Investment in Prisons as a Counterterrorism Approach

At a time when Europe is undergoing a new wave of terrorist attacks, the challenges posed by prisons and the monitoring of ISIL prisoners should be a focus in the fight against terrorism.

Prisons are places where inmates may be vulnerable, in contact with extremist ideas, and subject to recruitment. There the creation of networks between skilled criminals and radicalized detainees is facilitated. But prisons also face new challenges as the number and the diversity of profiles of radicalized detainees are increasing. And although they serve very different sentences, they are mainly of short duration, which poses a threat to Europe as many of them will soon be released. To reduce this threat, governments should invest in the prison system, even if it is not popular.

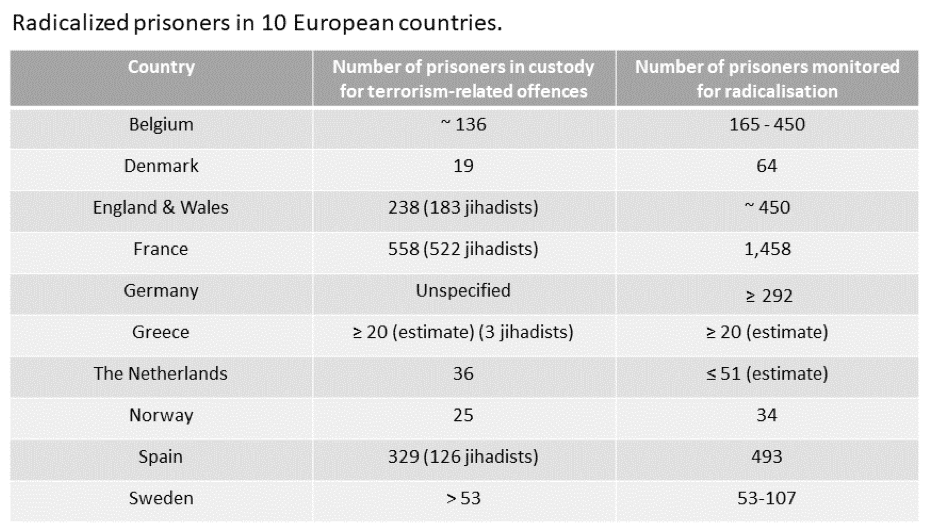

All these challenges regarding radicalized detainees were highlighted in a report published in July 2020 by the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation (ICSR). At the time of its release and amongst the ten European countries they surveyed, 54% of detainees who showed signs of radicalization were convicted for “regular” crimes. And 82% of all extremist inmates categorized by ideology were jihadists. According to Europol, it is indeed the terrorist affiliation that counted the most arrests in Europe between 2015 and 2019.

Source: Basra, Rajan, and Peter R. Neumann. “Prisons and Terrorism: Extremist Offender Management in 10 European Countries”, International Centre for the Study of Radicalization (ICSR), July 22, 2020, pp. 7-8.

The ICSR report indicates as well that the repatriation of European ISIL fighters – due to the loss of the territory of the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq – is an element that could impact radicalization in prison. The danger with their incarceration is that they may influence others and create more radicalization within the prisons, which could aggravate this problem even further.

Radicalization in prison is true all the more worrisome since some of the terrorists who have carried out attacks in Europe have been radicalized or have had contact with affiliations in prison. A case that illustrates this is the shooting at Charlie Hebdo and the siege of the Hyper Cacher in Paris, which took place in January 2015. Two of the assailants, Chérif Kouachi and Amedy Coulibali, met at the Fleury-Merogis prison, the largest prison in Europe. There, they met Djamel Beghal, who trained in Al-Qaeda camps and who became their mentor.

This case, which is back in the news with its trial, shows that the prison system has failed to prevent radicalization. Currently, most of the countries have adopted a mixed approach in their prison regimes to prevent extremism, which means that the most dangerous inmates are separated while the others are dispersed among the prison population. But even separated, dangerous detainees are not totally prevented from interacting with others or taking action.

Another challenge is the imminent release of hundreds of radicalized prisoners due to the fact that most of them have received short sentences. According to Europol, the average length of prison sentences for terrorist offenses in Europe was six years in 2019. Because some prisoners strengthened their beliefs and commitment to their extremist ideas in prison, they emerged much more dangerous than before. The challenge then is to reintegrate them into society in the best possible way.

With the exception of a minority, the terrorist attacks linked to prison since 2015 in the countries surveyed in the ICSR report have generally occurred between four months and two years after the release of the offenders. To take a current example, Kujtim Fejzulai, the perpetrator of the attack in Vienna on November 2, 2020, was released from prison 11 months earlier, in December 2019.

The rate of recidivism is low, but a characteristic of terrorism is that the impact of attacks is disproportionate to the resources and people involved. This rate is also not representative of reality and could be undervalued because some die in their attack or go abroad and do not return to prison.

In order to reduce radicalization in prisons, governments should take what may be unpopular but necessary decisions by investing in prisons. According to Rajan and Neumann, the ICSR report’s authors, they must ensure that prisons are neither overcrowded nor understaffed to ensure their security and control. Prison staff should also be trained to develop expertise that would help them notably to differentiate radicalized behavior and prisoners who just practice their faith.

Moreover, governments should encourage the sharing of information between the different services involved in the prison system and the fight against terrorism. Failure to communicate is recurrent and can lead to the release of radicalized prisoners who commit attacks. Also, extremism assessment tools should be frequently evaluated with a prison staff trained in their use and provided with the resources to implement them. And defining what “success” means is important to evaluate the results.

Prison regimes should be evaluated as well and readjusted to the behaviors and characteristics of specific offender groups. In addition, probation should be linked to prison and be seen as a stage of the same process and governments should adapt proactively their procedures and processes to changes in reality.

Last but not least, treating radicalized prisoners with respect and fairness should be the norm. Extremist ideologies rely on tales of humiliation and representations of their enemies. This game should not be played rather there should be a focus on fundamental values such as human rights and the rule of law.

Radicalization in prisons is not a new phenomena but it is currently reaching high levels. The prison population is changing and includes more radicalized inmates with more diverse profiles who serve different but often short sentences. While the repatriation of European ISIL fighters could aggravate radicalization in prison, the imminent release of radicalized prisoners worries European countries and that is why prisons should be at the center of the authorities’ concerns in their fight against terrorism. Investing in prisons may be unpopular but it is necessary.