Editor’s Note: Rise to Peace Research Fellows are dedicated to studying all matters of violent extremism and productive ways to contribute to the wider counter-terrorism conversation. Not only do they contribute to the organization, but at their educational institutions as well. Research Fellow Cameron Hoffman alongside his peers Heather Solomon, Daniel Pieratt and Gabriel Cirio at the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Pittsburgh (GSPIA) created a data set to study the relationship between GDP and terrorism. Cameron further expounded upon the collectively created data set to reach his own conclusions of the question at hand. The following is a short explanation of the regression tables compiled by the team and the related, independent analysis of our Research Fellow.

Few analysts disagree on the implementation of measures to reduce international terrorism, but there are multiple opinions on how to properly address the issue. For years, countries relied on counter-terrorism strategies reliant on military operations, such as airstrikes and troop deployments. Accordingly, the efficacy of decapitation strikes came into question as well.

In another area of study, academics continue to investigate the connection between poverty and economic inequality in regard to recruitment tactics of terrorist organizations. Findings have already influenced policy as governments, like the United States, include the stabilization of economies impacted by terrorism in their national security strategies.

Studies that have changed national policies indicate that the relative deprivation of individuals is a crucial factor in their recruitment to terrorist organizations. Those with social mobility and economic welfare that is frustrated — or eliminated — are at a greater risk of radicalization as terrorist organizations provide social and economic roles the status-quo does not. As a result, countries with highly educated populations that are largely unemployed or underemployed are breeding grounds for extremist ideologies and terrorist organization recruitment. Therefore, building the economies of at-risk states must play a larger part in counter-terrorism strategies.

Additionally, the impact that terrorist organizations and their attacks have on the economies of affected nations has not been extensively studied. These organizations provide economic incentives and escapes from struggling economies, but do their attacks create more economic downturn? If so, it would suggest a circular self-supporting relationship and an additional benefit to the political goals of terrorist attacks.

Using a specifically created formula, this relationship was tested. A data set — including the statistics from over 175 countries within a a 20-year period (1995-2014) — was sourced with inputs from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the World Bank for income, and the Global Terrorism Database for for terrorist attacks and their descriptive characteristics.

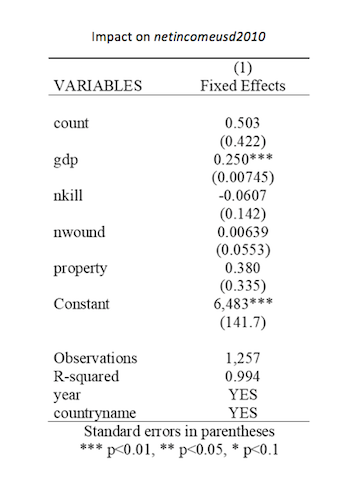

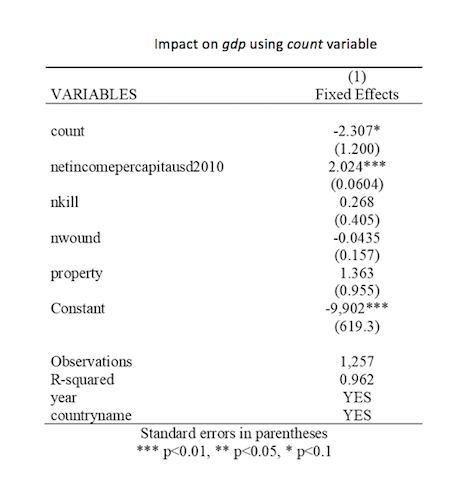

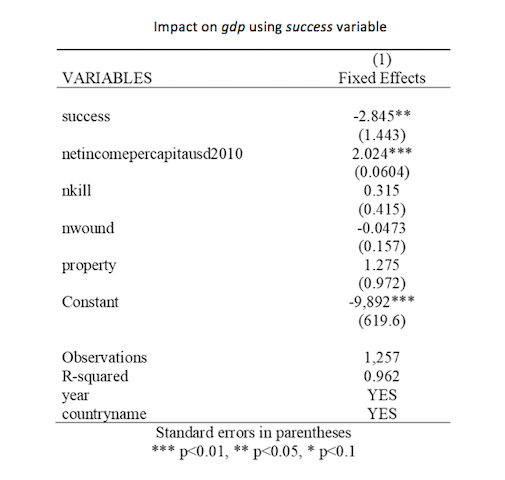

Data was based on seven variables: netincomeusd2010 (net income per capita in 2010 USD, gdp (gross domestic product per capita in 2010 USD), count (number of terrorist attacks in a country in a given year), success (the number of attacks that were successful in their aim)(1), nkill (number of people killed by terrorist attacks in a given year), nwound (the number of individuals wounded by terrorist attacks in a given year), property (value denoting the amount of property damage in 2010 USD), year (year of observation), and countryname (the name of the country from which observations are taken).

The research concluded that terrorist attacks do not statistically impact the earnings of citizens of the affected country, but they do impact the GDP of the country at the 10% level. Additionally, when testing successful terrorist attacks independently, the attacks made a larger impact on GDP at the 5% significance level. The research model, findings, and regression tables are below.

As the above table indicates, the first regression(2) output indicates no statistically significant relationships between count, nkill, nwound, property, and in relation to netincomeusd2010. The only statistically significant relationship is between gdp and netincomeusd2010. Replacing success for count did not affect the data significantly.

The second regression table(3) testing the impact on gdp produced more interesting findings. While gdp is greatly impacted by netincomeusd2010 and is significant at the 1% level, like the earlier test, the count variable impacts gdp at the 10% level(4) and success impacts gdp at the 5% level. The variables nkill and property were not significant. The results of those tests are below.

This research supports that counter-terrorism strategies must include plans to develop regions economically in a way that positively impacts the incomes of citizens. Strategies focused on the prevention of attacks by weakening terrorist organizations militarily will not affect the economic and political environments that they thrive in. A reduction of terrorist attacks may safeguard GDP, but it has no effect on the earnings of vulnerable civilians.

More research is needed to test the relationship between increased rates of terrorism and GDP. As the relationship between GDP and income is very connected, it is interesting that terrorist attacks impact GDP, but not income. Does the GDP decline because of public funds devoted to counter-terrorism, the destruction of government facilities? Does international trade to countries decline when terrorist organizations are present, such as investor fears, and other factors?

Is it possible that terrorist attacks impact the income of the populace when they decline the GDP by significant amounts? If the second is true, then military responses that limit attacks are more beneficial than previously credited. The answers to these questions will impact economic counter-terrorism strategies.

It should also be noted that because terrorism is expressly political, terrorist motives are not simply to destroy, but to achieve specific political objectives. Influence over the GDP and average income of states where they operate are not within the goals of terrorist organizations. This is important to note as efforts to build economies of targeted regions are unlikely to be thwarted by terrorist organizations. All the same, the results of this research can aid policymakers in crafting international counter-terrorism plans.

(1) Both variables cannot be included in the same regression as count includes the observations in success, which skews the data.

(2) Regression code: areg netincomepercapitausd2010 count gdp nkill nwound property i.year, a(countryname)

(3) “areg gdp success netincomepercapitausd2010 nkill nwound property i.year, a(countryname)” and “areg gdp count netincomepercapitausd2010 nkill nwound property i.year, a(countryname)”

(4) It should also be noted that as the p-value is .054 that it is nearly significant at the 5% level.

– Cameron Hoffman