© CNN Money[1]

In 2015, ISIL’s annual revenue was estimated to range from $1 billion to $2.4 Billion.[2] The terror organization had a higher GDP than 60 legitimate countries. Unsurprisingly, ISIL is considered the most well-funded terrorist organization in the world.[3] Governments and law enforcement agencies must aggressively follow the money and stop the flow of financial support to reduce and ultimately eliminate terrorist conduct.

Although political and religious ideologies are often foremost in our analyses, money is primary to any terrorist attack, be it a small-scale, stand-alone attack or a large, complex operation. Terrorism operations are not always cheap. The price of an attack can range from $500, in the case of the Boston Marathon bombings, to $450,000, al Qaeda’s estimated costs for perpetrating 9/11.[4]

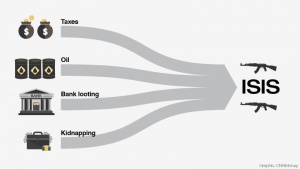

Terror groups leverage a catalog of methods to acquire funding. In many senses, ISIL is not doing anything new. Rather, it has succeeded in acquiring funding on a heretofore unprecedented scale for a terror organization. It continues to use traditional terrorist methods in addition to developing its own, unique means to acquire funding.

Terrorist groups exploit natural and economic resources. They operate in the vacuum created by weak and collapsed states. ISIL levied punishing taxes in territory it usurped. Terror groups are also perfectly situated to capitalize on unguarded reserves of diamonds and oil. Diamonds, in particular, are uniquely valuable and easy to smuggle. Al Qaeda reportedly traded in diamonds prior to 9/11.[5]

Oil, as is frequently the case, is the big-ticket item. Oil is the one resource that the current globalized economy cannot live without. The Middle East is rich in this precious fuel including ISIL territory in Syria and Iraq. Regardless of their lack of access to global oil markets, ISIL continues to find buyers for their black gold. ISIL allegedly made more than half of its 2015 revenue, roughly $500 million, through the sale of oil in its territory.[6]

Tried-and-true criminal operations remain at terrorists’ disposal. A mainstay of terrorist funding comes from the drug trade. The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE or Tamil Tigers) relied on narcotics trafficking, the Colombian FARC exploited the cocaine trade, and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) sought to drive out competing drug networks.[7] Ideologically, terrorists might denounce drug use as un-Islamic, but they never fail to exploit this revenue stream.

Kidnappings and ransoms remain a lucrative source of terrorism funding. Unlike the United States, Israel, and several European nations who refuse to pay ransoms, others have submitted to kidnapper’s demands. ISIL is estimated to have made between $20 to $45 million in kidnapping ransoms.[8] Kidnappings remain a mainstay of terrorist networks across the world.

Illegal second-hand markets exist as alternative avenues for illicit revenue. The Provisional Irish Republican Army engaged in arms smuggling throughout its terror reign. Hezbollah even exploited regional price differences in the United States to buy cigarettes in lower taxed states and illegally sell them at a discount in high tax states like New York. ISIL’s variation on the theme sees them plundering historical sites and selling priceless artifacts for millions of dollars.

State and non-state actors alike can provide economic support to terror networks. Before 9/11, state-sponsored terrorism was a significant concern. Libya, Iran, and Pakistan are perennially accused of funneling money to terrorist groups. Regional support is another key asset. Charities and corporations can serve as fronts to give an organization’s fiscal acquisitions a legal veneer[9]. Al Qaeda does this routinely. Since 9/11, though such criminal conduct has worsened, international condemnation and penalties have moved some state actors to chasten their public relations with terror groups.

Governments and law enforcement alike are familiar with terror organizations’ funding methods. However, shutting down the revenue flow is no simple task. Counter-terrorism forces do not have an easy time targeting natural resources such as captured oil fields without damaging assets that are invaluable to the state. Furthermore, how many generations of law enforcement have sought in vain to eliminate smuggling and drug trafficking? The needle hasn’t moved enough towards a cessation.

Terrorists will innovate. They will use any means available to acquire funding. Law enforcement must be equally innovative, vigilant and nimble when it comes to eliminating these networks as they appear. Law enforcement coordination has improved since 9/11, but a lack of interagency synergy continues to impede our ability to sufficiently reduce terror funding streams. Synergy requires cooperation between all agencies monitoring illicit revenue flows, be they drug enforcement, intelligence groups, or government trade organizations.

The formidable nature of the challenge before us can be discouraging. But our commitment to shutting down illicit terrorist funding is requisite in this fight. If law enforcement could slow or prevent even one attack, the effort would have been worth it. Governments, in coordination with financial institutions, must implement tighter regulations to monitor illicit capital flows and aggressively continue to shut down lucrative criminal activities.

Sources:

[1] Pagliery, Jose. “Inside the $2 Billion ISIS War Machine.” CNNMoney, last modified -12-06T03:04:34, accessed Mar 21, 2018, http://money.cnn.com/2015/12/06/news/isis-funding/index.html.

[2] Daniel L. Glaser, testimony before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Terrorism, Nonproliferation, and Trade and House Committee on Armed Services Subcommittee on Emerging Threats and Capabilities, June 9, 2016b; Center for the Analysis of Terrorism, ISIS Financing 2015, Paris, May 2016.

[3] Nicholas Ryder (2018) Out with the Old and In with the Old? A Critical Review of the Financial War on Terrorism on the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 41:2, 79-95, DOI: 10.1080/1057610X.2016.1249780

[4] Nicholas Ryder, Out with the Old and In with the Old? A Critical Review of the Financial War on Terrorism on the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant, 80-81.

[5] Terrorist Financing: U.S. Agencies should Systematically Assess Terrorists’ use of Alternative Financing Mechanisms: United States. General Accounting Office,2003.

[6] Maruyama, Ellie and Hallahan, Kelsey, “Following the Money: A Primer on Terrorist Financing,” Center for a New American Security, last modified June 9, accessed Mar 16, 2018, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/following-the-money-1.

[7] Clarke, Colin P., “Drugs & Thugs: Funding Terrorism through Narcotics Trafficking.” Journal of Strategic Security 9, no. 3

(2016): 1-15. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.9.3.1536

[8] Clarke, Colin P., Kimberly Jackson, Patrick B. Johnston, Eric Robinson, and Howard J. Shatz. Financial Futures of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant: Findings from a RAND Corporation Workshop. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2017. https://www.rand.org/pubs/conf_proceedings/CF361.html. Also available in print form.

[9] Michael Jacobson (2010) Terrorist Financing and the Internet, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 33:4, 353-363, DOI: 10.1080/10576101003587184

© Getty Images- Serial-bomber Mark Anthony Conditt, 23, left two dead and four injured after a series of attacks in Austin, Texas

© Getty Images- Serial-bomber Mark Anthony Conditt, 23, left two dead and four injured after a series of attacks in Austin, Texas