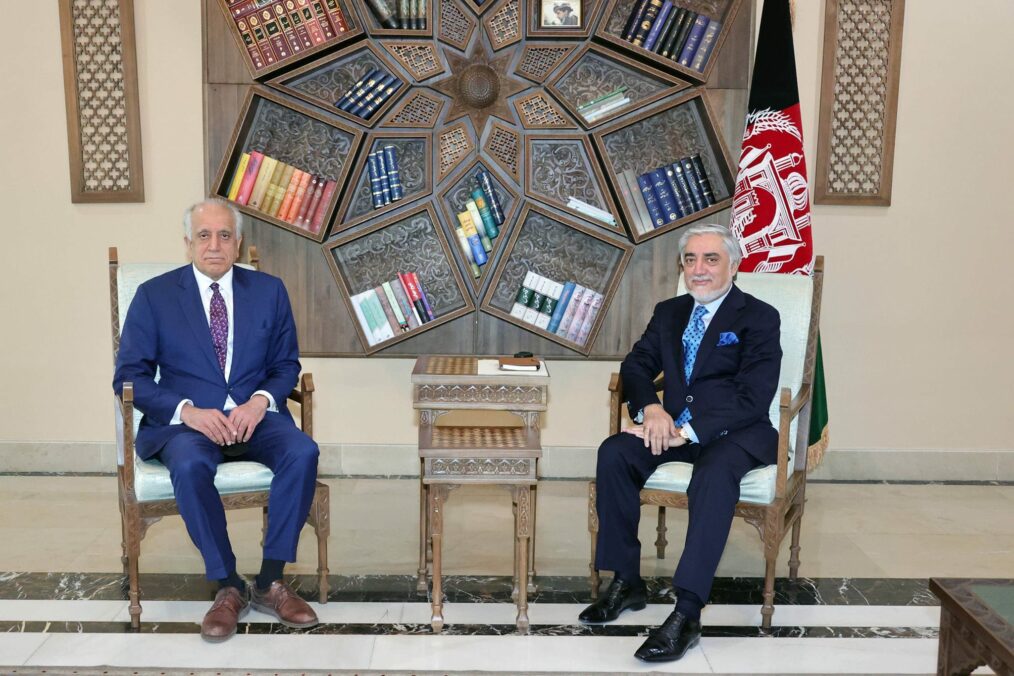

Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad, the US Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation, has left Washington DC for a trip to Kabul. His trip aims to resolve the stalemate on the Afghan Peace Process and resume the discussion with the afghan technocrats, the afghan warlords, the Mujaheddin and the Taliban representatives.

The trip comes just a few days after the anniversary of the Afghan Peace Process, which in the last year has experienced some back and forth. Many factors have affected the process including, a lack of interest from the Taliban in the process overall, a domestic rivalry to the government, and the call from the opposition parties for the current government to be dissolved and replaced by an interim government. All of these factors have posed challenges with compliance to the Afghan Peace Process.

Amid the looming deadline for the US troops to withdraw from the area, the US government has organised this trip intending to create the conditions necessary not to leave Afghanistan in chaos as it has happened with the cessation of Soviet foreign aid in 1991. All due to the concerns about the increasing violence, the uncertainty, and the stalemate between the negotiation parties.

In fact, as the US State Department has announced, the aim of Khalilzad’s trip was to resume the discussions with all parties in order to achieve “a just and durable political settlement and permanent and comprehensive cease-fire.”

The result of the trip was the request from the US envoy for an UN-hosted conference on Afghanistan in order to have a regional and international debate on the establishment of peace in the area. Eleven major international conferences concerning Afghanistan have already taken place since the insurgence of instability in the area, with the last one held in November 2020 in Geneva and the first being the one held in Bonn in 2001.

The Bonn conference took place with the aim of re-creating the State of Afghanistan and defining a plan for governing the country following the U.S. invasion in response to 9/11 terrorist attacks. The agreement sought to establish a government with a strong, centralised power, a new constitution and an independent judiciary. But also to hold free and fair elections, a centralised security sector, and the protection of rights of women and also minorities, such as religious and ethnic groups.

One common critique on the Bonn conference is the exclusion of the Taliban from the negotiations, to which Brahimi refers as Bonn’s “original sin,”. The next conference would be a Bonn-style meeting, where to discuss at the international level the prospect of a participatory government, but that this time it would include the Taliban in the debate.

As Shahzada Massoud, a close aide to former president Hamid Karzai, has said: “A grand international conference that will be similar to the Bonn Conference will be held, in which the Taliban and the republic side will participate at the leadership level. At the same time, the international community, including the United States and the regional countries, will reach a political agreement that will take its legitimacy from the international community,”.

The strength of setting up international conferences lies in the ability to involve international actors and regional actors, like Pakistan and Iran. The conference lays the groundwork for multilateral discussions and negotiations between parties, encouraging Afghanistan’s neighbours and international actors to support the end of violence and to create stability in the area. The involvement of international and regional actors is pivotal for the creation of peace in Afghanistan. Pressure from the US on the Taliban to cease violence and on state response to terrorism, as well as Pakistan cooperation, are determinants of the future of Afghanistan.

Photo Credit: Afghan foreign ministry