It is not a new agenda for Twitter to be the ‘go to’ space for encouraging violent extremist activities, though, since America made the decision to withdraw their military troops from Afghanistan, it has been pervaded with tweets related to Afghanistan’s latest events.

The Content

Twitter has been filled with widespread opinions on the actions taken against Afghan people by the Taliban since early June. For instance, some question how they make the shocking choice to become abductors in the first place, and consider these ‘symbolic acts of bravery’: “What does it say about the fundamentals they follow?” One user queries. It seems that it is not traditional Islam they aspire to and believe in, but instead their own remodelled version of its culture that forces militarization upon vulnerable people and is then rattled by their lack of appeal.

On the other hand, the majority of users were easily identified as supporters of the Taliban through tweets and pictures that expressed their appreciation towards the group and their violent acts. One supporter quotes, “All Muslims around the world support #Taliban” which touches upon a controversial topic, but suggests that Taliban supporters online are essentially brainwashed by the Taliban-led approach to Islam. Other supporters share simple but meaningful tweets and pictures that highlight gratitude towards the Taliban and their activities to date, as evidenced below. However, all tweets are collectively managed through one specific hashtag: #TalibanOurGuardians. There were approx. 70% of content that referenced the hashtag demonstrated support towards the Taliban, whilst the remaining 30% appeared non-supportive and against the Taliban government to reform policy and livelihoods in Central Asia.

(Photograph highlights recent tweets from Taliban supporters across Twitter since June 2021 – for research purposes).

How are the Taliban described?

Since early June, the vocabulary used by Taliban supporters on Twitter was for the most part positive or in favour of the group, their governing intentions, and pleaded that their actions whilst taking over Afghanistan were feasible. Some describe the Taliban using terms that compliment them, such as heroes, intelligent, brave, our protectors and honourable economy, and ‘not terrorists’. The online support for the Taliban suggests that there is a worrying increase of group interest since their uproar against the Afghan people and justification for using violence as a way to eliminate non-believers and gain control quicker. Nevertheless, these audiences trust that the Taliban are devoted soldiers that are simply taking back their country and offer protection from democracy that is destroying their legacy; despite the evidence that draws upon links with terrorist organizations such as Al-Qaeda that assisted attacks to be carried out.

In contrast, some users directly challenge this perspective and perceive the Taliban negatively with regards to their decisions to brutally murder innocent people to gain power. One non-supporter argues how Afghan people are a ‘threat’ to the Taliban, such as Afghan comedian Khasha who was beaten and killed by Taliban members which was video streamed online. Examples of terms used by non-supporters to describe the Taliban are the enemy, animals, diabolical and fanatic idiots, and terrorists. It seems that non-supporters of the Taliban question their legitimacy as followers of Islam and regard their captures of new areas more recently as downfalls, not victories, due to the negative impact and unfortunate consequences they have caused.

Who are the Taliban supporters on Twitter?

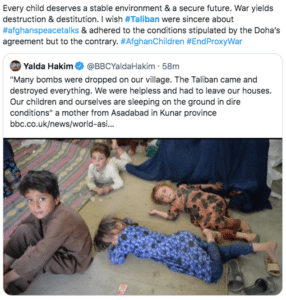

Amongst the small number of tweets that remain public, the majority of Taliban supporters were men in comparison to women and often spoke highly of having children or displayed pictures with/ of children that appear to be culturized into the group as young soldiers. For instance, one supporter argues that “Afghans are happy under Taliban control” occupied by pictures of children engaging with Taliban fighters. Does this highlight the truth in Afghanistan? Or a militant’s perspective of bringing up children (young boys) under the Taliban’s command? Similar to how research confirms that ISIL supporters online reflect behaviours of fighters offline in regards to bravery, pro-Taliban users speak of a stable environment for women and children in Afghanistan to soften its destroyed neighbourhoods, and appeal to vulnerable users. However, the reality is contradictory, which a hashtag-user outlines on Twitter:

Additionally, some content outlines the Taliban’s hatred towards journalists, judges, peace activists and women in power, which reporters describe as their targets in their new strategy. For instance, Saba Sahar documents through a Twitter video that “The Taliban can never accept that I am a policewoman” which resulted in her experiencing an assassination attempt by the Taliban. Non-believers took to Twitter to respond to her video with praise regarding bravery and the disgrace of the Taliban’s attitude towards women, despite their claims of gender equality and safety for women.

Going Forward

Looking to social media is undeniably credible for understanding the risk to Afghan people and the active beliefs of pro-Taliban users online. By using the internet as a data source to gather information on the impact and opinions of governmental decisions, we can source out areas for future development in Counter-Terrorism. This includes better disruption techniques of video content that particularly displays brutal and disturbing scenes, and of key terms or hashtags as red flags for advertising false information online that manipulates and assists radicalisation. Alongside this, we can distinguish the problems faced by Afghan communities from different areas around the globe and the perspectives on the positions of power and its consequences for governmental disputes in the future.