bus where we greeted the driver and 25 refugees. It is important to recognize that many refugees are not all young or travelling by themselves, but rather, families with children account for the largest number of refugees. I encountered a family of four from Kabul, Afghanistan. They sold their house in Kabul and entrusted their money with a dealer from there who would wire it upon their arrival in Germany — their final destination. For them to get to Germany, they had to go through one of the riskiest routes — the Aegean Sea.

Refugees departed by a bus while Dadar and I left in his Fiat. He chose a specific long route to avoid any ferries where a car loaded with refugees could be easily spotted by the police. After 5:40 hours, we reached our destination — Canakkale.

Canakkale was the main point of operation for smuggling refugees to Europe. From there, Dadar took them to the sea between trees and bushes. Kurdish and Afghan had already prepared the rafts and boats to depart. All 25 refugees were loaded on one boat and they were handed a knife with explicit instructions to cut the raft once they reached their destination. They were to leave absolutely no evidence behind for the Greek border police to notice.

Upon their arrival in Greece, some turned themselves in and then the Greek government sent them to different European nations. Germany received the most refugees at that time and this consequently compelled many others to risk the trip to enrich their lives. Out of the 25 refugees that I met and with whom I made the trip to the border, 8 of them are in Germany. Two added me as a connection on Facebook and we continue to be friends.

Nonetheless, not all stories have a happy ending. Thousands have drowned in the Aegean Sea whilst on their way to seek a better life, including the viral image of a Syrian toddler, Alan-al-Kurdi, whose body washed ashore on a Turkish beach in 2015.

Business continued for Dadar. This was a day-to-day enterprise for him and he continued until Turkey reached a deal with the EU to close its borders to refugees. He was able to turn a large amount of money he received to a successful real-estate business in Istanbul.

Should refugees leave Turkey?

Turkey has been generous in its support of refugees across the country and even gave that eligible citizenship to make a new life in the country. It has its merits. Turkey is a beautiful and safe country and attractive to Muslim refugees as it holds the historical significance as the place of the Ottoman Empire and the Sultan who conquered Europe and Africa. Further, it is a state with a respectable Gross Domestic Product (GDP), so refugees can make a living there if they truly want.

However, most refugees prefer Europe over Turkey and this is rooted in a drive for prosperity, rather than a search for security and aversion to terrorism. They choose this logistically treacherous path rather than settling in Turkey where the government has been generous towards them. Not all refugees can receive permanent residency or citizenship to remain in Turkey, however, there are ways to improve their lot. If they decide to stay and work hard, legal residency in the country is a possibility.

Authors note:

I left Turkey and tried to reach Dadar via the phone number he provided me as I wanted to do another interview project with him. The attempt was unsuccessful. His job was not easy as he regularly fought with Kurdish human smugglers as competed with rivals over prime territory that could act as points of departure for refugees. It was a war between smugglers as they fought to smuggle more refugees to make the most money.

Editorial note:

A researcher with Rise to Peace traveled to the border between Greece and Turkey at Edirne to file a report on Day 3 of the refugee attempts to cross the Turkish border following an announcement that the Turkish border is open. All photos and videos were taken by Rise to Peace with permission and right of usage by the refugees. As part of this initiative, we interviewed one of the refugees whose interview and video are featured below.

Numbers: Approximately 500 families in one area on the beach. In about 4 days, they left their jobs in different parts of Turkey and came here. They are in need of blankets and I even saw a newborn baby.

Ages: A diverse range from a newborn baby to the elderly. The average age is approximately 40 years old though there are a lot of young adults. There are many families with 2-3 children though there are some traveling in groups with as many as 7.

Refugees origins: Most come from Syria, followed by Afghanistan, then Iraq, and Somalia. Those from Bangladesh, Iran, Morocco, Nepal, Pakistan and Palestine round out the rest.

Reasons for leaving: In search of a better life, security and an escape from terrorism.

Interview: Ahmad Zahir, 22 years old from Mazar-e-Sharif, Afghanistan. This is his second time crossing the border.