The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a paramilitary organization that has operated out of Ireland since 1917. There have been many versions of the IRA throughout time such as the ‘OLD IRA’ and the ‘REAL IRA’ however the focus of the group has mostly remained the same, which is that the whole of Ireland should be an independent republic free from British rule.

The focus of the group has mostly remained the same, which is that the whole of Ireland should be an independent republic free from British rule.

In 1969, the IRA was determined to see the British withdrawal from Northern Ireland but with a differing of opinion, the IRA split into two separate wings: officials and provisionals. Officials used their efforts to gain independence through peaceful action, while the provisionals used violence and extremism to make its agenda known.

This division on part of the provisionals resulted in an estimated 1,800 deaths, which included more than 500 civilians. As the Provisional IRA and other paramilitary organizations continued on what can only be described as a violent path, the British Army in the meantime retaliated which eventually marked the time known as the “Troubles” which affected Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland for almost 30 years.

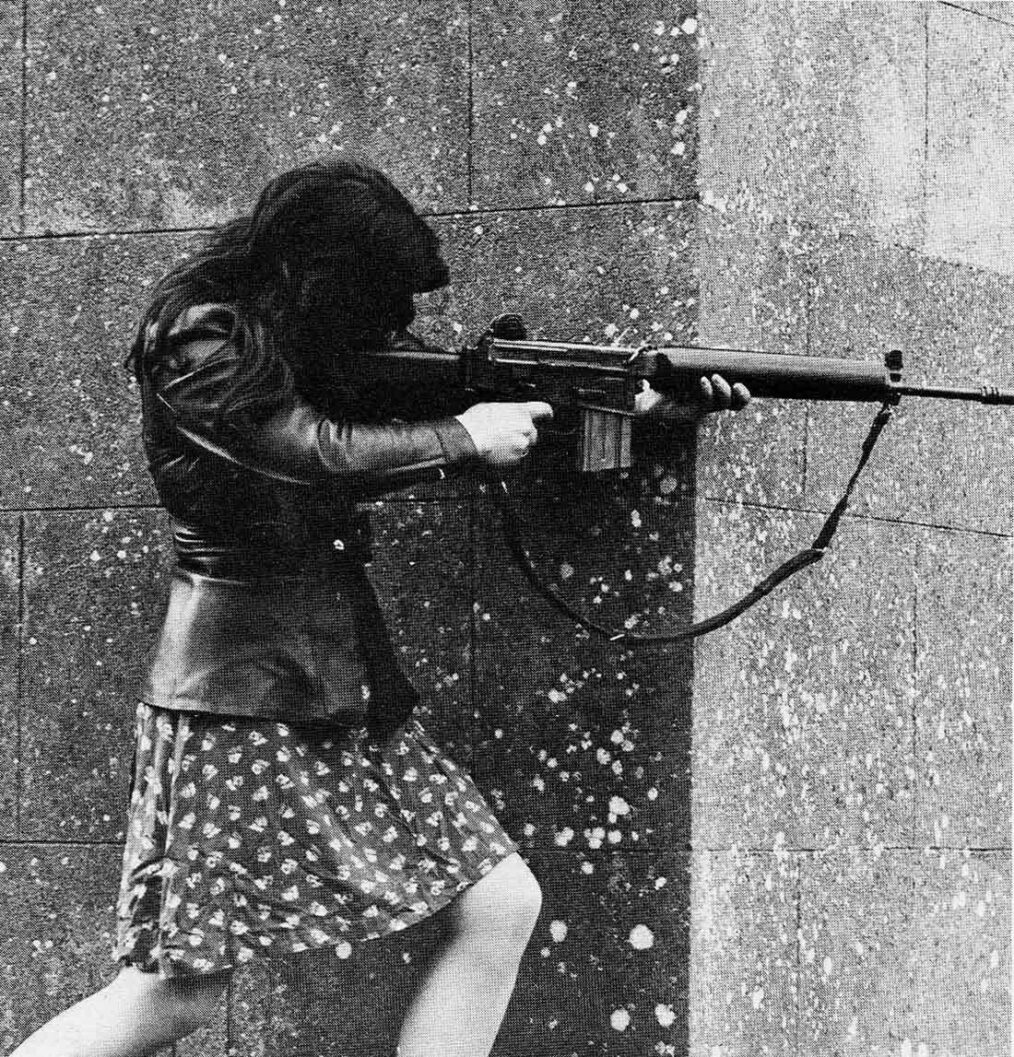

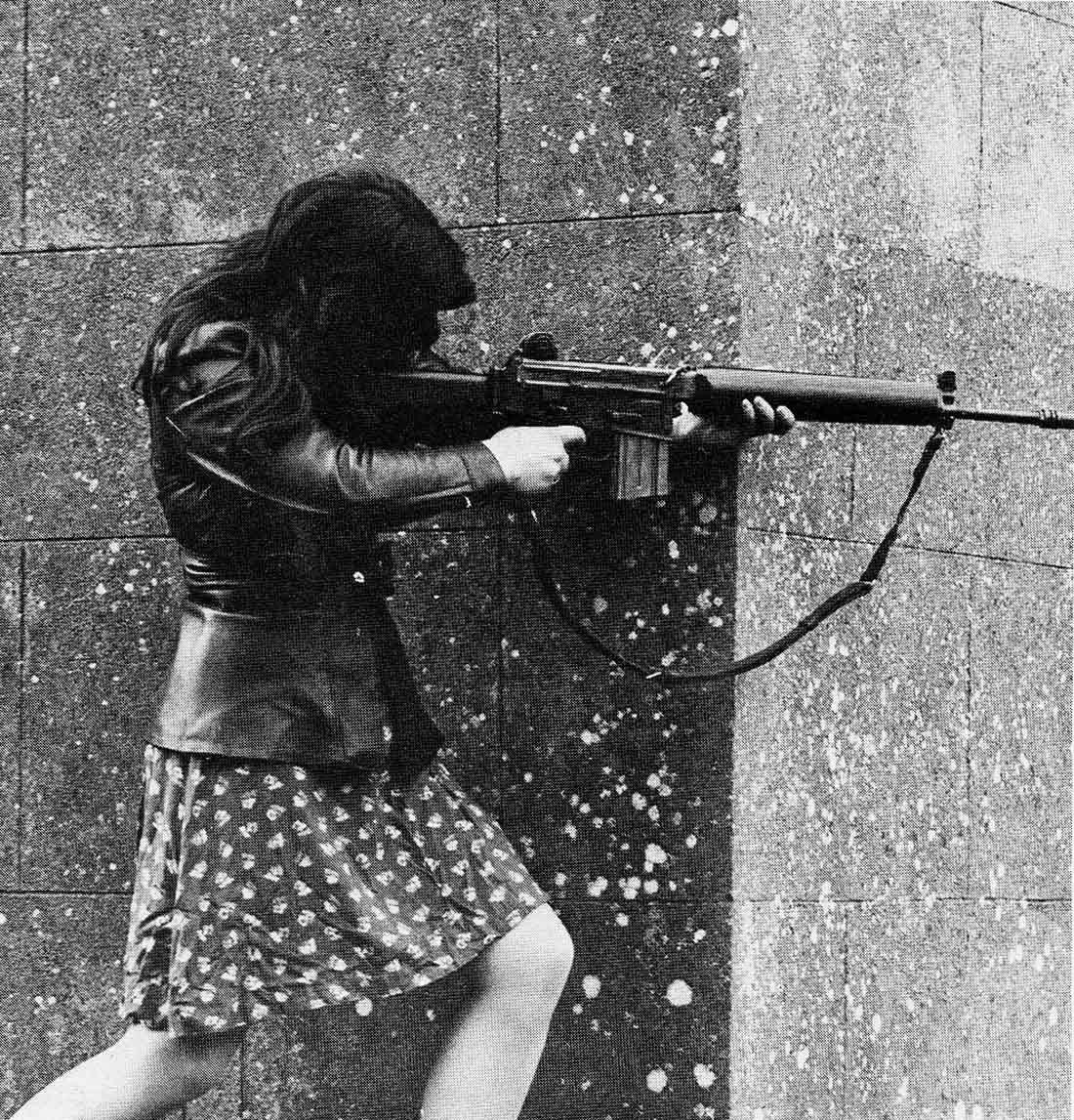

Women have been known to participate in many roles within the IRA. During the 1970s many women were compelled to join in some capacity as the resistance within the community helped to politicize them.

While many of these roles have involved protests and civil rights matters a number of women became known for their roles as combatants during the time of the troubles. This is an interesting development in paramilitary organizations as women were not often included in these physically violent positions.

The IRA stands as a departure in the traditional roles women hold in terrorism and changes the narrative of how they are viewed. This shift in the structure of terrorist groups raises the question of why the change in dynamics and what does it mean for how the group operates.

Does the addition of women to the group make it stronger or vulnerable? There is a tendency in research and in situations where female terrorists are actively observed to view them as victims instead of perpetrators despite overwhelming evidence to suggest otherwise.

There is a tendency in research and in situations where female terrorists are actively observed to view them as victims instead of perpetrators despite overwhelming evidence to suggest otherwise.

Societal norms and constructs have added to a preconceived notion that women are naturally more peaceful and less violent than men but it is naïve to allow this belief to distort the reality that women are active players in terrorism and are not to be overlooked. In fact, it could be argued that they are more dangerous than men in the sense they can use their femininity and this false image to mislead and conceal their violent agendas from others. A key member of the IRA and a prime example of this shift in gendered terrorism is Dolores Price.

In fact, it could be argued that they [women] are more dangerous than men in the sense they can use their femininity and this false image to mislead and conceal their violent agendas from others.

Dolores Price joined the Provisional IRA in the 1970s along with her sister Marian Price. During her time in the IRA, Price was known for her extreme devotion to the cause and her inherently violent nature.

Price was involved with some of the IRA’s most devastating crimes: In 1973 she participated in a car bombing at the Old Bailey in London injuring over 200 people and killing one.

Price and her sister were arrested shortly after the bombing. Originally the sentence was life imprisonment, however, their sentences were eventually brought down to 20 years. Price only served seven years for her role and participation in the bombing. While in prison Price went on a hunger strike in order to be moved to a different prison in Northern Ireland.

Other members of the IRA imprisoned for the bombing joined the hunger strike and it went on for 208 days due to the prisoners being fed forcefully by prison officers in order to keep them alive. The force-feeding was abruptly brought to an end when another member of the strike died.

Price began to resent and blame Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams for the ordering of the abduction and murder of the most high profile victim of the IRA. Price revealed that she was given the order of taking Jean McConville- a mother to 10 children, across the border where she was heinously murdered and buried by the IRA.

Price also made the accusation that Adams was responsible for the creation of a covert unit in Belfast that was used to push out informants of the IRA who were supplying information to defense agencies. Adams, who helped shape the Northern Ireland peace process, denies any knowledge of such. Price continued to be involved with political issues up until the 1990s.

Price also noted that she and her sister were fearful due to threats from other members of the IRA and the political party Sinn Féin after she made allegations against them publicly. Price died in January 2013 after being found in her home in Dublin from a suspected toxic illness due to mixing the medication.

Dolores Price’s role in the IRA raises the issue that is central to the women in extremism program- what motivates a woman to become involved in a terrorist organization and what it looks like compared to the experience of a man.

There is a certain attractiveness for men to join a terrorist organization in terms of the sexualization and allure of violence but there is little to suggest that women do not join for the same reasons.

In this case, we can only theorize about why Price joined the IRA but a lot can be deduced from her actions and involvement.

In an effort to understand more about the motivations of women in terrorist organizations there is a need to explore the attraction of power and loyalty to men in the community as factors for involvement.

Power and attraction are some of the most common reasons for the justification of violence.

Dolores Prices involvement in the IRA should pose as a reminder that combatant women can have a bigger influence in terrorism than men and should not be expected to be less militant or less dangerous due to their gender.